Have you always lived in Kyoto?

Ko Kado: I was born and raised in Kyoto. But my father is from Shimane and my mother is from Saitama. They came to Kyoto for work and got married, and I was born near the Kamigamo Shrine. So yes, I was born in Kyoto, but I am not a Kyoto person from the more traditional Kyoto people’s perspective.

But this kind of ambiguity or in-betweenness can also be useful. I could say that I’m from Kyoto because I was born in Kyoto, but when it comes to more complex local sensibility issues, I can also say my parents aren’t from Kyoto. I’m switching to either flexibly.

After first going to art college in Kyoto, you decided to study design in San Francisco. What inspired you to go abroad?

I always had a strong desire to go abroad. I knew it wouldn’t be easy to live abroad once I started working. So I talked to my parents about it and they supported me.

My father’s family was poor, so he didn’t have any financial support from his parents. He wanted to go to university in Tokyo, but it was impossible. He could only go to the national public university in Shimane. He entered Shimane National University and became a civil servant in Kyoto. So when I said I wanted to go abroad, he told me I should just do it.

How did you decide where to go?

There are only so many English-speaking countries. I looked through a guidebook and picked the cheapest language school I could find, which was the one in LA. It was insanely cheap. $450 a month including an apartment. So I applied, got accepted and then it turned out it was in the middle of Chinatown. Some people were from Russia or ex-Soviet countries, and the rest were all Asians. Even all the signs were in Chinese characters, so even though I had just moved to the other side of the planet, I didn’t feel like I was in the United States at all!

“I realized I’m more drawn to work that is closer to my body.”

After completing language school in LA, you entered an art school in San Francisco. What did you discover there about yourself and what you’re most drawn to in your work?

I had the opportunity to visit a printing company as part of my class. I was going to make my own books, so I went to visit various printing shops to gain hands-on experience. At that time there were a lot of letterpress printing studios in San Francisco. And when I went, the letterpress machine was working in full, I could hear the cranking. A craftsman was attending it. The space was filled with the smell of ink. It was amazing!

That’s when I realized I’m more drawn to work that is closer to my body, more physical work than just flickering through a computer screen.

I began to experiment with printing techniques. I also used the back of the paper, or incorporated the misprints of the photocopier into the graphics to create my artwork. My approach had a kind of analog touch and that was interesting to me.

As everyone else in my class was going deeper and deeper into Photoshop and digital skills, this analog approach made me the odd one in the classroom. I believe that’s why I was able to graduate, majoring in printing. Then I found a job at a magazine company in New York.

“Even back then, I had a sense that handmade things would be valued more in the future.”

How did you discover karakami?

