Rooted in Daily Life

Could you tell us where you were born and grew up?

I was born in Kanagawa and grew up in a residential area of Yokohama. I didn’t grow up in a particularly “traditional” Japanese family or culture. However, both of my parents’ families served Shinto shrines, so we would visit shrines for summer festivals and New Year’s celebrations, and forests that surrounds these shrines used to be my playgrounds.

We also had a kamidana (神棚) – Shinto altar- at home and my job as a child was to make a rice offering every morning. If we received a gift or the first harvest of the season, we would first offer it to the alter, and then we would enjoy these gifts after our deities.

If I visited my friend’s house, I’d first greet to their alter, just like I would do at any shrine.

I didn’t used to think of it as “religion” or “faith” or anything like that. It felt very much like a naturally embedded part of my daily practice. Also, although I felt the existence of the deities very close to me, I never formally studied Shinto nor learned about it from my parents or grandparents.

You are currently studying to become a Shinto priestess.

What inspired you to do so?

Moving here, northern Kyoto, had a huge impact on me. After getting married, I moved here and became a parishioner of a nearby shrine. As a parishioner, I would join the seasonal festivals and received the ritual offerings afterword. For example, we offer kagami mochi (鏡餅 ) – the rounded rice cakes for New Year’s, and after a certain period, some broken pieces of kagami mochi will be shared among the parishoners. For the ritual of celebrating the beginning of spring, we receive roasted soybeans.

There’s also a purification ritual called Nagoshi no Harae (夏越の祓). People transfer their impurities accumulated in the past six months onto human-shaped paper dolls, and wish for their well-being for coming six months.

Growing up in a residential area, I never really felt the change of the seasons so vividly, but living in the countryside, I became more aware of it: how rice fields turn green in summer and then bear golden grains in autumn. And that made me also see how shrine festivals align with the seasons. These festivals are deeply rooted in people’s daily lives, and through them, abundance goes around and is shared by the community.

Feeling My Heart Being Purified

That’s how you came to appreciate the importance of small village shrines.

Yes. The turning point for me was when a close friend of mine decided to take on the path of Buddhist priesthood. I was about to turn 40 at the time. I thought, “If 40 is the halfway point of my life, how do I want to spend the second half?”

I wondered if I could learn more about Shinto, which is part of my roots. I couldn’t conceive a child, but I may be able to pass on what I’ve learnt and the culture to the next generation by becoming one of the people to protect and preserve the village shrine.

How was the training experience?

I went to a shrine every day and served there for a month. Until then, I had only served for shrine duties during festivals, so it was my first time helping the daily maintenance.

One of the things left me with strong impressions was the daily practice of the priests. Every morning, they wipe everything down, sweep the fallen leaves, to purify the space. The reason for this is that the shrine is the place where the deity resides, so it must be kept clean at all times. It’s the task repeated in the same manner day by day.

Even though leaves will fall again, they are swept away daily. Those that can’t be collected with a broom are picked up by hand, ensuring that the place is completely purified every day.

As I cleaned the shrine, I felt my own heart being purified as well. I could truly experience this deep-down in my body.

You once mentioned that having a shrine is synonym to preserving nature.

That’s right. The belief is that deities dwell in nature. In the past, there weren’t shrine buildings like we see today. Instead, people worshiped at natural objects like rocks and waterfalls, believing that the divine manifested in them. That was the original form of Shinto.

For example, some sacred rocks are adorned with with shimenawa (しめ縄) – sacred rope. These were likely objects of faith.

Living Each Day to the Fullest

Was there a particularly important lesson you learned from the training?

There is a Shinto concept called Naka Ima (中今), the combination of the Kanji characters “Middle” and “Now.” It means “the present moment.” I don’t know if it’s appropriate to call Shinto a religion, but its core belief is to cherish the present.

It’s about living fully in the present moment, which is connected to the past and extends into the future. In Shinto, there is no concept of an afterlife or reincarnation. Instead, the focus is on living each day to the fullest, together with the deities of nature.

