Disconnected

In a culture obsessed with speed and growth at all costs, many of us are living from the neck up, disconnected from our bodies, other people and the natural world. Convenience and efficiency seem to have trumped meaning and feeling.

I often feel like I’m living in a binary state, behaving more like the digital devices that permeate every aspect of my life than the complex and multilayered human that I am. It’s as if the more capable our gadgets become and the higher the definition of our screens, the lower the resolution of our actual lives.

To fight back and stop living inside my head full-time, I embarked on a month-long research trip to Japan to learn how to feel more from the shokunin, craft masters. The trip was a continuation of my ongoing research into Japanese craftsmanship as a possible guide to live and work better.

After many years of visiting Japan, spending time with its artisans, and helping to promote their work abroad, I have come to believe that they are stewards of knowledge that can help us all, not just craftspeople, lead more fulfilling lives. This is largely because of the artisan’s need to maintain a balance between the thinking that happens in their mind and the thinking that happens through their body. There’s also an element of circularity involved.

Circular Traditions

These traditions developed long before digital technology permeated modern life, and they have roots in circular principles. For example, the maker must be in close communion with the source of their raw materials, often nature. They need to understand when these materials are at their best for optimal performance and know how much to extract without depleting the resources on which their livelihood depends. If you take too much, you’ll soon be out of work.

Then there is the direct relationship with the customer, who was once always a local person. You couldn’t get away with producing low-quality products because they knew where you lived. Most importantly, the craftsman had to pay attention to the knowledge passed down from their predecessors and reflect on how they adapted to current conditions, gradually evolving the tradition to stay relevant.

Staying connected to the past while maintaining a solid practice grounded in the present and looking to the future—finding balance with the source of your materials, with the customers you serve, and living and working fully with body, mind, and spirit aligned—that’s what I wanted to explore further and experience directly.

To Know And Not To Do Is Not Yet To Know

I chose the autumn season because it’s a time of transitions—from the leaves that change from vivid green to bright reds and yellows, to natural flavors that have captured the intensity of the summer months. It’s a season that invites us to pay attention in a different way, to attune to subtle changes happening around us and inside of us.

I sought out activities that would allow me to be fully present, to pause and savor the moment.

During that month, I made soba, buckwheat noodles, in Tokyo with the former teacher of Steve Jobs’ private chef. I visited metalworking workshops in Toyama, which are evolving century-old traditions. But the experience that marked me the most, and has had the longest-lasting impact, was making ceramics in Uji at Asahiyaki, a pottery with a 400-year-old history.

Making Ceramics In Uji

Uji, a town on the outskirts of Kyoto, is renowned for producing the best matcha in Japan and credited with inventing sencha in the 18th century. It’s also the setting for The Tale of Genji, a classic novel written in the 11th century by Murasaki Shikibu.

A year earlier, I was sitting at the long table of Asahiyaki’s gallery space, chatting with Hosai Matsubayashi XVI about life and work. Hosai san is the 16th and current head of the Asahiyaki kiln. I shared with him how I felt that the overlap between what I do for a living and what brings me joy was getting smaller. For Hosai-san, it was the exact opposite, with an almost perfect overlap between the two.

“I love tea and I love ceramics!” he told me. Ceramics and tea culture are also close to my heart, and it was during that meeting that he invited me to return the following year to hone my skills at his workshop. It felt like a dream come true!

However, I must confess that as the date to visit grew closer, the prospect of working under the watchful eye of a 16th-generation master craftsman made me anxious. ‘Will I waste his time?’ I asked myself. I’ve been making wonky pots on and off for a couple of years without much continuity. I understand the process intellectually, but my body hasn’t retained enough knowledge to get the results I want.

Thinking With The Tips Of My Fingers

When I first touched the local clay, I realized I was in trouble. It was much softer than what I was used to in London! Asahiyaki’s hanshi clay is collected from the river and mountains surrounding Uji and aged for several decades before it’s ready to use. Very little water is required when handling it; to keep things running smoothly, you just coat your fingers with the slip, liquid clay, that’s generated during the process.