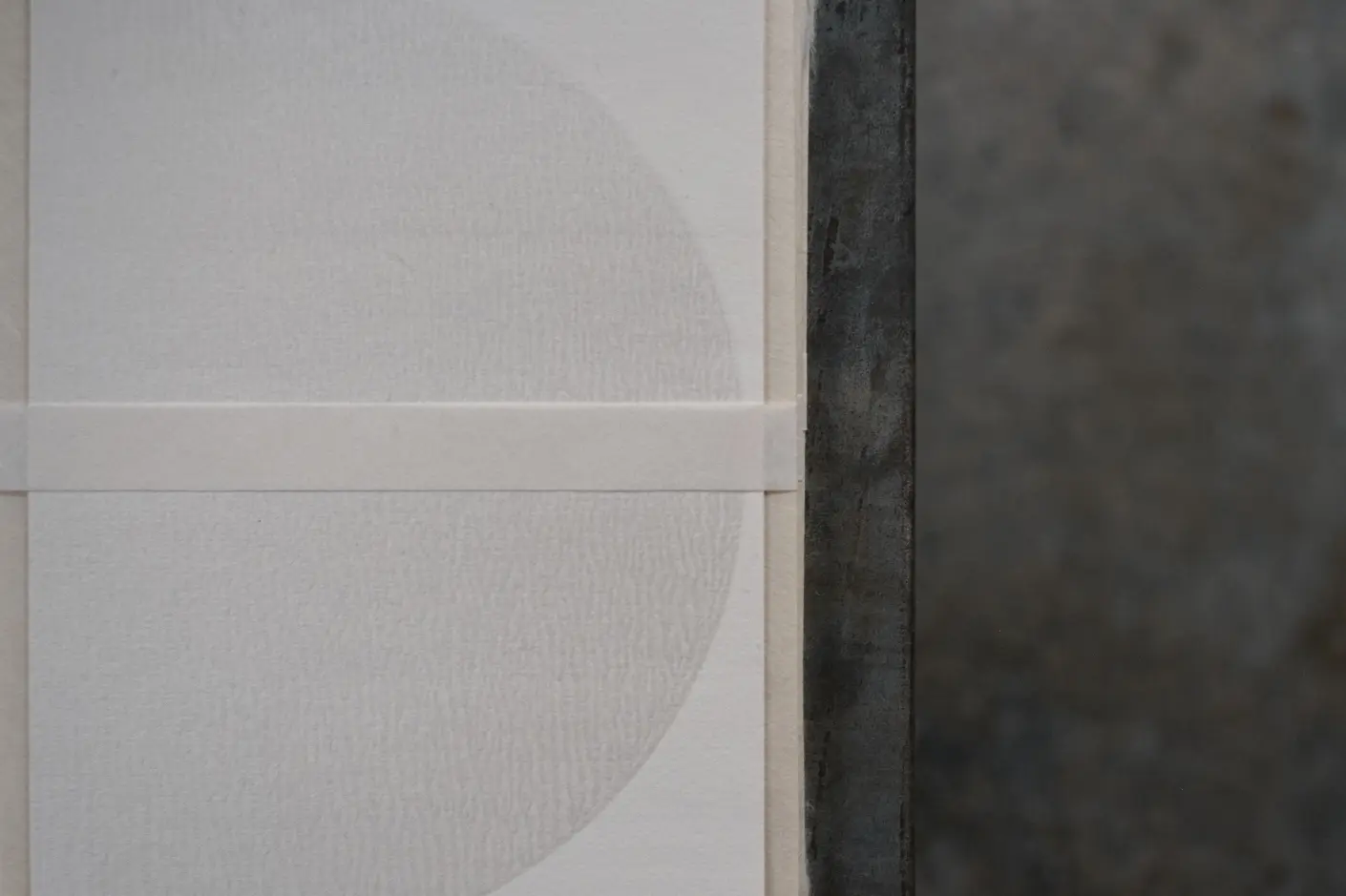

When I came back to Japan for a break, a friend of mine told me that there was an interesting place to go, which was Karacho. Karacho is the oldest karakami company in Kyoto, dating all the way back to 1624. There, I was shocked by the amount of information I received with all my senses from just a single color print on Japanese washi paper.

In computer graphics, the amount of information in the data is insanely large; the number of layers and circuits in the image… yet, when I see a final image on a sheet of paper it doesn’t stir much emotion in me. But when I encountered the hand-printed paper works at Karacho it was the exact opposite. I was amazed to see such a nuanced expression was possible on a two-dimensional medium like paper.

And these were postcards. The main Karakami works are for sliding doors and folding screens, which was not something that ordinary people could see. So, in the shop, they had a regular postcard with patterns printed with one color. However, the color of the pigment seemed unusually rich and evocative. Each pattern was big, with lots of empty space around it (yohaku 余白). The printed lines themselves were bold and their fluctuation was evocative. I thought it was something between a brushwork and a woodblock print.

Did you enter Karacho then and there?

No, I first returned to New York as I was still working at a magazine company there. But after a while, I decided to come back to Japan and started living in Kyoto. I thought about ways to make use of my experience and knowledge so far.

This was back in 2003. At that time there really wasn’t that much interest in handmade crafts like there is now. However, even back then I had a sense that such handicrafts would be valued more in the future. At the same time, more and more tourists began coming to Kyoto, and I could speak a little English. All that played a part in my acceptance into Karacho as an apprentice.

“For the first time, I realized that I was this person, content on my own.”