This idea is connected to the daily sweeping of fallen leaves, which is a way of resetting everything to zero. Shinto values purity above all else. The act of sweeping in the morning is a ritual to remove impurities and restore oneself to a pure state. That’s the essence of it.

So it’s about constantly removing accumulated distractions, like clearing away unnecessary thoughts? If we let them build up, does it become harder to stay in the present?

In my view, neither being too good nor too bad is ideal. Maintaining a neutral, balanced state of mind is important.

Many events occur every day, stirring our emotions, but it’s imperative to be reminded that we are all given this life to live here, today, in this vast nature. With that in mind, I try to bring myself back to the middle, not too up nor too down.

Starting Anew Each Day

So, being present means maintaining that neutral state?

Yes. Many people visit shrines for New Year’s. I think the essence of it is about resetting and starting fresh. It’s not necessarily about seeking special blessings. The same goes for visiting a shrine or praying at a household altar. While it seems that you are facing the deity, it is also a time to reflect on yourself. By taking that time every morning to reset and start anew, each day builds upon the last, leading into the future. That’s how I interpret it.

That idea connects to sweeping away fallen leaves every morning. Do you have any personal rituals for resetting yourself?

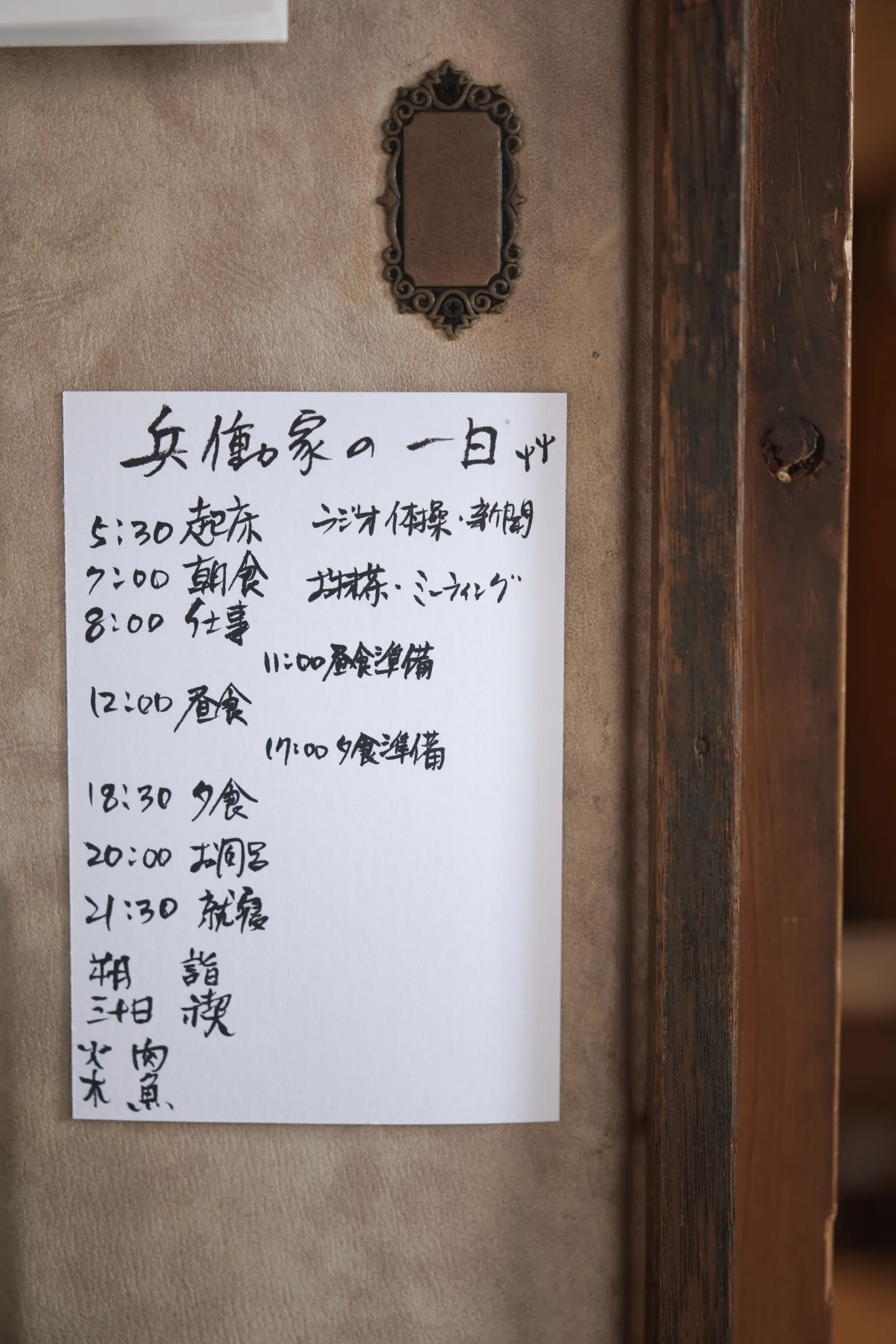

Every morning, I first wash my face and greet to myself in the mirror, then my first job is to replace the rice, salt, and water on my altar.

I take the previous day’s rice, toast it in a pan until it slightly browns and pops like tiny flowers, then add it to hot water along with a little salt, also from the previous day. I drink this to cleanse my body from within. The idea is to become one with the deity by consuming the same food.

After that, I recite the Oharae Norito (大祓祝詞) – purification prayer. It’s a chant that has been passed down for about 1,300 years and is traditionally recited during festivals. The first part tells an ancient story, and the main part focuses on purification of sins and impurities. As humans live, feelings like jealousy and various distractions naturally build up. This prayer is about purging those negative influences and returning our mind to a clean slate.

My husband and I recite the chant together every morning, and then face each other and express our gratitude for each other’s presence for the day.

Practicing the Way of Tea

Going back a bit—when did you move to Kyoto?