In pottery, ‘throwing’ refers to creating vessels by manipulating the clay on top of a rotating wheel. In the UK, it rotates anticlockwise; in Japan, it’s clockwise. To make matters more challenging, throwing was done ‘off-the-hump,’ a technique where you put a big pile of material on the wheel to make multiple objects in a row, as opposed to using just the amount required for a single pot. I was also encouraged to practice using very few additional tools to develop a better technique. The only way forward was to accept that the conditions I was used to had changed and that I would have to relearn how to make pots in this new environment.

Sitting at the wheel for six hours on three consecutive days was conducive to feeling and thinking more deeply. It was as if my brain had moved from the inside of my head to the tips of my fingers, in direct communion with the clay. My limited Japanese vocabulary meant that instead of talking with words, any time I needed help or advice, I would have to speak through what I was making.

On the second day, my nerves subsided. I was no longer embarrassed by the lopsided bowls that formed under my hands. Throwing off the hump allowed me to enter a state of flow by not needing to stop and reset the wheel continuously. I was getting at least one percent better by using each piece as feedback and carrying those learnings onto the next one.

Body-Mind As One

Pottery forces you to slow down and get your whole body and mind in sync. It’s humbling and keeps the ego in check. It’s not just about accepting that much of the work happens through actions that arise from muscle memory and intuition, and not from your intellect, but also that the quality of the work depends as much – if not more – on the quality of the source materials, the knowledge passed on from other makers and the finalizing effect of the fire in the kiln. As Kawai Kanjiro, the late potter and co-founder of the Japanese folk-craft movement once remarked: we do not work alone.

Much like in Zen Buddhism, cleaning plays an important part in the life of a potter. When I started at Asahiyaki, one of the assistants, Endo-san, noted how much clay I was discarding (or getting onto my clothes), a sign of poor technique. The better I became at making, the less there was to clean. At the end of each session, I measured my improvement by how much less messy my workspace was. Although Endo-san was not there to see it, I was proud that when my residency came to a close, I had reduced the amount of wasted clay by almost two-thirds!

