Seeking Ineffable Beauty

Everett, you had a near-death experience at the age of three.

Can you tell us what happened and how that impacted you?

I was with my father on this beautiful lake deep in a forest of western North Carolina. We were on a canoe and the canoe capsized, and I remember sinking down into the cold and green and murky water, and looking up at the surface and seeing the sunlight going through the green water. It was so beautiful.

That moment was my first encounter of really being aware that I was alive and, at the same time, my first awareness of ineffable beauty. It only lasted a few seconds. Very quickly, my father reached down and pulled me back up to the surface. Part of me didn’t want to come back. I wanted to stay down there and to enjoy that exquisite beauty, with the coldness on my skin and the light coming into my eyes in such a radiant way.

I really think that experience has guided my life ever since. It was the start of this journey for seeking out ineffable beauty and recording it as best I can.

Could you say more?

When we encounter ineffable beauty, we lose ourselves. It’s kind of a death experience. This, I think, has really drawn me toward finding ways that I can recreate this experience of losing myself.

It’s a little death, but at the same time, it’s a great acknowledgement of being fully alive. I think that’s why it’s really difficult for me to say that I have an occupation, because I think my whole life has just been formed around this conversation with beauty and the ineffable.

Jumping Into the Unknown

You have been living in Japan for 35 years now, capturing its deeper layers through your photographic works and writing.

Could you describe your experience upon arriving here?

I arrived in Japan in early April of 1989. The night before I departed for Japan, I was in Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. I was going to the City Lights Bookstore to pick up some books to take with me to Japan and I happened to run into the American poet, Robert Bly, who I had met before on a few occasions. He remembered me and I told him that I was going to Japan. He said, “Wait. There’s somebody that I want you to meet.”

A few minutes later, an American Zen Buddhist nun from the San Francisco Zen Center arrived. Robert told her that I was departing for Japan and he asked her if she could give me some advice. I was expecting her to say, “Oh, you must go to this temple in Kyoto or Kamakura,” but no. What she said was, “When you arrive in Tokyo, don’t stay in the city. Catch the first train you can out to some fishing village. Stay there a few days, until you get over your jet lag and then follow your intuition.”

It was an amazing thing to say.

I knew about Osorezan, which in English is translated as fearful mountain. It’s the place where the Itako shaman women gathered to talk with the dead and that became my destination. My first full day in Japan was on Osore mountain and it was a step back into time.

You skipped all the neon lights and went straight into the deep mountain.

Looking at my life in Japan, it feels like a constant calling, a constant jumping into the unknown. That first adventure to Osorezan really influenced the course of my life!

When I was there, the shamans were not there. They come in the summertime, but I got that information and I went back a few months later and I met them, and they invited me to stay with them in their hut. They spoke a very, very thick local dialect and my Japanese wasn’t very good at the time, and it was quite challenging to understand them, but on a visceral level, on an instinctive level, we had amazing nonverbal conversations.

Dissolving the Ego

At night, there was an open hot spring on the mountain and we would go out there and go into the bath together. For a young 22-year-old guy to be in the bath with these 70- and 80-year-old women was [laughs] an eye-opening experience, but it was also a heart-opening experience. It gave me the sense of a shared humanity and I learned so much from them because these women grew up in a pre-modern Japan. They were from a very rural area. Most of them were born in the Meiji period, around the turn of the century, and they were communicating with the dead. For them, the veil between the visible and the invisible worlds was very, very thin. This, in a way, became my passion for Japan, to explore both sides of the veil.

I went to Osorezan every year for about six years and would spend the summers with them. I learned how they trained to open up their spiritual eye. They would go through very austere training in the wintertime, waking up at 3:00 a.m. and praying under cold water.

I saw that this was a way to dissolve the ego, to break through this crystallization of ideas and thoughts and feelings that limit our experience of the world. This got me inspired to begin doing waterfall meditation and I found that it was very effective to seek more clarity, a kind of hyper-clarity, one could say, so I would become more aware of things that are usually not apparent to the five senses.

Did you always think, as a teenager, that you had a strong sense of ego that was getting in the way or limiting you in one way or the other?

