Wisdom in the Region

You were born and raised in Nagasaki, a coastal city on the Southern island of Kyushu. It’s famous for its stunning nature, strong craft tradition, as well as being a historic point of exchange with the outside world and other cultures.

How did growing up there influence your work and your outlook on life?

Looking back, I realize it has influenced me and my work in many ways.

Now that I am working on re-introducing Japan and the Japanese art of living in a contemporary and international context, I realize a lot of what I do can be traced back to then. My childhood experience from Nagasaki.

There were oceans, mountains, and rivers all around. There were even three kinds of oceans to choose from and as a child I had access to all of these by bicycle or simply by walking. Nature was rich and abundant. The food, naturally, was fresh and delicious. This inspired a fondness and reverence for nature and its ever changing beauty in me.

Some of Japan’s leading pottery centers like Arita and Hasami were always nearby, and I had been going to Ureshino tea practice since I was a child. So closeness to craftsmanship and cultural practices were also an integral part of me growing up there.

Historically, Nagasaki is the gateway to culture from the west. During the period of national isolation in Edo, Nagasaki was actually the only port for trading. That cultivated a unique openness to other cultures and the merging of cultures from the West and the East.

It’s not like my ancestors actually did that kind of work. But rather, I think there was such wisdom in the region that became imprinted in me and that forms the basis of what I am trying to realize through my work.

What made you leave Nagasaki?

A Moment of Profound Clarity

I had always yearned for the city. Maybe it was because I was from Nagasaki, but I was always curious. Ever since I was a child, I knew that I wanted to go to Tokyo and live in the city.

I wanted to open my own restaurant. I didn’t know what it was for at the time, but I just had this strong drive and conviction in me to open my own store to create a unique space and experience. So I studied interior design and architecture. All of that was for me to build my own store. It’s not like I ever wanted to be an architect.

Soon after I moved to Tokyo, I began to visit New York and Paris. I wanted to see even more of the city. Not just in Japan but also internationally. I followed what stimulated me more and more. It was almost like a kind of addiction.

What made you refocus on Japan eventually?

At the time in the 80’s, the newness and energy of New York was incomparable to Tokyo. I went abroad to gain inspiration, and kept on going back for several years, but eventually I realized that the excitement of those foreign cities was not the core of what I was seeking on a deeper level. On the contrary, I realized that the quality that I found permeating so many aspects of Japanese culture was really high. And that this quality or sensibility resonated profoundly with the core of what I valued in life.

I actually remember that moment of realization quite well… It almost felt like something came down to me, a moment of profound clarity. I was looking at my Japanese passport and I thought to myself, “Ah, OK, it was Japan.” I realized that what I was pursuing all this time was inside of me after all, and that was it.

It began to dawn on me that Japan could become a way of being, both with a strong identity but also open to hybridization. I intuited that exploring and reinterpreting the forms of everyday life emanating from Japanese traditions could provide future generations with new means to live a fulfilling life, regardless of where we are. I have been in pursuit of expressing and conveying that vision ever since.

Attention to Details

Japan has this hard to define quality that I believe you are alluding to, and that almost everyone who has been there can relate to and appreciates. This sense of care that’s apparent in small things, like customer service or the way items are packaged. It’s also palpable in all your products, spaces and experiences.

What do you think that quality is?

I believe that quality is actually the national characteristic of Japan. A characteristic that is rooted directly in our appreciation of nature and our enduring belief in preserving and cherishing it. This concept is closely related to Shinto.

It’s something Japan is good at, paying attention to details, focusing on getting the little things right. It’s this sensitivity to detail that allows us to make an effortless shift towards focusing on the big picture as well. On the other hand, giving the big picture a once-over is hardly enough to see all the little details.

Do you think the Japanese sensitivity to details is a result of the Shinto tradition of nature worship?

Absolutely.

It’s related to noticing minor shifts, being sensitive to the subtle changes of seasons.