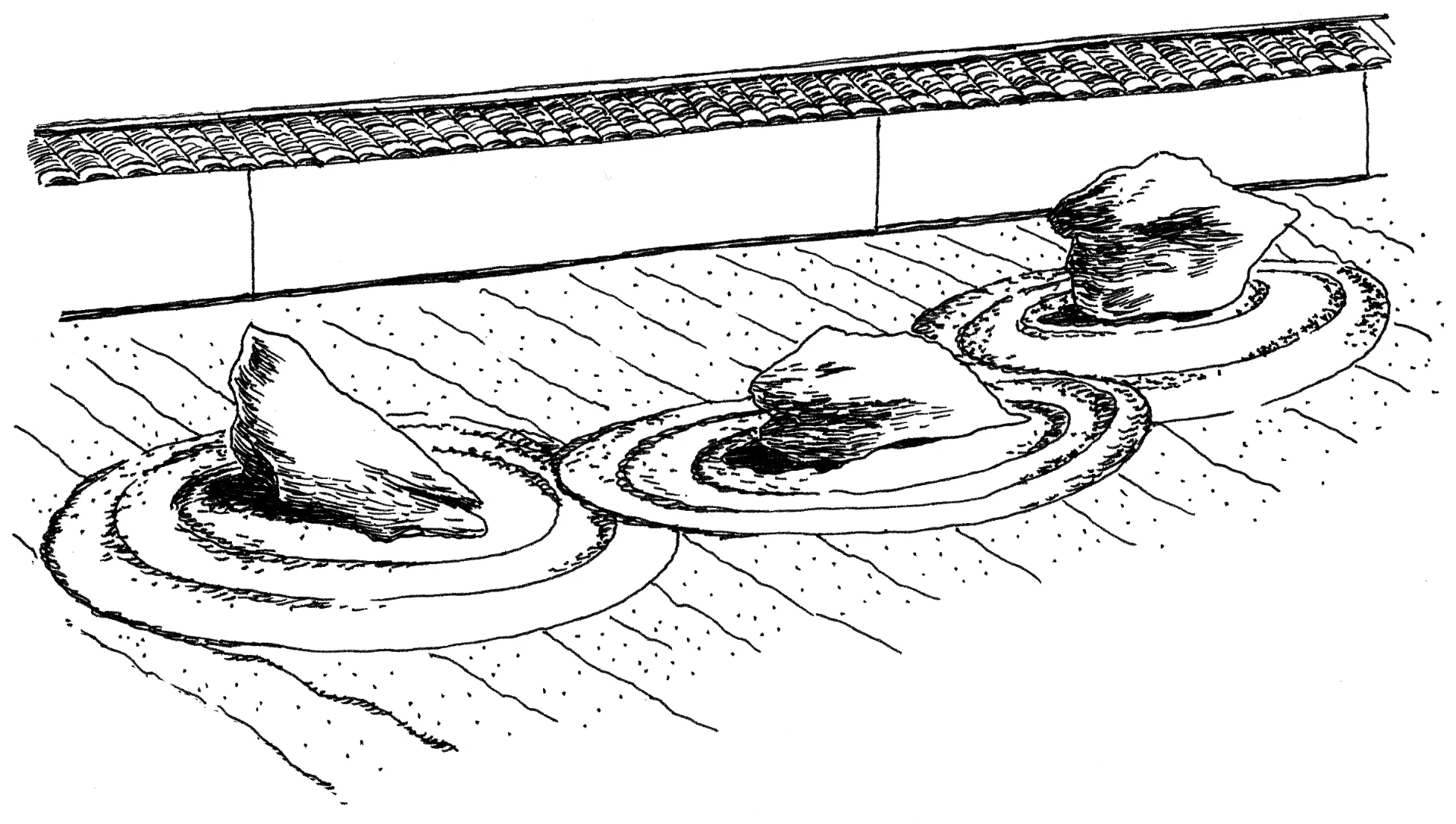

In the end, I produced about thirty pots. I selected a dozen of them to be glazed and fired, while the others would be destroyed and the material recycled. It was an exercise in letting go: it’s hard to avoid being attached to what you make, but it would be unsustainable to keep everything.

Learning to Let Go

Choosing was hard. I had to move beyond the sentimental bond I had formed with these objects. What was their reason for existence? I kept those that I felt communicated the essence of the past few days in Uji, sitting at the wheel, pieces that would serve as a beacon, reminding me that my idea of a life well lived is broader than I imagine. Yet, compared to Hosai Matsubayashi’s approach to pottery, I wasn’t critical enough. Despite his many years of experience, he approves only about ten percent of the objects he makes, those that are true to his ethos.

But the life lessons weren’t over yet. Just as a specific clay will influence the results, so does the fire in the kiln, which acts as a co-creator, especially when you use wood as fuel (my pieces went into a more predictable gas-fired kiln). Because there wasn’t enough time to apply all the different combinations of glazes I wanted to try and fire the pots before I had to leave, I left notes with instructions for the staff to finish them on my behalf.

It took almost four months until a big box from Japan was delivered to my home in London, and I could finally see the result of my efforts. The wait provided further training in patience, a quality all craftspeople must have. I was very happy with the results—they looked better than I remembered! Did the staff at Asahiyaki improve them with their glazing and firing techniques, or was it the temporary detachment from my creations that allowed me to judge them with fresh eyes?

Today, when I drink tea or eat out of one of the pots I made, I feel satisfied in a way that a mass made product, even a well made expensive one will never give me. These objects have no real market value, but they’ve enriched my life more than anything I could buy.

Feeling More Is About Caring More

My research in Japan reminded me that to feel more you don’t have to go somewhere far away or do something special to increase the resolution at which you live your life. It doesn’t require any special equipment nor money.

The challenge then is not how to undertake one-off activities to offset the numbing time spent behind screens. How to feel more is as much an attitude as it is being in tune with your senses. It’s about caring more about how you experience the world, letting go of the vacuous extremes guided by someone else’s agenda and rejoicing in the messy middle. The key might be opening ourselves more to living seasonally, with less but better things, appreciating friendships and relationships for what they are and not for what they pretend to be.

The opportunity to engage in mindful presence is all around you, all the time.

Gianfranco Chicco is a London-based curator, marketing strategist, writer and a Japanophile working at the intersection of design, technology and craft. An engineer by training and a storyteller by vocation, he bridges the digital and physical worlds to create unique experiences that enrich and delight audiences, opening new perspectives on business and culture.