Returning to the Earth

An essay by Hiroki Kiyokawa

All living things in our world, all the plants and animals surrounding us, must return to the earth when their time comes. This return is natural, indeed inevitable, but generally we do not think of it much.

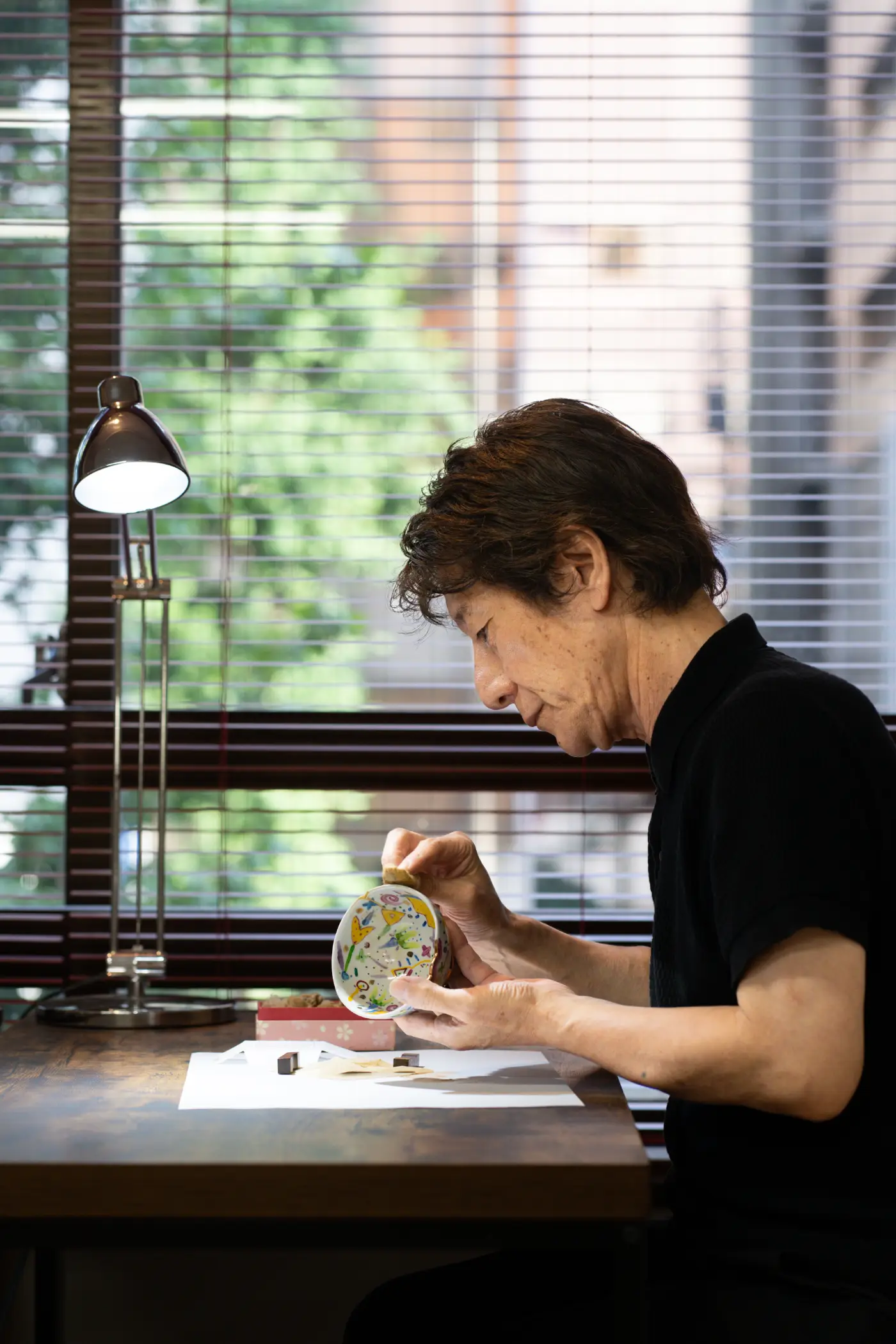

When I do kintsugi, I use only natural materials, and consciously work on the premise that everything should be returned to the earth. When I work with kintsugi, I feel harmony with nature. The multiform arts of lacquerware, including kintsugi, employ processes using the sap of the lacquer tree, the very life-blood of the tree.