When I was 25. Until then I was a very active member of the Scouts, like, going on outdoor camping to uninhabited islands with a big group, etc. But once I felt satisfied with that aspect of my life, socializing and exploring outside, I wanted to experience something completely opposite—something that required deep inner-reflection.

My mother suggested tea practice, so I decided to try it and immediately found it fascinating. After a year of practice, I thought, “If I’m serious about tea, I should go to Kyoto.” My tea teacher introduced me to a traditional tea utensil shop in Kyoto that was looking for an in-house assistant. So, I moved there.

What initially fascinated you about tea ceremony?

During my first tea lesson, I was surprised to learn that you must finish eating the wagashi – traditional sweets, before drinking the tea. I had always alternated between eating and drinking, so this felt very new to me.

The wagashi served in tea gatherings are seasonal and beautifully crafted. You take time to appreciate them visually before eating.

Once you’ve finished the sweet, you naturally start craving tea. Just at that moment, the host serves it. As you draw the tea bowl close, you first notice the fresh aroma of green tea, then, as you drink it, the tea slowly warms your body from inside.

By following this sequence—fully savoring the sweet first and then enjoying the tea—the experience of both elements is enhanced. That realization deeply moved me.

It also intrigued me to watch the host, dressed in a kimono, prepare the tea in elegant movements, all for me to enjoy a cup of tea. From my very next lesson, I started wearing kimono as well. I continued practicing tea once a week, and now it has been about 17 years.

Preparing Yourself a Bowl of Tea

Do you also enjoy tea outside of formal lessons, in your daily life?

Yes, I enjoy tea every morning. After breakfast, I take a little time to enjoy a sweet and then prepare a bowl of tea. It’s a moment of mindfulness, making tea for myself with care.

Did this daily habit inspire your concept of “Own Tea” ?

Yes. In today’s world, we are constantly looking at our phones, listening to music, or watching TV. We rarely take time to focus solely on ourselves.

Traditionally, tea is prepared for guests, but I started making tea for myself, possibly as a way to take myself out of that daily noise. Tea ceremony involves precise steps—warming the tea bowl, cleansing it, and preparing the tea with focused movements. This process naturally brings a sense of mindfulness.

Focusing on a single object with full intention, is a flip side of knowing that “This moment will never come back.” That knowing is also represented in the famous saying Ichigo Ichie (一期一会 ) – and in Naka ima.