We’re all unique. We come into this world with our own unique bodies and ways of thinking. Growing up, I had a learning disability and speech impediment and terrible awkwardness, a shyness, a feeling that I just didn’t quite fit into society, so social situations were very painful and they still can be, in a way.

This is the bind of the nervous system that I was given with this life and this is what I have to deal with. It’s been a lifelong struggle and an adventure to understand how to work with the ego, this body, and to find some kind of peace with the world.

Conveying the Spirit of a Place

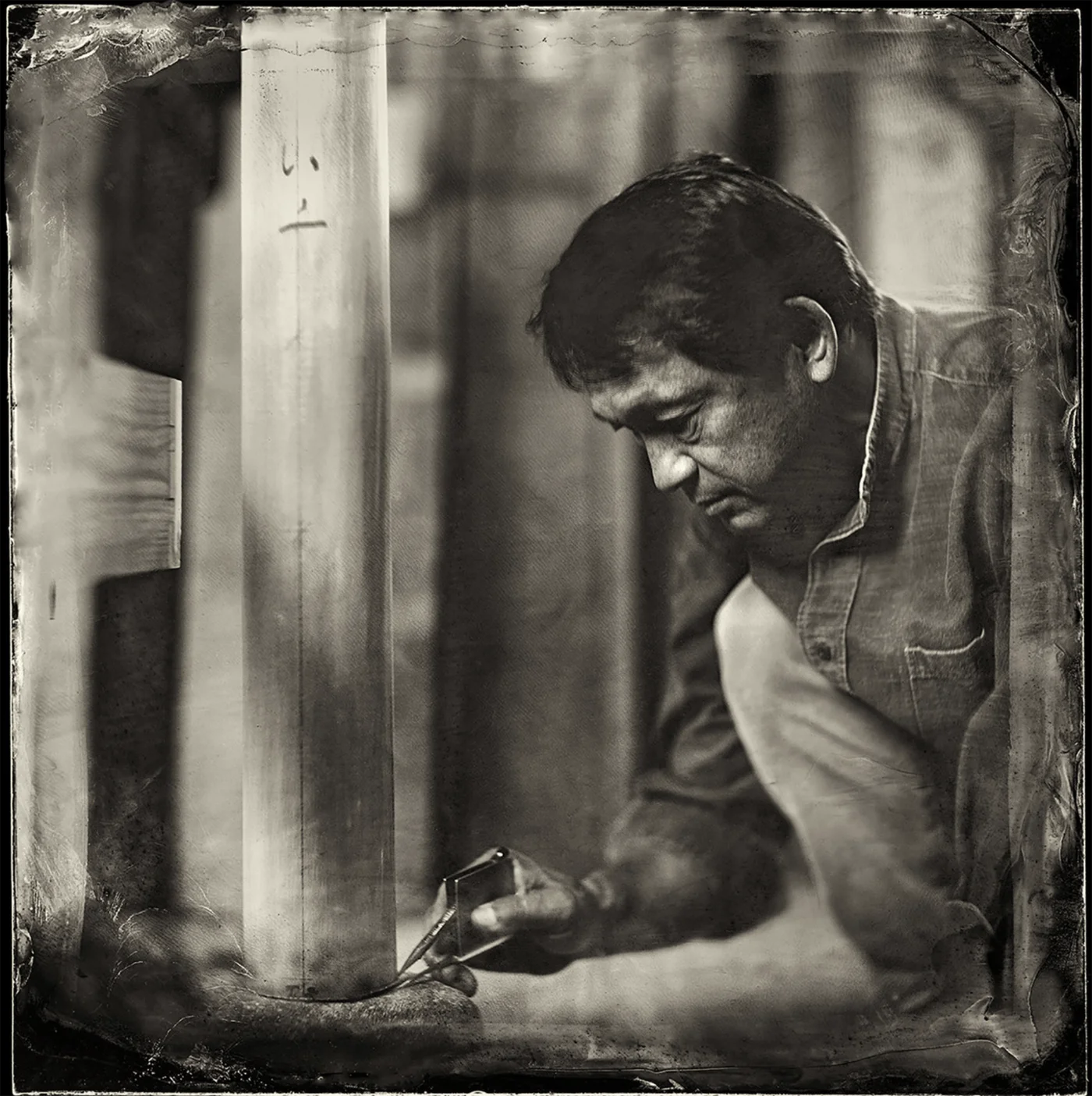

What inspired you to use collodion wet plate as your medium in photography?