When I consider this fact, I feel profound gratitude and respect for nature.

When I touch the work with my hands, I feel acutely that I too am part of the natural world. Like all elements of that world, my body too will eventually return to the earth, becoming part of a new life.

Lacquer hardens and assimilates into the vessel, leaving behind its previous existence and transforming into something new.

The contours of this process conform with the traditional Japanese view of life and impermanence, which encourages appreciation of this very moment, and seeing the panorama of inevitable change as natural, and indeed beautiful, adaptations to the profound endless cycles of life and rebirth.

The Beauty Created by Cracks

The culture of kintsugi was born from and nurtured in chado, the “way of tea”. In their careful and attentive repair of damaged matcha bowls, the tea masters of the Muromachi period discovered, and exulted in, a new beauty of “brokenness”. They grew to see in the cracks and fissures of broken bowls the minute and concrete manifestation of the great process of life and death, and their appreciation led to the application of gold to accent the broken parts.

The techniques of kintsugi restoration give birth not only to a repaired vessel, but to a new view of the vessel by accenting, indeed celebrating, its broken parts.

I do not consider breakage a negative thing. I firmly believe that all things that have form are destined to break someday. Moreover, a breakage creates the possibility of reconstructing the future. Like the tea masters of the Muromachi period, gazing with joy at a once-broken tea bowl repaired with gold, the kintsugi view encourages us to interpret the ‘breakages’ in our life as new starting points, to see damage, disappointment, and failure as profound natural phenomena worthy of appreciation.

Because everything returns to the earth, including lacquer, vessels, and me, I want to enjoy the beauty created by the cracks of age and mishaps of life. I hope that my handiwork emerges with the life of nature fully expressed. I restore vessels so that they may return to the earth peacefully.

Connecting to the Public

An interview with Hiroki Kiyokawa

How long have you been working on restoring vessels through kintsugi?

It is my 50th year doing restoration work. Throughout that period I have been involved with different kinds of restoration, working on the restoration of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples across Japan. My main work there was the restoration and repair of Buddhist statues and classical furnishings from the Edo period. For several decades Kintsugi was just one element of my repair work, a tiny part of a bigger umbrella.

Then ten years ago, I decided to narrow my practice to focus on kintsugi only. I chose to do so because kintsugi and its underlying spirituality can be easily shared with the general public.

When restoring old Buddhist statues or 200-year-old temples, it’s impossible to work with the general public. The quality is simply too high. Only professionals are allowed to work on it.

However, in kintsugi, you can take something that has been broken in your daily life and put it back into your daily life with your own hands, using natural materials. So I chose kintsugi because it is a wonderful and accessible platform to communicate what I have learned and acquired over the past 50 years in a way that allows me to connect to the public and share my message.

Making a Living with My Own Hands

Were you born into a craft family that does restoration?

No, my father was a businessman. He passed away when I was 16 because he was a real corporate man and worked all the time. I think he was crushed by his work.

When he died, I was still a freshman in high school. I felt that the world had changed because my father disappeared. It was a shocking thing for the family left behind. At the time, I resented and hated my father. I always thought he was irresponsible. He left his family, he left his mother, he didn’t take care of himself, and he died so soon. This feeling of resentment lasted until I was about 40 years old.

When I was 18 years old I decided to enter the world of lacquerware as an apprentice. Contrary to my father, I wanted to make my living by myself with my own hands, rather than by my academic background. I was able to join a team of cultural property restorers, and learn the techniques of the Edo period people while repairing many different kinds of cultural objects.

That too must have been a tough path, apprenticing with traditional craftsmen that work on such important buildings and objects?

It was a tough road, but looking back, I think I was able to persevere because I didn’t have a father. Because of that, I had no other choice. I had nowhere to escape to.

