Shin is about a person willing something to be as they had imagined it would be.

Sō is about sharing that creation with other elements of the natural world.

Shin is about human mastery over the world.

Sō is about seeing humans as an integral but small part of that world.

Understanding the fundamental Japanese aesthetics of shin and sō

Tsukiyama teizō den is the name of an illustrated gardening treatise published in 1735 by Kitamura Enkin. The title translates literally as Teachings on the Making of Built Landscapes and Gardens. Nearly a hundred years later, in 1828, Akizato Ritō published a follow-up treatise, Tsukiyama teizō den kōhen ( kōhen means sequel).

In this second volume, Akizato introduces the idea of a tripart system of categorizing gardens into Formal, Semi-formal, and Informal styles. The term he used for this, shin gyō sō, was borrowed from the culture of the tea ceremony, which uses that same tri-tier system to categorize everything from tea trays to flower arrangements.

This reminds me of the way some Japanese restaurants rank meal selections as shō chiku bai, pine bamboo plum, in which pine is the most elaborate and expensive choice, and the other two follow, becoming simpler and less expensive. By the time Akizato published his sequel, shin gyō sō had become just like shō chiku bai, in the sense that it was a stereotypical way to arrange and package a complex culture in order to make it more accessible and, as always seems to happen in the long arc of cultural development, more marketable.

This was not always so. The culture of drinking tea as an art form is known by the hyper-understated moniker chanoyu, “hot water for tea.” When chanoyu was first being breathed into life by creative types back at the end of the fifteenth century, in cities like Sakai and Kyōto, what they were interested in was just the twinned aspects of shin and sō.

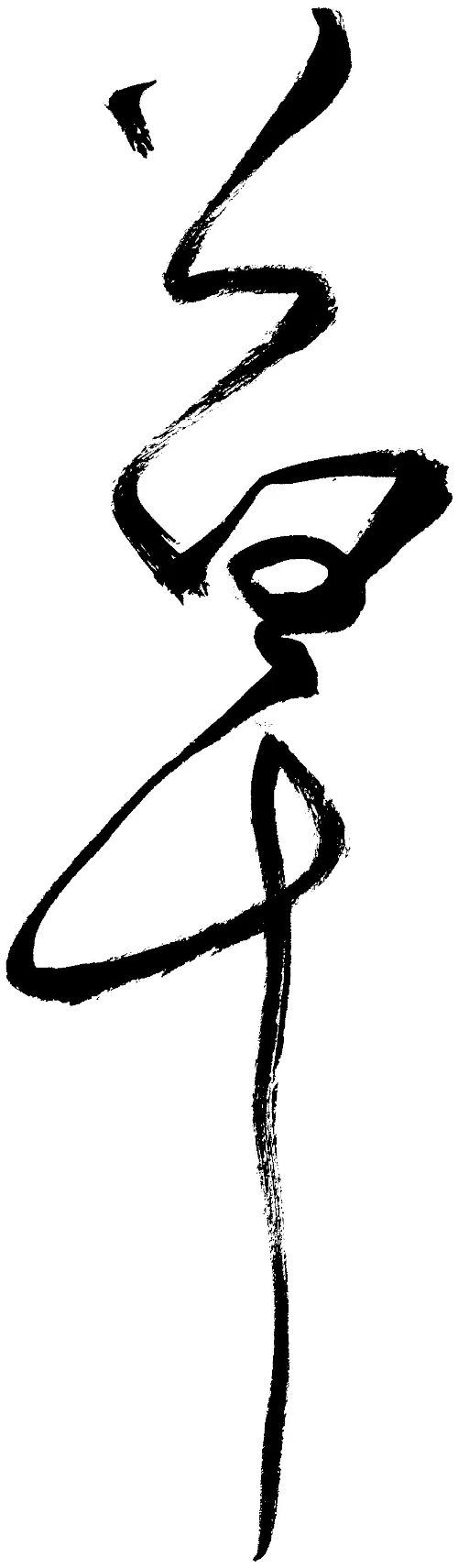

Shin is written with the character for truth 真 and sō with the character for grass 草, but don’t let that confuse you. Shin and sō are not describing truth and grasses. They are labels for two aesthetics that would come to underly chanoyu culture and, later, to permeate all of Japanese culture.

Getting back to history, the early development of chanoyu begins with the importation of an already highly-developed culture of tea drinking from China. The practice as it was imported was formal, and the accouterments and utensils used, whether a brass flower vase, a porcelain tea bowl, or a lacquered display shelf, were finely finished goods.

At the end of the fifteenth century, and through the sixteenth, the practice of tea in Japan was re-designed by a number of creative people. The Nanbōroku, a record of tea culture from the end of the seventeenth century, mentions a man named Murata Shukō (also, Jukō) who lived at the end of the fifteenth century. It describes his teahouse as having been built in the shin style and depicts it as a formal building, almost like a little chapel, with white-papered walls and a curved hip roof that was commonly used for small halls in Buddhist temples.

