Close to Everyday Life

How did you discover the world of sento mural painting?

I studied modern art history in university, majoring in Japanese art and how to interpret it. There the focus was on how to look rather than how to draw. I became fascinated by how sento paintings were so close to the everyday life of everyday people, so I decided to do my graduation thesis on the mural paintings in public bathhouses.

It was then that I met my master, Morio Nakajima. He was about 60 years old at the time. There was a space in Odaiba which was made to look like a townscape from the 20th century, and he was demonstrating a live painting on a small board, something like 2 meters long.

I was surprised to see how the painting was changing second by second. The way he painted one or two pictures so quickly, without any hesitation and he did everything so cheerfully. He was a master craftsman of drawing. I was captivated and admired his work.

Seeing the Movement

Did you intentionally pick the occasion where you could see Mr Nakajima’s works?

That’s right. I was going around different bathhouses as part of my research, and beginning to understand the differences in the touch of brushes by each painter. Back then there were only three painters.

There was one painter named Mr Maruyama. He uses very deep colors. When I look at his work, I feel calm. He paints with quiet brushstrokes. Another master painter called Mr Hayakawa had a very powerful style of painting that made me feel energized when I saw them.

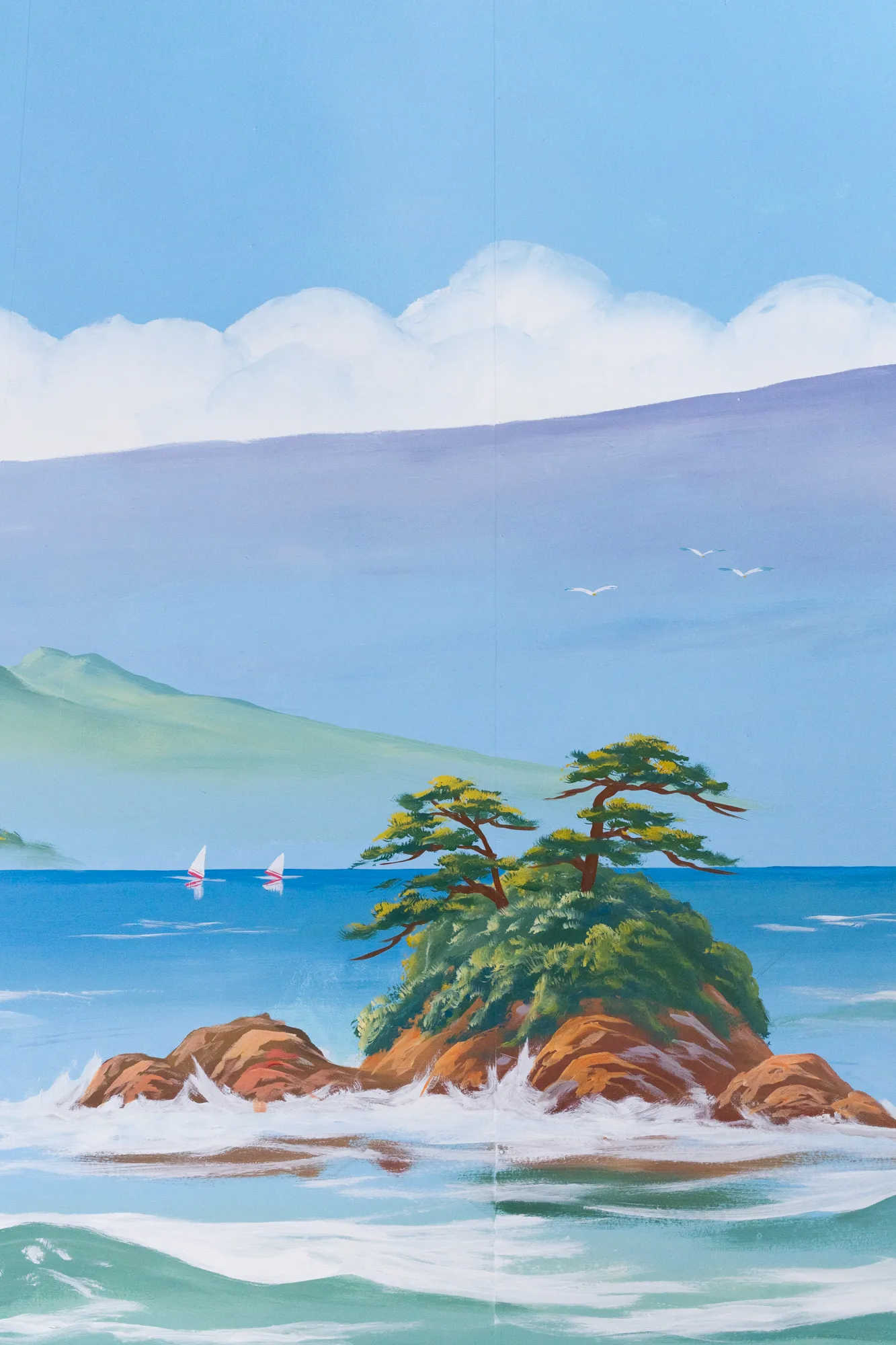

Mr Nakajima, my master, used bright colors, with a very rhythmical touch. He could capture lights reflected on the grass, and it was almost like I could see the movement. His drawing and bright colors always made me feel cheerful and uplifted at the end of the day at the bathhouse.