When I became able to make a decent living, I began to feel that my father, whom I had resented so much, was actually a benefactor. I began to feel that his disappearance somewhat brought a blessing to my life. At the age of over 40, I finally started to understand.

Could you say more?

There Will Always Be Damage

I used to think that it was my father’s fault that I was having such a hard time, but actually it wasn’t the case. Because my father was gone, I was able to acquire this skill of giving objects new life through the repair work I do with my hands, as well as meeting a lot of people in the business. Now I am in a position to be thanked by other people, and I feel grateful to my father’s passing.

What do you want to convey to the world through kintsugi?

The good thing about kintsugi is that even if something is broken, cracked, or damaged, it can be revived or redone. And if we look deeply, it is the same for us.

As long as we are born, there will always be damage and accidents. But we must not be defeated by them and have to make the next step in our lives. We must not forget that. The difficult experiences can become blessings for us. Because of the difficult things, there will be wonderful things to follow. That is what I am trying to let everyone know through Kintsugi.

This sounds exactly like my life, doesn’t it? That’s exactly what my life has been. I’m just trying to let people know that through Kintsugi.

We Must Never Give Up

Is that the core of the spirituality of kintsugi?

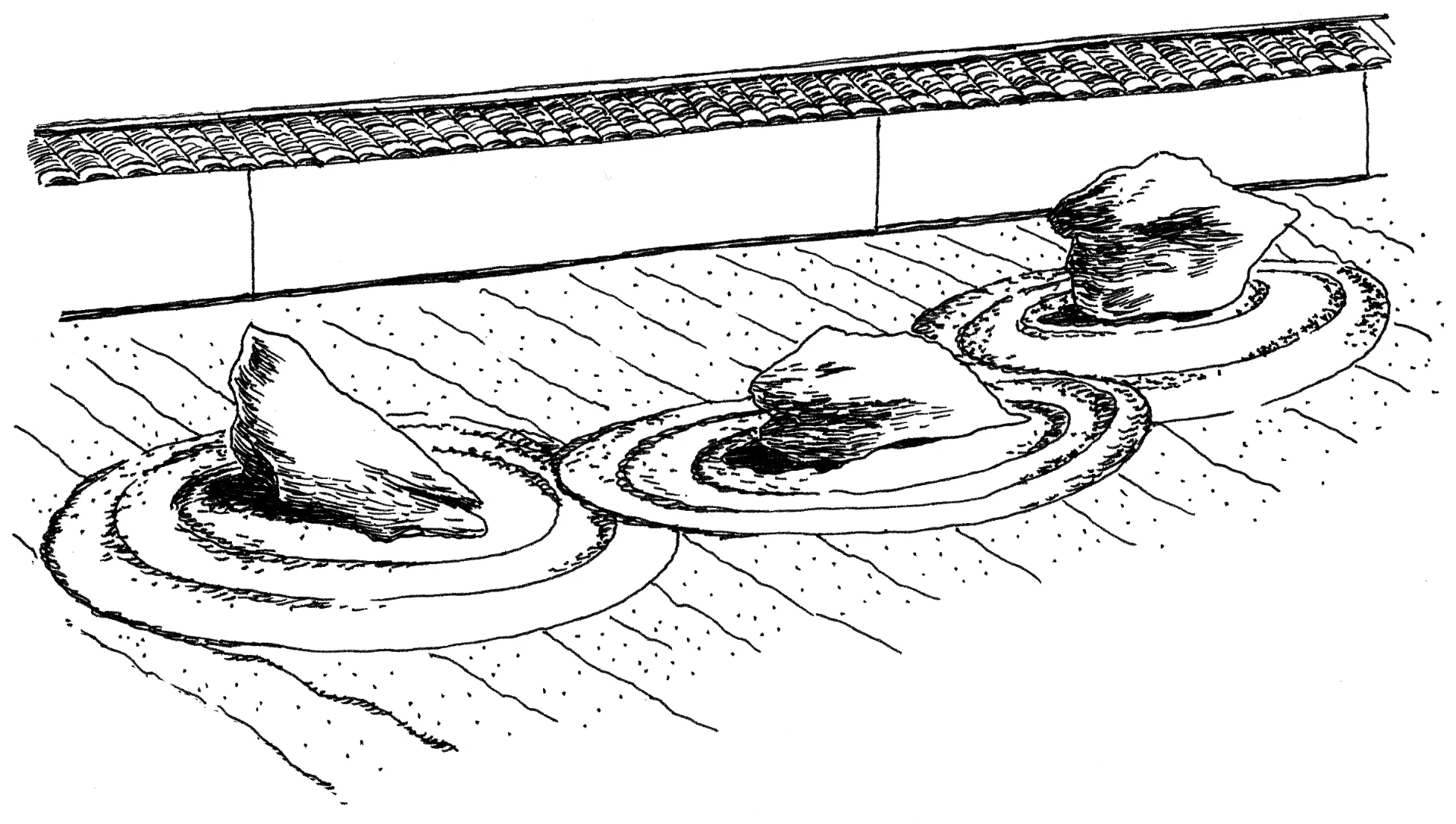

Yes, it is. Kintsugi has a history of 400 to 500 years, appearing along with the Tea culture, but originally, the Jomon people have used lacquer as a mending tool for 10,000 years.

However, the name “kintsugi” appeared along with the tea ceremony culture 400 – 500 years ago. In that period, no one interpreted kintsugi as I have.

I think the current kintsugi boom was triggered by my efforts to create the next stage of kintsugi, and to tell people that kintsugi is not just about repairing things, but also represents a spiritual stance in the world. One that is deeply rooted in Japanese sensibility, but in tune with something universal.

Not only vessels, but many things break down during our lifetime, including ourselves. Each time we are damaged, we have to think about our next self, our next vessel, our next lifespan, our next period after the cosmetic renewal.

We must never give up on that. Never.

Your studio in Kyoto is located opposite of Daitokuji, one of Kyoto’s most important Zen temples. And as a restorer, you have had a lot of opportunities to come in contact with Buddhism and Shintoism.

Lacquer Has a Soul

Are there any Zen or Shinto teachings that resonate strongly with your kintsugi work?