Though I would not call myself a Shintoist, I do visit the local shrine on New Year and Obon. And many Shinto traditions are still prevalent in Japan. For example, ancestor worship and the worship of sacred mountains. It amazes me that many Japanese people still retain this divine belief in their ancestors and in nature.

There used to be many similar beliefs in the world, like sun-worship, but Japan is one of the few places where it still exists as an active force in its contemporary culture. There are still over 80.000 shrines spread across Japan. That’s even more than convenience stores!

Reverence for Nature

Even if we at times import cultural and religious concepts from other countries, I feel that nature always prevails as the foundation and focal point of our culture. We can mix and match concepts, yet the reverence for nature remains at the core of our beliefs. Even Buddhism has morphed into our own tradition after it arrived in Japan from China, Korea and Tibet.

Shinto and nature worship was the central faith before all these other concepts made their entry into Japan, and so they’re always viewed through that lens.

Which Japanese values do you want to convey through your work?

It’s impossible to pick bits and pieces to showcase. Instead, my aim is to create a multi-faceted experience that is imbued with these key values, but expresses them as one whole. It has taken me 20 years to come up with this. From when I started in Japan to the founding of OGATA Paris in 2019.

A meal in a restaurant is far from sufficient to fully convey my message. I had to expand the experience to the tools that are used in conjunction with the food, to the tea and the sweets we serve. Only when all elements come together can we fully convey the Japanese values. As they say, seeing is believing. We can’t only talk about these values, we have to let people experience them first hand.

OGATA Paris is the place where I can create this experience. I have always wanted to create a place like this, and the idea developed, little by little, until it gained shape. I chose Paris as the location for this ideal to go out into the world, because of its rich cultural history, as well as an international community with an appreciation and understanding of art, food and culture.

A Window into the Japanese Way of Life

The great thing about an experience is that people are free to give it their own interpretation based on what they feel, what made an impression on them and how they wish to bring this into their daily lives.

That’s right. That’s something I talk about a lot, it’s an ever-evolving process, it’s not bound by rules. We simply give people a place to start.

The world is only just coming to understand the ways in which capitalism has led us to destroy nature. The ways in which it cuts us off from our connection to and reverence for nature, as well as our appreciation for natural, handmade things and experiences. I believe this impoverishes our way of being and that this is something many people around the world are waking up to.

At this point in time, I believe Japan can become an important philosophical and experiential resource for the rest of the world. Our traditional knowledge has the potential to help solve these ongoing issues. Especially if we succeed in allowing that traditional knowledge to take contemporary shapes and forms. This is the very core of my work and my mission in life.

Not that I’m telling everyone to behave like the Japanese. Quite the opposite. All I’m doing is offering a window into the Japanese way of life, and asking that they consider what it could mean for them, with the hope that it will lead to their own cultural shifts. Japan is nothing more than a starting point for those shifts.

Reinventing Tradition

You have described this with the word, youshiki (様式), or way of being in English. Could you expand upon it?

It’s a way of life. The space I spoke about creating earlier is part of this as well. It’s not just about the food, it’s a combination of that component with many others: cutlery, tea, sweets.

All these facets combined invite us to feel and behave in certain ways, in Japanese this is called sahou (作法). The implicit rules or set of manners that when we follow and practice them shape our behavior and feeling.

These sahou or rules that guide our behavior are quite explicit in many traditional Japanese arts, like in chadou (茶道), the tea ceremony.

Chadou was created by our ancestors to share the beauty of a certain lifestyle. My work is not to further promote the tea ceremony in its traditional form, but instead to translate and elevate this concept to a way of life that can be easily shared and understood by people all over the world. To reinvent and adapt traditional sahou to contemporary life, so they can inspire and inform new, harmonious ways of being that can be easily implemented across the world.

All that people know right now is the traditional Japanese tea ceremony as it’s been refined and preserved by different traditionals schools over the centuries. It’s not a way of drinking tea that has been more widely accepted across the globe. It’s a wonderful subject to study, but I aspire to take this concept further, to translate it into our current modern world. That is what I call the Way Of Being. Something that can be used by everyone.