I felt that this idea of tea connects with Shinto teaching and wanted to share it with others, so I came up with the name “(My) Own-Tea” to introduce the practice.

You have also been introducing this concept overseas.

Yes, last summer, I went to Los Angeles and introduced tea to 150 people. It was done in a simple manner on a small tray, but the idea was for the participants to prepare their own tea.

First, I demonstrated how to make tea and explained the way to drink it. Then, for the second serving, participants made their own tea.

Moving with Awareness & Care

How did people respond?

Everyone was very excited. Many had tried matcha before as matcha is widely available in Los Angeles, and people can buy bamboo whisks and scoops, but they rarely have the opportunity to learn the practice.

I told them from the beginning, “For the second serving, you will make your own tea.” When it was time, I asked them to take a deep breath, focus on their movements, and prepare the tea with intention.

My impression is that life is busy in Los Angeles: at first, many participants whisked quickly and rushed through the process. I said “slowly, slowly,” many times, reminding them to move with awareness and care.

Many people found it valuable and refreshing to dedicate time to making tea for themselves, when it was normal to just rush through their mornings.

Since starting tea practice at 25, have you noticed any personal changes?

I think my understanding of seasonal events and manners deepened: the knowledge has sunk deeper than conceptual level and now in my visceral level.

I love being outgoing and active, but tea requires discipline and structure. And if my movements are awkward or distracting, it takes away from the experience of the tea itself.

The best tea ceremony is one where the host’s movements are smooth and effortless.

Practicing the formal movements every week has naturally instilled a sense of grace and mindfulness in me.

It has also taught me to anticipate guests’ needs and how to create a welcoming atmosphere—something that has become second nature.

Passing On What I Have Learned

Tea culture is deeply tied to the spirit of hospitality, isn’t it?

Yes. For example, when I’m served a delicious meal, I express my joy straightaway: I think it’d make my host the happiest if the appreciation was communicated on the spot. It’s about being mindful of how and when to communicate in consideration for others. A way of hospitality that I’ve learnt from practicing tea.

The wisdom of tea which is very applicable to modern life.

Yes, absolutely.

I noticed a connection between the Shinto teachings and the spirit of tea. Do you have any plans for integrating both in the future?

My husband is a woodworker, specialized in a traditional technique called wood joinery. As a craftsman, he is deeply committed to preserving and passing down the traditional techniques.

I, on the other hand, have dedicated myself to studying Shinto and the tea. I believe my role is to share the cultural aspects of Japanese life—Shinto and tea—through storytelling and practice. Simply preserving techniques isn’t enough if they don’t remain relevant in daily life. These skills emerged from the necessity, from the way people lived, so they must be passed down together with their cultural living context.

I’ve also started studying folklores, which is about keeping the record of people’s everyday life. Shinto has always been close to everyday people’s life, and the tea practice is also born of culture that surrounds everyday life of people.

Together, my husband and I aim to preserve and pass on these traditions in a contemporary, living context to future generations.

A Quiet Beauty

The shrine we visited together today, I heard there are barely ten active parishioners, yet the shrine path was beautifully maintained.

Right now, it’s mostly those in their seventies and eighties who continue to uphold these practices because they were raised to believe it was simply the way things should be. But people of our generation and younger rarely participate. Without that sense of duty or connection, these traditions will eventually fade away.

Ideally, I’d love to see them preserved. As I feel the culture is the home where people come back to. Once it’s lost, we lose our spiritual home.

Where do you find beauty in your everyday life?

One moment that stands out is when I sweep fallen leaves. Leaves that have just fallen are soft, glossy, and fresh. But after a day, they become dry, brittle, and begin to curl inward. Their color fades, yet even in that decay, there is a quiet beauty.

The leaves that fell after I swept yesterday and the ones that fell this morning—they capture the passage of time in their own subtle way. The transition from life to stillness, from vibrancy to fading hues, is a reminder that everything in nature exists within this delicate cycle.

I also find myself mesmerized by the beautiful white feather of my bird, Bun san. It’s truly beautiful.