Based on the Shinto belief of ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami’, that there are 8 million gods or divine spirits, Japanese people see the divine in everything. This belief is also at the heart of kintsugi, though it is not only specific to kintsugi.

In kintsugi, we receive the sap of the lacquer tree to make lacquerware. Their sap is like the blood in our own body. By giving its blood, a lacquer tree that is 10 years old will die within six months. In order to provide a cup of lacquer sap, the life of the lacquer tree is exchanged.

That is why we believe that lacquer has a soul.

Buddhism differs from Shintoism in that it teaches us a way of life through its practices and doctrines, which is also important. I think that Buddhism, along with the tea culture, teaches the Japanese how to live.

But of course our lifespan is only 80 to 100 years. No one lives 300 years, so Buddhism invites us to reflect on how to use the precious time we are given in a good way. It invites each of us to reflect on the question, “What role was I born to play during my lifetime?”

How do you see the future of craft and what’s most essential to keep?

I’m often asked how I see craftsmaking in 100 years. But I’d say, if we really want to think about 100 years from now, we should go back 100 years. Everyone is only looking forward, only looking ahead. Instead, I think it’s important to also look back 100 years and examine what we have gained and lost since. And then to ask ourselves, have we lost anything important?

We have gained some wonderful things, but we may have also lost some things that we should have cherished.

A Good Balance

What do you feel we have lost or are losing?

It is very important to create things with sensitivity, and I think that a good balance between modern and classical culture must be preserved for all time.

AI and IT alone will not be enough to build a good country or society. It can only generate things based on data. So we need to preserve and cultivate people with such wonderful human sensitivity, as well as the handmade products only they can create.

Japanese society tends to judge people based on their deviation score in school, academic background, and so on. But I don’t think that should be the only measurement. There are many people who may not do well within this narrow measurement, but are capable of making things. We should be able to appreciate more diversity.

It is natural that each person has a different way of thinking, and we should recognize their individuality. I think that’s true education. There must be something that each child can only do, and you, as an adult, have to help them find it in an early stage and cultivate that.

I think the real education is to give them the ability to manage their life by themselves.