Well, when I first went to Osorezan I would often stay in the Buddhist temple there, on the mountain, with the local men and women. They would spend their days praying, communicating with their deceased relatives. Then, at night, we would open up bottles of sake and eat and drink and dance and sing.

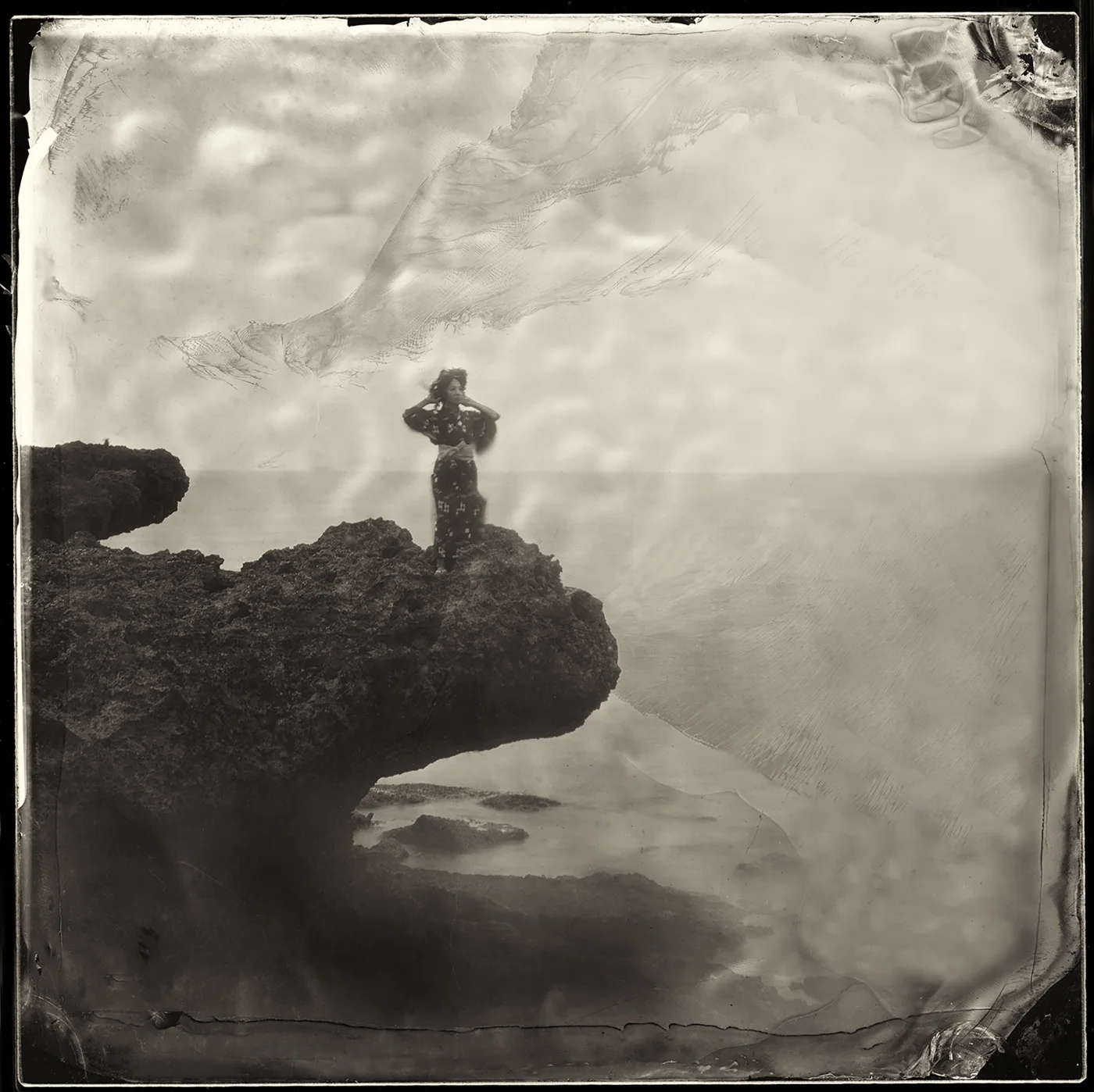

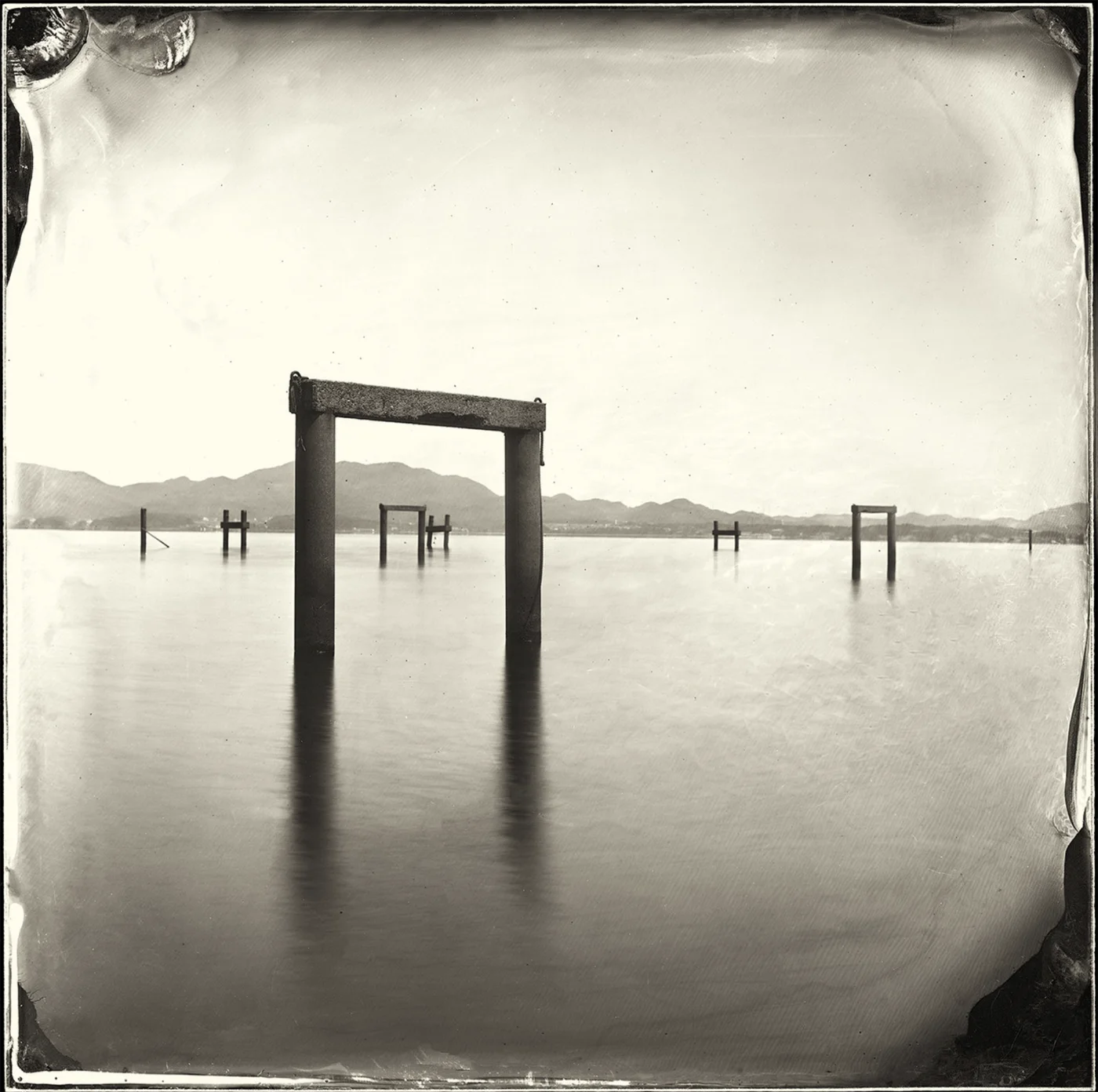

Being with them, I could feel the ambiance in the temple as well as the ambiance around the mountain, these places that emanated a distinct spiritual energy. As a photographer, I was always struggling to somehow convey that spirit of place in a photograph. I could never really do that with ordinary film, but when I started using the collodion wet plate negative process, I felt I was able to then begin to do that.