What was it like to switch from New York to Kyoto? From high-paced magazine design to learning the traditional craft of analog paper printing at Karacho?

K: In New York, I did the job I wanted to do, and it was fun, but it was also hard and exhausting. I was surrounded by people all the time, meeting with a lot of people every evening. And though I was drawn to analog work, the reality there was that I always worked behind a computer.

Then when I started to work as a craftsman in Karacho, everything shifted. There were days when I would not talk to anyone at all. It was the time to have a conversation with myself.

I would get completely absorbed in mixing the natural pigments for coloring, or counting sheets of washi paper all day. I felt comfortable and at ease there. For the first time, I realized that I was this person, content on my own.

What else did you discover at Karacho?

To welcome ambiguity, or what in Japanese we call ‘aimai’.

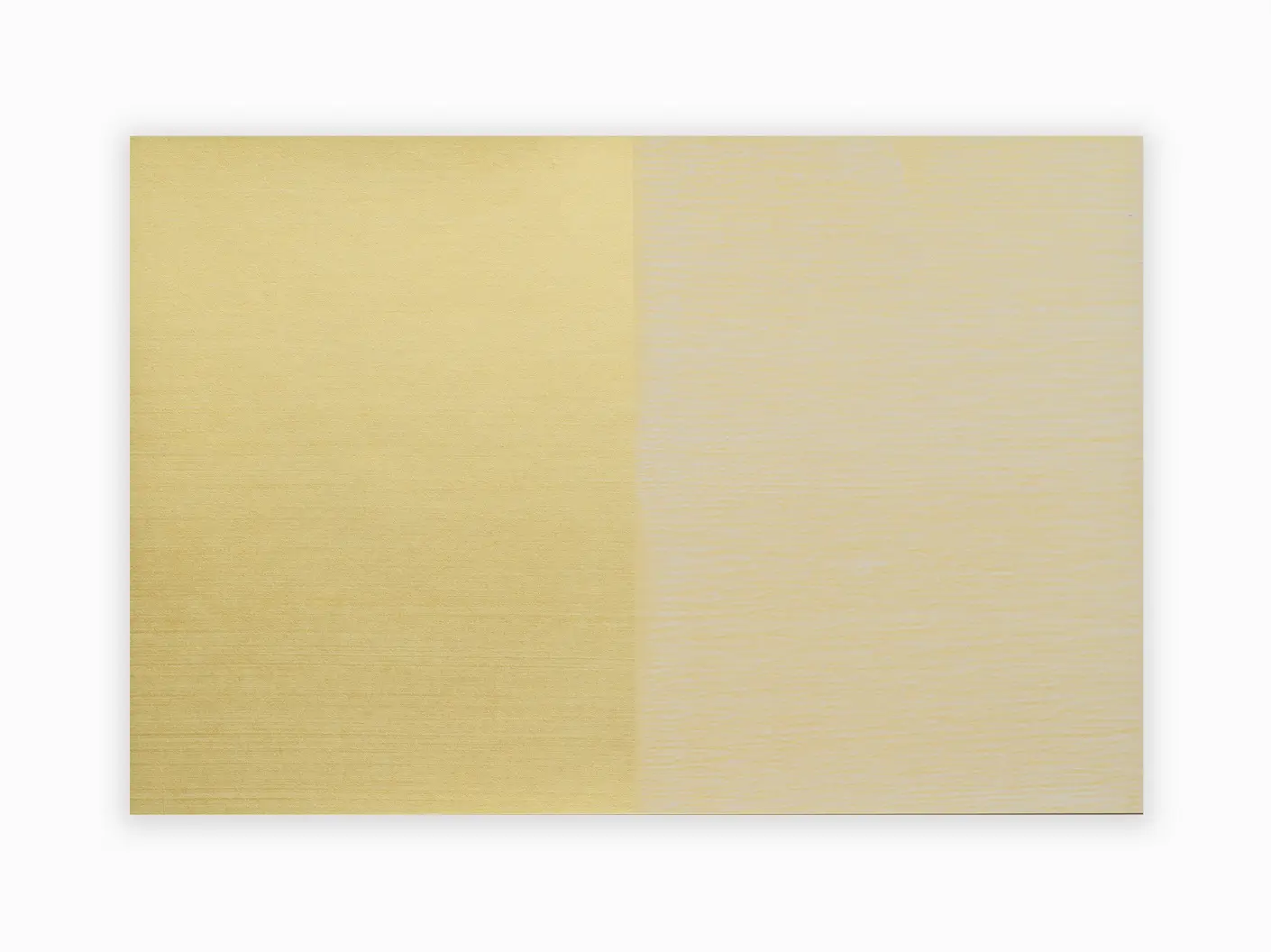

The color produced by mixing pigments is very subtle. There is no fixed recipe for that. How the color comes out after mixing depends on the temperature and humidity of the day too. So even if I was told to bring out one particular color, it doesn’t always match perfectly. Yet I was told that this is fine. That, if I stepped back 2 meters and had a look, and thought it matched the atmosphere as a whole, it was fine. I thought to myself, what a wonderful job this is!

“There is no universal truth to beauty.”

Could you say more about the value of ambiguity or “aimai”?

My master told me that there is no such thing as “right” or “wrong” in karakami. There is no manual for karakami, no set rules of what it is supposed to look like. That is exactly what makes it so fascinating.

What I learned from him is to embrace the ambiguity that is inherent in the craft. To accept the fact that beauty in karakami can’t be clearly defined. The things people find beauty in depend on how they feel, on the season, on the weather. There is no universal truth to beauty.

Let me give you one example to illustrate:

I went to deliver my work to the client, and he told me that it was a different color than he had specified. He said that the color didn’t give him the right feeling. Well, I wasn’t happy, but I said I’d do it again.

The next day I brought the same one. And he said “Yes, this is the one!”

I thought that he was probably in a bad mood yesterday.

That’s so interesting!

How about yourself, where do you find beauty and inspiration for your day-to-day work?

Everywhere. There are endless sources of inspiration in my daily life. From movies I’ve watched, museums I’ve visited, to the surrounding mountains.