Creating A Common Language

That’s why I founded OGATA Paris. It’s not a typical Japanese restaurant, people probably have a hard time pinning down exactly what the cultural background for it is. Is it Japanese? Is it Oriental? I want people to consider exactly what the style is of this restaurant that appeared out of nowhere in Paris, to find out for themselves whether they like it or not. There will always be people who like it, and there will always be people who hate it. Those who do like it can take their impressions back home with them, let the style of the restaurant inspire them. That is A Way Of Being.

Japan has been attracting attention lately, but it’s still viewed as a mysterious, unknown country by many. I want to create a common language to bridge this barrier, as I’m convinced Japan has an important role to play on the world stage.

The spaces you create have a familiar atmosphere, one that is in tune with nature. It shows the time that was spent building it up. Entering them we feel settled and enlivened at the same time.

How do you create such spaces and atmospheres?

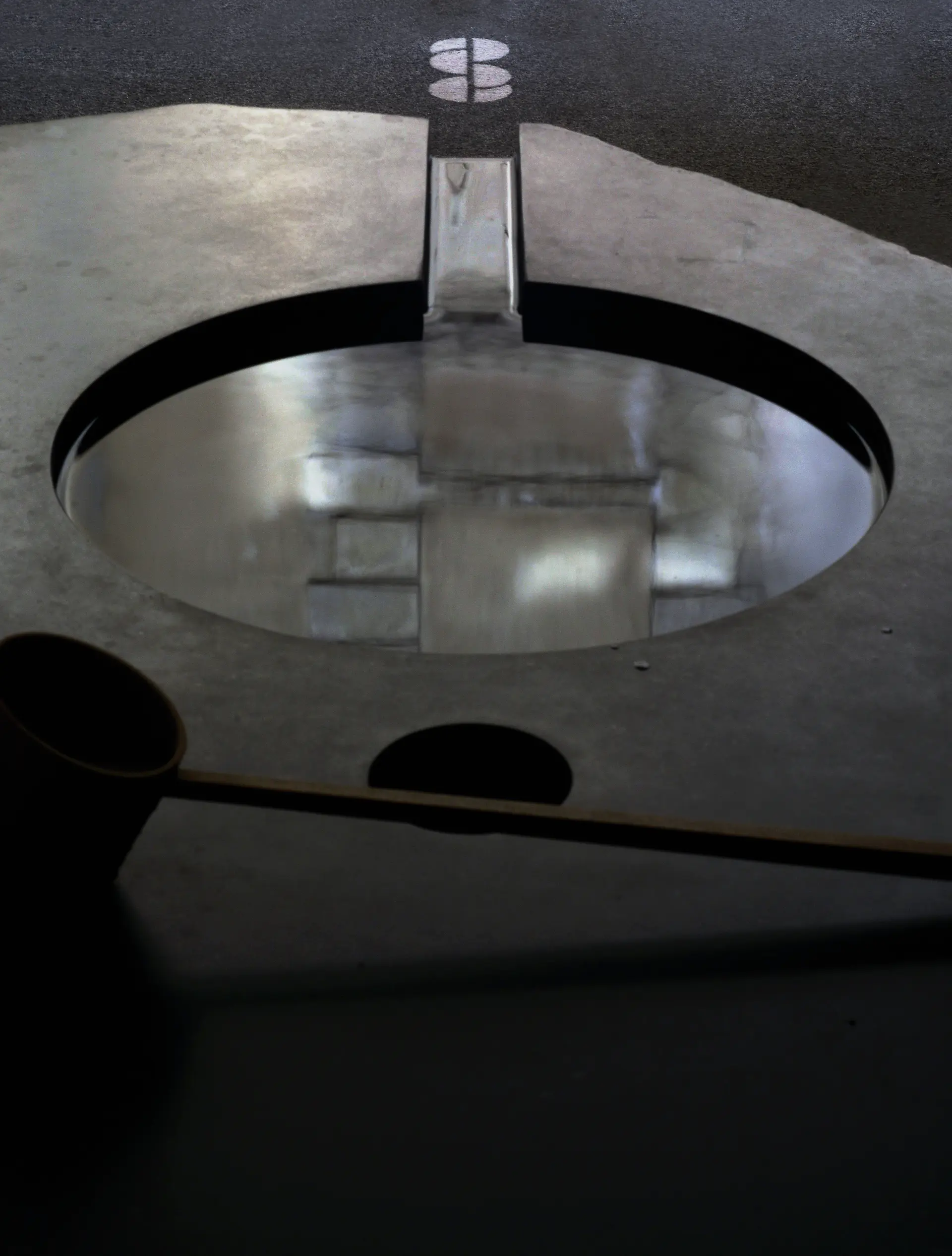

My work is a constant dialogue with nature and the different forms it has given rise to. So nature is always the main theme I focus on. I always make sure there is nature in the background, even when there isn’t actually any present in the vicinity.

In Japan, there is a custom of creating the atmosphere of nature where there is none – we call this mitate (見立て). An example would be to use a rock in your garden to exemplify Mount Fuji. Bringing subtle nature or natural elements into the space in this way, like rocks, flowers, etc., evokes a sense of nature that is vital to the kind of atmosphere I want to create.I’m also always conscious of what is around me, and how it resonates with the space I’m creating. For example, integrating the view through a window onto a beautiful adjoining old wall into my vision of the space and the overall harmony and tension. This use of the surroundings in the creation of a space, shakkei (借景), played a large role in the design of my restaurant in Paris.

Opposing Forces & Atmosphere

The other vital component is the materials used in construction. I make sure to use natural materials in the restaurant. There is a certain power, an energy, that you feel from the earth, something that is not present in plastic. The use of these materials reverberates with the people in the room, it can make them feel calmer. I pay close attention to the aura of the materials I work with.

Last but not least, I look at balance, at how to pitch opposing forces together to create a whole: large and small spaces, long and short, tall and low. It’s the same principle as with light: a well-lit room will look even brighter if you have just come in from the dark. The stronger these opposite forces are, the easier they are for people to appreciate. I manipulate the space to allow them to experience these opposites.