How does the actual process work?

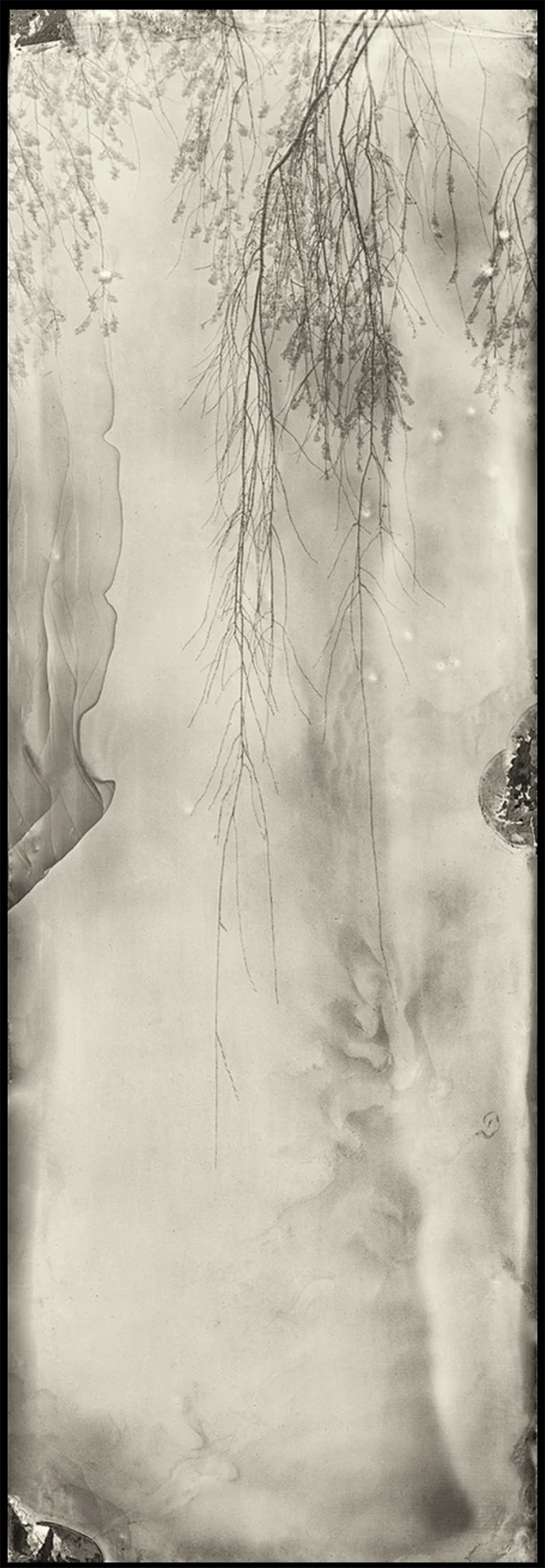

I make a glass negative on-site, where I photograph. I have a black darkroom tent with a red window in it and I make the negative in the tent. I’m using chemicals and different techniques to create each negative, and each negative is unique.

What I discovered is that it’s very much like pottery and the way a potter can use glazes to create certain landscapes on the surface of a pot. I found I could use these light-sensitive minerals and chemicals to create landscapes with the chemicals on the glass plates. I’ll even use local sake and I’ll put a little bit of the earth into the chemicals, so it’s very much a ceremonial process. It’s very much a way of bringing the landscape into the process and it becomes what I feel at the best moments is a collaborative experience.

What I found was the more I could empty myself, the more serendipity would happen and that these amazing chemical stains would create landscapes on the negatives.

Emptying Ourselves

What do you mean by emptying yourself?

The more that I can get my ego out of the image, out of the process of making the image, then serendipity happens. I think for a lot of photographers, they’re attempting to assert their vision through their images. I am actually trying to make photographs where there is no photographer. Some of my exposures can be very long – five minutes, 10 minutes, 15 minutes, even. When I make those long exposures, I’ll walk away from the camera and from the landscape.