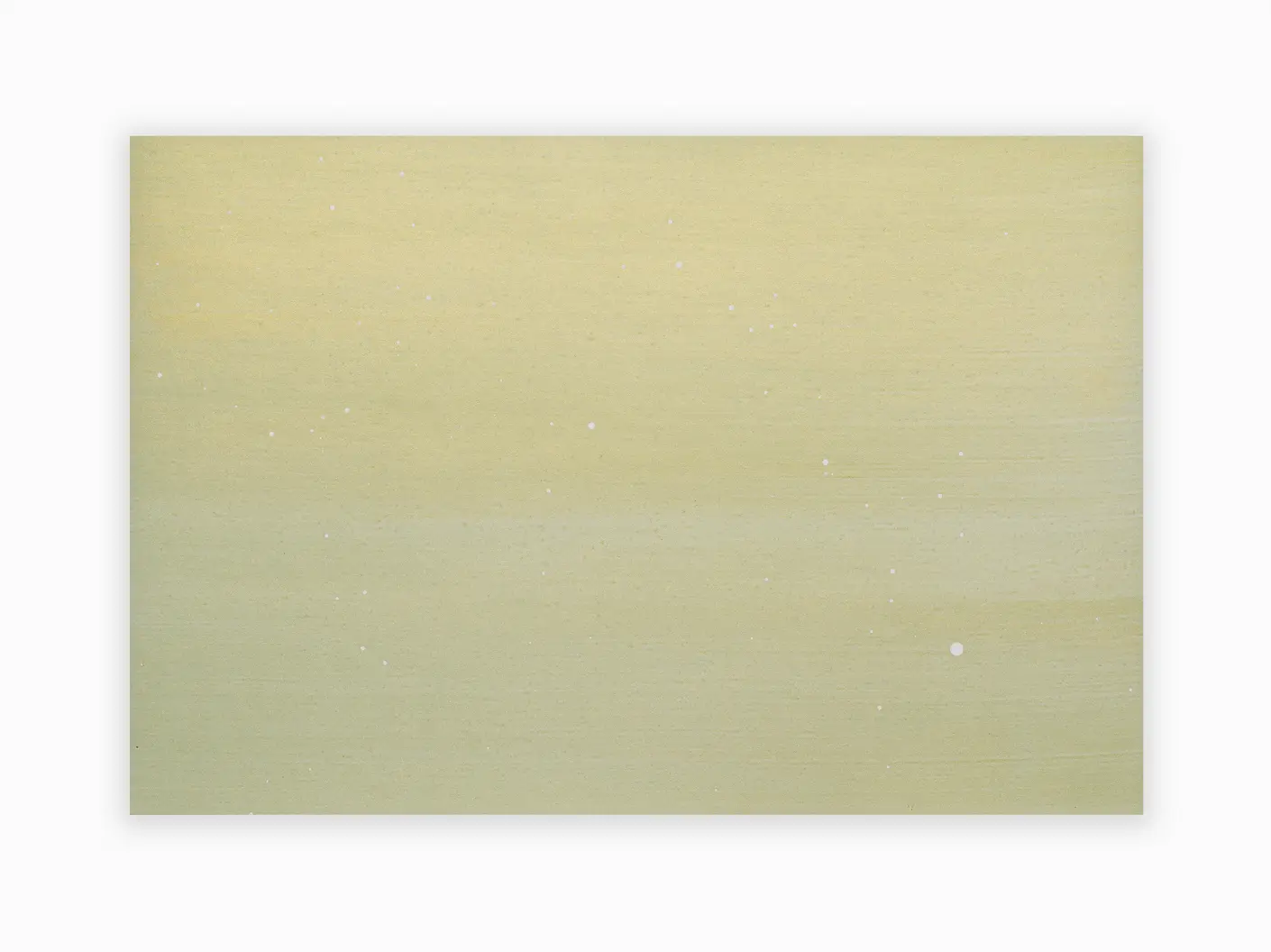

I might try to recreate a beautiful color I’ve seen that stays in my mind, or give shape to the rough texture I noticed at a building site. Or I will try my hand at bringing the feel of an old temple’s decaying wooden structure to life on paper.

I receive this kind of beauty all the time, even when I’m driving. This type of beauty feels very near in Kyoto, partly because the people here are highly critical of their surroundings.

“I work towards discovering novelty in the past and bringing it into the future.”

Your work draws on traditional techniques and yet feels very contemporary, almost timeless. How do you balance tradition and innovation in your work?

I did not come from a craft family. Instead, I entered the craft after living abroad and first studying and practicing graphic design. Maybe this allows me to see things differently and discover tradition anew.

Karakami has been around for about 400 years, and the Karacho studio has honed its craft by following this evolution from the very beginning, while I’ve worked my way back from the present day. For me, exploring the materials and techniques that were used in the past is filled with new discoveries.

Could give us an example?