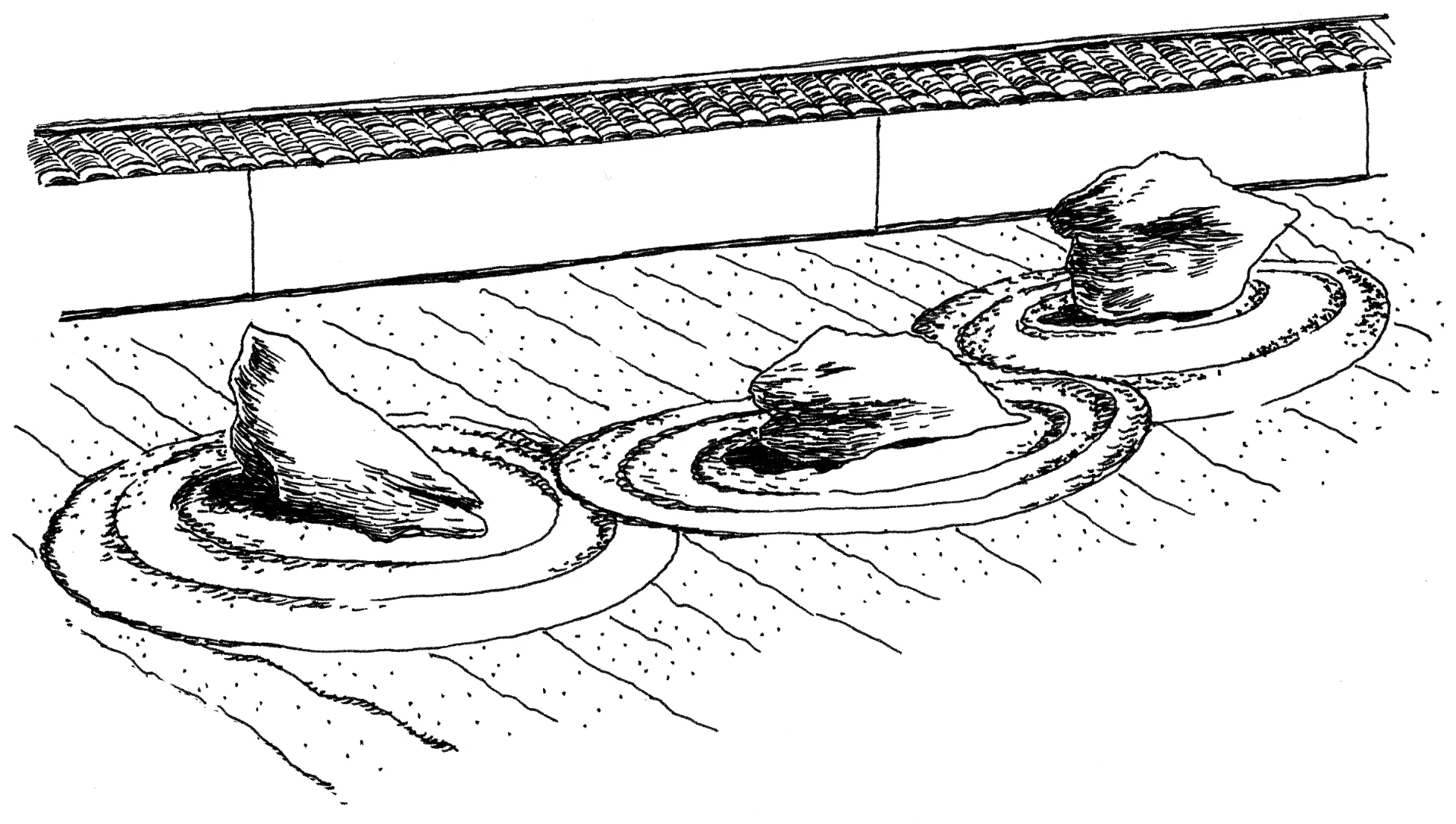

You see this at work in the architecture of shrines, too. There are no gods hanging out in those shrines (laughs). But somehow you can feel their presence nevertheless. This is because of the atmosphere in the shrines. It starts from the torii gate at the entrance, the threshold to a separate world, which people must cross to enter the shrine.

Then there are the hedges that adorn the grounds, and after many steps, you arrive at the temple where the divinity is said to reside – a divinity you are never allowed to see. The offering box is placed on a step below the entrance to the temple, and that is as far as visitors can go. Anything beyond that point belongs to the gods.

A Timeless Way of Being

If you were to enter this forbidden space, you would find it empty, but the setting suggests that this is where the gods reside. During prayer, you call the gods to your aid, make your request, and leave without ever crossing this final barrier. The temple is like a second home for the gods, a place where they can descend upon to interact with us, and we feel like they are there because of how the temple is designed. I learned a lot from studying the architecture of temples and shrines.

What does beauty mean to you?

Something that breathes authenticity, truth and honesty. Something that is free of lies. There is no room for lies in beauty. This is the beauty I always strive towards.

What role do you see for yourself in the future, what is it you would like to achieve?

I’m not too concerned about myself as a person. It’s far more important for me that I create an educational method. That can be my legacy. That means a lot more to me than my own place in the world, than any fame. Everything I have built up until now, from ways of serving tea to cooking, to design, all of this is part of an educational method. The next phase will be focused on how to communicate it with the world.

I truly believe that I was put in this world to achieve this. I can’t fully explain it myself. It’s like I’m being moved by something.

What message would you like to give to the readers of this interview?

My goal is to reinvent the Japanese art of living and create a timeless way of being out of it that can inspire a contemporary global audience. Something they can experience, experiment with and adapt to live a more balanced and spiritually rich life for themselves. I aim to create a way of living, regardless of the shape it may take.

The best message I can give to you is to discover your own way of being.

And this way of being doesn’t have to be Japanese.

Precisely.

Japan is only a starting point. Every country has its own way of coexisting harmoniously with nature. A way of being is boundless, it resonates everywhere.