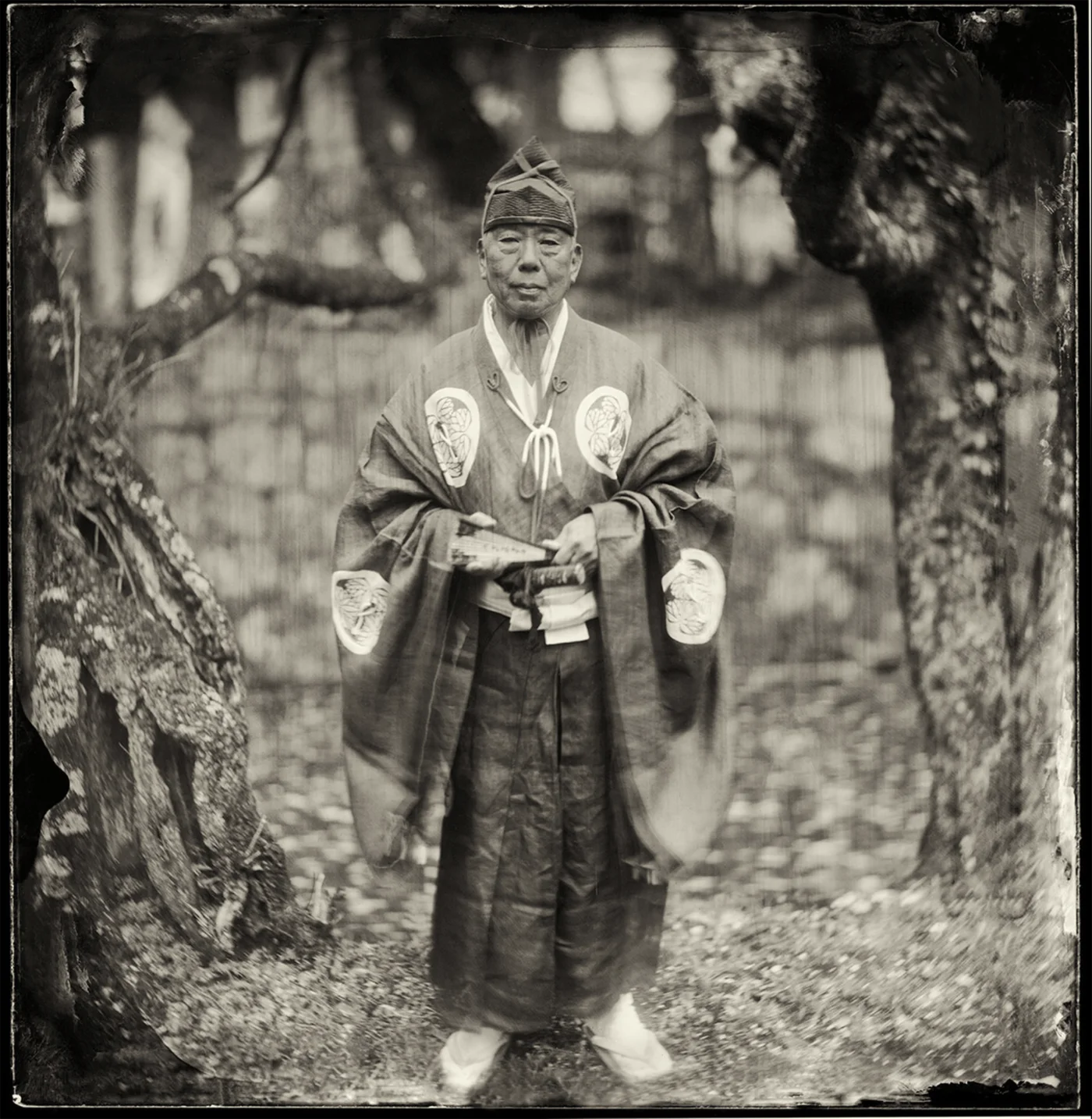

What we learned from quantum physics is that our consciousness influences our environment, so I really want to minimize that, so when I’m taking photographs of people, when I’m making portraits, I always have my back to the subject and I ask them to just nod when they’re ready for me to open the shutter.

I really want for the image to be a dialog between the subject and their portrait because most of the people that I photograph are people that have a clear destiny, people who should be remembered 100 or 200 years from now, whether they be artists or craftsmen or people from the ancient families in Japan. I’m doing this series of people from old Japanese families, some of whom can trace their ancestry back 35, 50, 75, even 120 generations, over 2,000 years.