Whereas his own teahouse had been built in the formal shin style, Shukō was in fact an early proponent of incorporating into chanoyu new and different elements that were of Japanese origin, elements that were more natural, organic, serendipitous, and spontaneous. This was proposed by Shukō as a counterpoint to the formality of Chinese culture.

In a letter to a provincial lord who was an avid practitioner of chanoyu himself, a short note that has become known as The Letter of the Heart, Shukō writes, “Critical above all else in this way is the dissolution of the boundary line between Japanese things and Chinese things.”

Under his influence, and that of other tea masters who followed during the sixteenth century, the practice of chanoyu began to shift away from that imported Chinese formality toward a uniquely Japanese mode of tea culture in which tea gatherings employed “imperfectly natural” utensils and were held in simpler, rustic teahouses known as sōan. And there we have it, from Shukō’s shin-style teahouse to the later sō-style teahouses—the initial referencing of shin and sō.

“For me, the interesting thing here lies in the spiritual stance of shin and sō.”

What are these twinned yet polar aesthetics of shin and sō referring to? What is the driving force behind each of them? It’s elegantly simple really and, at the same time, completely fundamental to Japanese culture as it would develop through the Edo period and beyond.

Shin is the aesthetic of human control, while sō is the aesthetic of natural complexity. When a person in the process of creation has an exact idea of what they want to make—precisely what the size, shape, color, texture, finish, and so on shall be—and bring all their physical and sensory skills to bear to accomplish that, the object created is in the shin mode.

When making a woven tray, for instance, they will decide that the bamboo will be split to a width of two bu (about one-quarter inch) and sliced down until only the outer skin remains, then woven in a precise double-layered, hexagonal pattern known as nijū mutsume. They imagine this, will it to be so, then make it so. That is the spirit of shin. Complete control.

When, however, a person in the process of creation understands that they are offering only a partial guiding hand and that the preexisting nature of the materials they are using and the natural proclivities of the creative process also play a large role in forming the object to be, that thing will end up in the sō mode.

If making a tea bowl, they will form the clay loosely into a bowl shape by pinching it with their fingers, cast a glaze across it almost haphazardly, then leave the rest up to the kiln gods, stepping back from the process to allow those other entities to bend and warp the work with their heat and coat it with a complex finish of melting ash. That is the spirit of sō.

Shin is about a person willing something to be as they had imagined it would be.

Sō is about sharing that creation with other elements of the natural world.

Shin is about acquiring complete control over the creative process.

Sō is about relinquishing that control.

Shin is about human mastery over the world.

Sō is about seeing humans as an integral but small part of that world.

If there are porcelain ceramics created in a wholly symmetrical way, with delicately brushed paintings on the glistening surface, the whole an ode to perfection, then there are also wood-fired ceramics made of gritty clay that crack and slump in the heat of the kiln and acquire a glaze from the natural process of burning wood that no human hand could ever replicate.

If lacquer can be applied in multiple layers, each one polished before receiving the next so that the completed black surface is akin to a dark mirror, then there is also a basket of woven bamboo covered with a gnarly dark lacquer that looks like nothing so much as the sediment of a hundred years of soot.