The colors and touches used by each painter are different, and when you look at a painting, you can tell that it was painted by THAT person.

Are all these masters still active?

No, all of them have advanced in age. So right now it is just my mentor, Mr Nakajima, and I who are carrying the load.

Becoming an Apprentice

When you met Mr. Nakajima, did you ask him for an apprenticeship right away?

At first, I simply wanted to see the production site for my research. I wasn’t interested in becoming an apprentice. I visited the production site several times for research. From those experiences, I thought it would be nice if this precious craft continued for the next 100 years. But there weren’t many sento painters anymore. So I applied myself.

Did he accept you as an apprentice immediately?

No, I was turned down because there were fewer and fewer painting works. So they stopped taking apprentices. However, I felt very strongly that I can’t just let this art disappear. Although the economy surrounding sento was not looking bright at that time, I thought there must be a way to make a living through apprenticeship, if I took multiple jobs. I went back to him several times asking him to teach me. In the end, he said yes.

But there was one condition: he told me that I should have another job because there was a high possibility that I wouldn’t be able to make a living only by painting. So I had other part-time jobs while continuing my apprenticeship.

“Stealing” the Technique

How was the learning process?

His way of teaching may be unique to Japanese craftspeople: it’s not like a school where a teacher takes you by the hand. He wouldn’t tell me anything to describe what he was doing, and I had to “steal” the technique by watching.

One day, he suddenly told me to try painting an island or a pine tree. I tried my best, but I wasn’t sure as it was my first time. The master would correct my painting by drawing on top. He said, “you did fine,” but the painting turned out to be completely different after his correction (laugh) .

Seeing his amendments helped me realize how I could have drawn better, I started seeing small details and techniques that I wasn’t paying attention to before. I continued to “steal” the techniques by carefully looking.

How long did it take you to achieve the level where you could become independent?

I continued the apprenticeship for about nine to ten years. At first, I just painted the sky. Then I was allowed to paint some clouds, and then some distant pine trees and distant islands. Gradually I moved on to painting larger and closer objects, and finally, Mt. Fuji. After that, I was given permission to paint either the men’s or women’s side of the wall. Eventually, I was told to paint a whole wall.

However, I consider myself still in a period of training. While I’m in my 40s, I try to paint what I think should be there, even if that decision will make my work more demanding.

Craftsperson or Artist?

As a sento mural painter, do you consider yourself a craftsperson or an artist?

To be honest, I don’t really know what this sento painting is. Since it is so integral to the daily lives of ordinary people, it isn’t something to be looked at in a formal manner. Regular users may or may not notice when the painting has changed, but some do pay close attention to it and enjoy it. It’s a very unique way for an art piece to exist, casual and vague. I still don’t understand this art completely.

I try to be a craftsperson for the most part. Artists, to me, come up with concepts and create their own works, but I take requests from clients and fit my work within the frame of requests as well as the surroundings. I think that is the way to paint as a craftsperson.

There are some aspects that I cannot clearly determine which is which. In the end, I let other people make the decision, rather than deciding for myself.

Do you ever feel self-conscious about being the first female sento mural painter, on top of being one of the two remaining?

I‘ve been lucky in that the sento bathhouse culture has recently come back and been taking off along with the general retro revival.

As was the case with me, in many areas of crafts they have stopped taking apprenticeships, but the number of female craftspeople is increasing recently. I think one of the reasons why women had a better chance of being accepted was that they weren’t expected to make a living for the entire household.

Although in the end, I believe what it comes down to is having the determination to become a craftsperson.

A Sense of Familiarity

You’ve now been in this craft for over 20 years.

How do you envision the future of sento public bathhouses?

Unlike in the past, many families now have baths at home. The very act of going out of your way to take a bath is no longer a necessity, but rather leisure. Sento will be a place to refresh your mind, almost like popping out to a nearby coffee shop.

I want to contribute to a culture that makes people more familiar with public baths. It’s a place where conversation and friendship naturally start and grow. When you keep going to the same sento, you’ll start seeing familiar faces.

“If you come at this time, you can meet that person” or “I don’t see her much lately…, so let’s go see how she’s doing,” etc… these are all common conversations to be heard in sento. That’s how the community builds.

I hope that more people from different generations will become familiar with public baths and its culture in the future. I want my painting to become a conversation starter. That’s why I also insert small tidbits to look out for. “Ah, the color of Fuji has changed”, or something like that.