It feels good to make these images and play a positive role in history, because when you really think about it, all of us are participating in the making of history. Most of us, unfortunately, are passive participants, but the reality is that we’re manifesting human history with our individual lives. Whether it’s our private history, our family history, or our community history, we are playing a role.

This is really what I feel from photographing these wonderful people. They’re very aware of their place in history. I feel that the more we can be aware of our place in the unfolding of history, we can live with a bit more vitality and purpose, a deeper purpose.

Self Power & Other Power

Hearing your process, it sounds very much like surrendering to other powers .What came to my mind are the two Japanese concepts of ‘Jiriki (自力)’, which is usually translated as self-reliance or self power, and ‘Tariki (他力)’ which translates as other power.

How would you describe your process in this regard?

I’m glad you brought up the subject of jiriki and tariki, because jiriki is Zen and a lot of people in the West, when they think of Japanese Buddhism, they think of Zen, but there’s also this beautiful world of tariki, that salvation is around. This is associated with Pure Land Buddhism. I really feel that, for the 21st century, for where we’re heading, it’s necessary to get away from self-absorption and to move toward realizing this interconnectedness that we have.

This is what physics is telling us, but because of the way we’re structured, we end up seeing ourselves as individuals, but it’s a fiction, so I have a lot of interest in this.

In the photographic process that I’ve created, I’m seeking a balance between jiriki and tariki, a balance between focusing on myself and then letting go to something greater than myself. To explain this, I can say that, in the preparation process, I see it very much as a meditation. There are a lot of details that demand my attention, making sure that the chemicals are in the right condition that I’m looking for, that everything is clean, the glass plates that will become negatives are clean. In this process, in order for things to go well, it really requires a lot of concentration to achieve success, but when everything is in order, then it’s a beautiful letting go.

I think, in a sense, the borderline between jiriki and tariki is when I decide upon the exposure because, with this process, I don’t use a light meter, but I choose the exposure with my senses, with my eyes, but more than my eyes, really, I’m asking myself, but I’m also listening to the wind, to the environment, what is the exposure? What is the correct exposure for this situation?

This is really where that crossover is, that balance occurs.

A Sense of Connectedness

I really feel that the art of living is having this delicate balance between jiriki and tariki, and I think the easiest way to see this is in a good marriage, in a good relationship. You have yourself, but you also have a partnership and you have someone that you can depend on at times and that they can depend on you. The beauty of a relationship is this dance, this interplay of self and other. I think that, when we have this, then it expands into a conversation with a broader community.

I mean, my partner and I, we just finished making a book on Umui, which is the spiritual heritage of the Okinawan people. We both really feel that this is really the reason that the island people are able to live so long, that they embrace the sense of Umui, the sense of interconnectedness with each other and also with nature.

It’s actually very similar to the Hawaiian indigenous people’s concept of aloha, which is not sufficiently talked about, this animistic sensibility. Of course, we get caught up in concepts when we start talking about these things and I was very much aware of this when I was writing the book and photographing the images for the book, but I feel that we were able to successfully convey this feeling in the project.

Also, with my photography, it’s a communication with light, sunlight. When we talk about the spirit of tariki, until recently it was very much a part of rural people’s lives in Japan. I’m just thinking of the phrase ‘otento sama’. When I first arrived in Japan, I could still meet old people that, every morning at sunrise, they would go outside and they would make a prayer to the rising sun. This expression, ‘otento sama’ basically it means the god sun. This is tariki, that we get our life from the sun, from the stars, from the universe. The more we feel this sense of connectedness, it can fill us with beautiful new energy.

Takumi: The Spirit of Craftsmanship

You have shared how you believe the concept of ‘Takumi (匠)’ is essential in understanding Japanese culture.

What is takumi and why do you think it’s so essential?

For years, I thought of takumi as just being craftsmanship. And then I was looking at Jomon pottery, the pottery that was made by the early indigenous people that lived in Japan. Scholars say that Jomon culture started somewhere 12 or 15,000 years ago and continued until around 300 BC. A lot of the pottery, there’s amazing craftsmanship that, at the time, you could find no other place in the world and it got me thinking. It’s like, you know, the pottery, it went from being functional to being ceremonial, but even in the functional pottery, there’s a care for detail of making something that could just be ordinary, to make it special, to make it beautiful. I feel that that’s really the origin of this spirit of takumi.