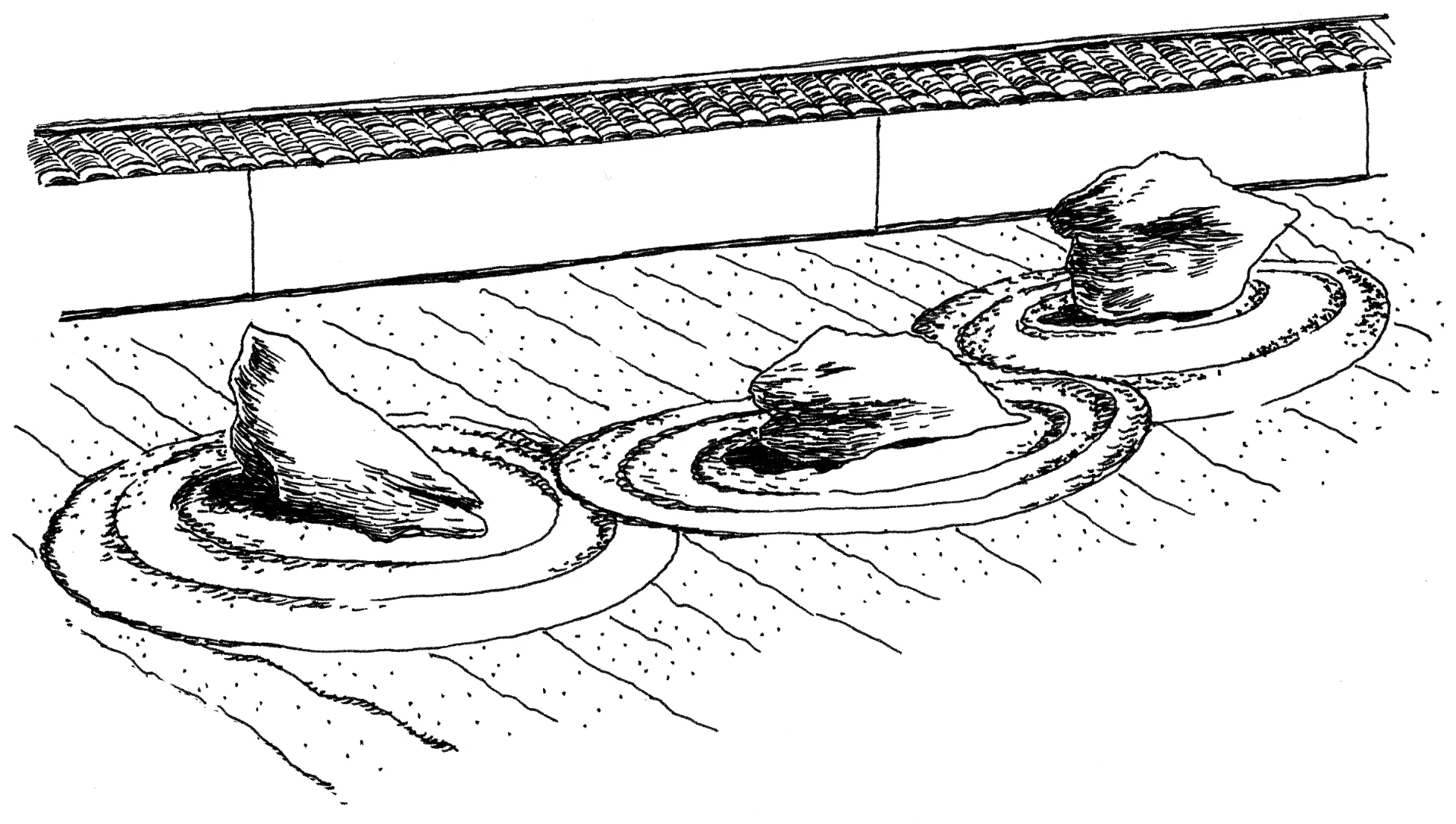

If temple halls are made from massive posts and beams of wood that have been cut and planed to precise dimensions and lifted up into a cathedral of axial symmetry, then there are teahouses made of slender natural timbers, some still with the bark on them as if just moments before they had been growing in the nearby forest, the whole laid out in an entirely situational manner.

If flowers and branches can be gathered into complex arrangements that follow age-old rules of balance and construction, so can a single bloom be gentled into a vase, artlessly capturing the essence of a season.

Of course, the world is not black and white. If there are objects that seem to be squarely expressing the essence of shin or sō exclusively, so too are there those that have some quality of each. Thus the appearance of the third member of the club, the gyō aesthetic that is a medium between its more rigorous siblings, or a combination of both of them.

But for me, the interesting thing here lies in the spiritual stance of shin and sō. As a designer, as a creator, which are you? Do you lean into the world hard, set your hand upon it and lay down the law of how things shall be? Or, do you enter into a kind of primordial dance with the world, nudging here and there, suggesting this or that, then sit back to watch what the world will make of what you began?

Marc Peter Keane

Kyoto, Japan

Marc Peter Keane is an American landscape architect, artist and writer living in Kyoto, Japan. He specializes in Japanese garden design, where he artfully blends Eastern and Western aesthetics and philosophies. He has designed and built numerous gardens for private residences, businesses and temples both in Japan and abroad.

He is the author of several non-fiction and fiction books including Japanese Garden Design, The Art of Setting Stones, Dear Cloud, and Of Arcs and Circles.

Text of The Bipolar Twins of Japanese Art was originally published in Of Arcs and Circles by Marc Peter Keane, © 2022 Marc Peter Keane, used by permission of Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, California.

Objects used to illustrate the essay are from the private collection of Musubi Academy founder, Laurens van Aarle. Makers in order of appearance: Hataman Touen (fig plate), Yoji Yamada (rustic plate), Noritake (iris cup), unknown (Bizen cup), unknown (bamboo tea whisk), Hosai Matsubayashi XVI (chawan), Nick Lamb (rabbit netsuke), Sawada Hideo (wooden sculpture), Hosai Matsubayashi XVI (chawan), Time & Style (lacquer bowl), Yu Uchida (wooden plate), Maya Matsuhisa (kirikane incense box), Shoji Morinaga (wooden plate).