What is beautiful to you, Mizuki?

As a sento painter I don’t necessarily strive to paint something beautiful. Instead, I aspire to paint something the viewers feel close to or familiar with, even though they’ve never seen the painting before. A sense of familiarity is what I’d like to achieve.

As for beauty on a more personal level… After I gave birth to my son, I began to look at insects, grass, and other living things more closely with him. I started seeing the lines that these grasses or flowers consist of. The beauty of these lines struck me.

I only started realizing how beautiful they were after all this time I spent on the earth. These lines of living things captivate me.

Interview with sento culture expert Stephanie Crohin:

Accepting Others and Self

What do you feel is behind the recent resurgence of sento among younger generations?

Stephanie Crohin: For younger generations, the sento serves several purposes, one of which is education and learning to share a space with others. It instills the value of yuzuriai (譲り合い), which can be translated as sharing, compromise, and mutual respect. This value typically tends to fade in big cities where people no longer pay attention to others in the community.

It also teaches children how to behave around people outside their family in a still very intimate setting. I’m convinced that these cross-generational interactions can be significant in a child’s development.

I’d also add that the sento plays a role in body acceptance. In a world where we’re constantly judged on our appearance, compared to others, and bombarded with standards, the sento represents reality and kindness. Everyone is different, everyone has their own body, but there’s no judgment or discomfort in these places. It contributes to body positivity in this sense.

Finally, in our modern societies glued to screens and burdened by work, the sento offers a break, a detox, a moment where we disconnect from our screens and worries. It has the power to soothe the mind, immersing us in well-being in a steam-filled environment, with the sound of buckets, splashing water, and gentle voices that can lull you into a meditative state if you allow yourself to fully relax.

Visiting the sento is both physical and mental care, and for many, it’s a genuine lifestyle.

The Heart of Neighborhood Life

What role did sento play within local communities in the past?

In the past, sento were at the very heart of neighborhood life, an essential part of the majority of residents’ daily routines. Since many homes didn’t have bathrooms in the first half of the twentieth century, both the rice merchant and the bathhouse were central to every neighborhood.

There was even an ecological cycle between the two—at the rice merchant, they removed the rice husk, which is astringent and was used as soap at the time. Rice bran was distributed at the entrance of the bathhouse for bathers to wash themselves with. In fact, some still use it today and at some traditional rice merchants you can find small bags of “nuka” (rice bran powder) sold at a very low price. I sometimes buy some before going to the sento to use as a body scrub.

Sento were therefore essential for daily hygiene but also served as a social hub for neighbors.

What role do they continue to play despite their decline in numbers over the past years?

Nowadays, most homes have bathrooms, so personal hygiene is no longer the primary motivation for bathers. However, the sento remains a vital and important place for many local residents.

Firstly, it is very practical and reassuring for elderly people, especially those living alone. You may have heard about the alarming number of deaths in Japan each year due to thermal shock in winter amongst the elderly, often occurring in home bathrooms. Sento help prevent such accidents.

In addition, many people are socially isolated at home. Going to the sento allows them to maintain a social life with neighbors who also visit. I worked for six years at the reception of a sento, and I deeply felt the humanity that emanates from these places and how crucial it is for these people to visit the sento—both physically, emotionally, and psychologically.

How do you see the future of sento?

It’s inevitable that more sento will disappear, unfortunately. The reason is simple—it’s a very demanding job, requiring a lot of energy and time, but in most cases, it doesn’t bring in financial rewards that match the level of sacrifice.

However, I believe that sento culture, a true Japanese treasure, will endure, and many passionate people will continue fighting for their preservation. This includes many younger generations too. Like Mizuki san.

Representing the Future

How would you describe Mizuki’s painting style?

Mizuki san’s paintings are bright and cheerful.

When you step into the bathhouse, the first thing you notice is the light radiating from the painting, which often has a calming effect, and the vibrant yet soft colors that bring a lot of joy. I also love spotting Mizuki san’s personal touches in these paintings that reference the local culture or the family running the sento.

What makes Mizuki special in your eyes?

I greatly admire Mizuki for her unique work and her perseverance throughout her journey. She has found profound meaning in her work, balancing her passion for it with what she contributes to all these establishments.

As a sento user and someone sensitive to art and interiors (being an interior designer), I personally enjoy being able to appreciate her beautiful paintings while bathing.

Mizuki san represents the future of this precious work, and thanks to her, it will continue and gain more recognition.

Stephanie Crohin has been living in Japan since 2008 and quickly became fascinated by Japanese bathing culture, specializing in this unique field. She is a recognized expert, official sento ambassador, and has written three books about sento in Japanese and French.

Stephanie is also a member of the Tokyo Municipal Bath Committees and contributes to the annual evaluation of sento. To date, she has visited over 1000 Japanese public baths across the country.