Then, about 15 years ago, I was photographing fashion in Harajuku and I saw this teenage girl’s cell phone and the way that she had decorated it so beautifully, with so many different beads, that she had, in a way, created her own little universe there on her phone. You could also say that she had breathed her soul into her phone, that it wasn’t just a phone, but it was an eruption of her identity, of her soul. It was connected with what the ancient Jomon potters were doing.

Then, a few years later, I had this commission to photograph carpentry tools from the Edo period, especially the carpenter’s plane that, when it’s being used, you cannot see the details of it, but the craftsmen who were making them, they were putting so much beauty and detail into something that people would not see. I thought, “This, this is takumi!” It’s not just for show, but it’s an expression of the craftsman’s soul.

Caring for Things That Go Unnoticed

That’s what got me thinking, is there the spirit of takumi in other parts of the world?

I thought about German craftsmen. I thought about the amazing French jewelry craftsmen as well as the Italian Stradivarius family that were able to really bring out the essence of their material and to breathe their soul into their work, so I feel that it’s something that is universal. It’s rare, but for various reasons, it has become amplified here in Japan. We can see it in many craftsmen of different genres, in their work.

Let me just add one other story that comes to me right now. I had a Japanese friend who went to China to study at the University of Beijing. He had rented out this big apartment with two of his Chinese friends and it was really dirty, so they had to clean it up. Each of them had their own room and they were young guys, so they got really hungry. They just wanted to get the place cleaned up, then go out and get some beers and have dinner. My friend’s two Chinese friends, they had already cleaned their rooms, but my Japanese friend, he had taken his mattress off of the bed boards because underneath his bed, between the bed boards, it was really filthy. He couldn’t sleep, knowing that it was filthy under his mattress. One of his Chinese friends said, “Don’t worry about it. Nobody’s going to see it.”

When he told me this story, it hit me that, even with many ordinary Japanese people, there’s this concern, this awareness for what is not seen, this desire for cleanliness, for purity, but also this care for things that usually don’t get noticed.

The Japanese World of Sound and Silence

What new layers of exploration are emerging for you in your work?

In my exploration of Japanese culture, the past few years I’ve really made a deep departure into the Japanese world of sound and silence. Part of the inspiration for this is that, in recent years, I’ve just become so aware of how much I overuse my eyes, whether it’s taking photographs or whether it’s on the computer screen or my phone screen. I’m feeling how it disperses my energy.

What I find is, when I focus my eyes on something, this seems to really engage more of the analytical part of the brain, whereas if I let my field of vision just relax and go into a gaze and just to become aware of the perimeter of my vision, this is more of an intuitive realm and, in this realm, there’s this place where auditory awareness overlaps and there’s really a sweet spot there that is inspiring a new body of photographic work that I’m doing.

In my photographic work now, I’m exploring this realm at the edge of vision, where auditory awareness overlaps.

I’ve also started playing music, and I’m discovering how this beautiful world of sound is opening up inside of my brain and expanding my connection with the world, especially through echoes. I have found places in Japan where the echoes continue for 12 seconds, 15 seconds, even 18 seconds.

The beautiful thing about an echo is, when it disappears, just there at the end, we hear it, we don’t hear it, we hear it, we don’t hear it. Then, when it finally disappears, we’re left with this most exquisite silence.

I think a lot of it comes from finally beginning to really be comfortable with myself, with my imperfections, my imperfect relationship with the world, and just being able to relax into that, to relax into the pain of living. Then, by doing that, there are moments of joy, but always moments of new exploration, new realms emerging.

Everett Kennedy Brown is a multi-talented American artist based in Tokyo. He writes books in Japanese, performs ancient wind music and uses an 8×10 camera and hand-made glass negatives to explore Japan’s deep culture. His innovative images are in the permanent collections of museums in Japan, Europe and the United States. In 2013 he was awarded the Japanese Government’s Cultural Affairs Agency Commissioner’s Award in recognition for his creative activities.