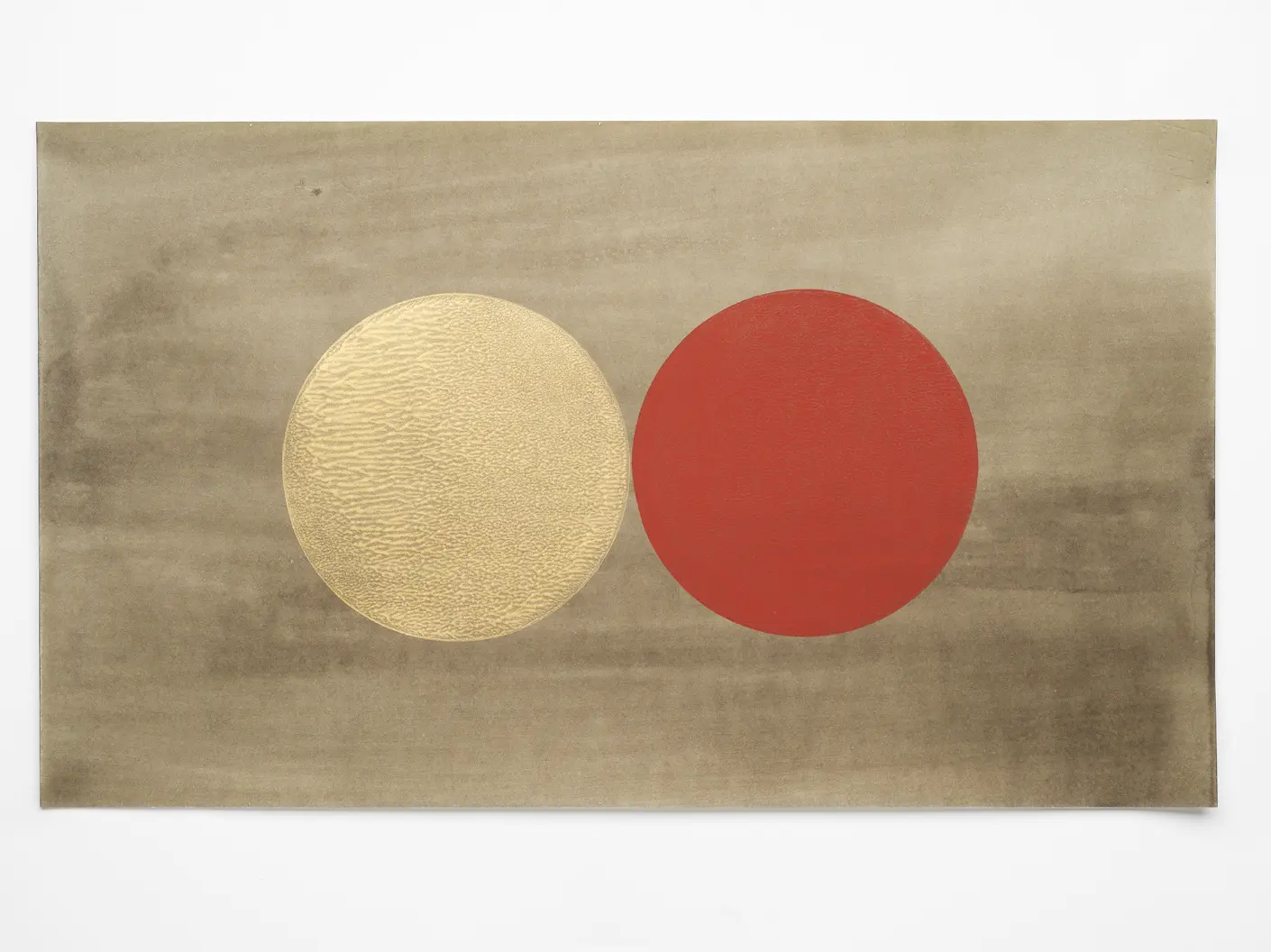

Many people say my white-on-white works are ‘typical Kamisoe’. For those, I apply white mica powder on white washi paper to create a very subtle luster. At Karacho this is the basics of the basics in terms of technique. A first step that has existed since the very beginning of karakami tradition 400 years ago. Nothing new.

But because I joined the line of tradition only recently, I can see these things with new eyes and find beauty in the most basic and simplest forms .

White on white speaks true beauty to me even now.

So from my perspective, creating something new has nothing to do with using new materials or techniques. I work towards discovering novelty in the past and bringing it into the future. That is also a type of progress. People may feel the only way forward is to go towards the undiscovered that lies in the future, but re-discovering the past is also a way of moving forward.

“There is no need to understand everything around you.”

How do you see the future of craft and handmade things?

I’m positive that as our lives and society continue to digitalize, our desire for and appreciation of handmade things will also increase. Things made by hand speak to our senses and heart in a completely different way than digital and mass produced things do.

People are always attracted to both poles. We only understand the value of something in contrast to something else. If you don’t have handmade things, you won’t appreciate the benefits of digital things. The same applies the other way around.

Any final reflection or invitation to the reader?

K: Embrace ambiguity. There is no need to understand everything around you.