A Temple Garden

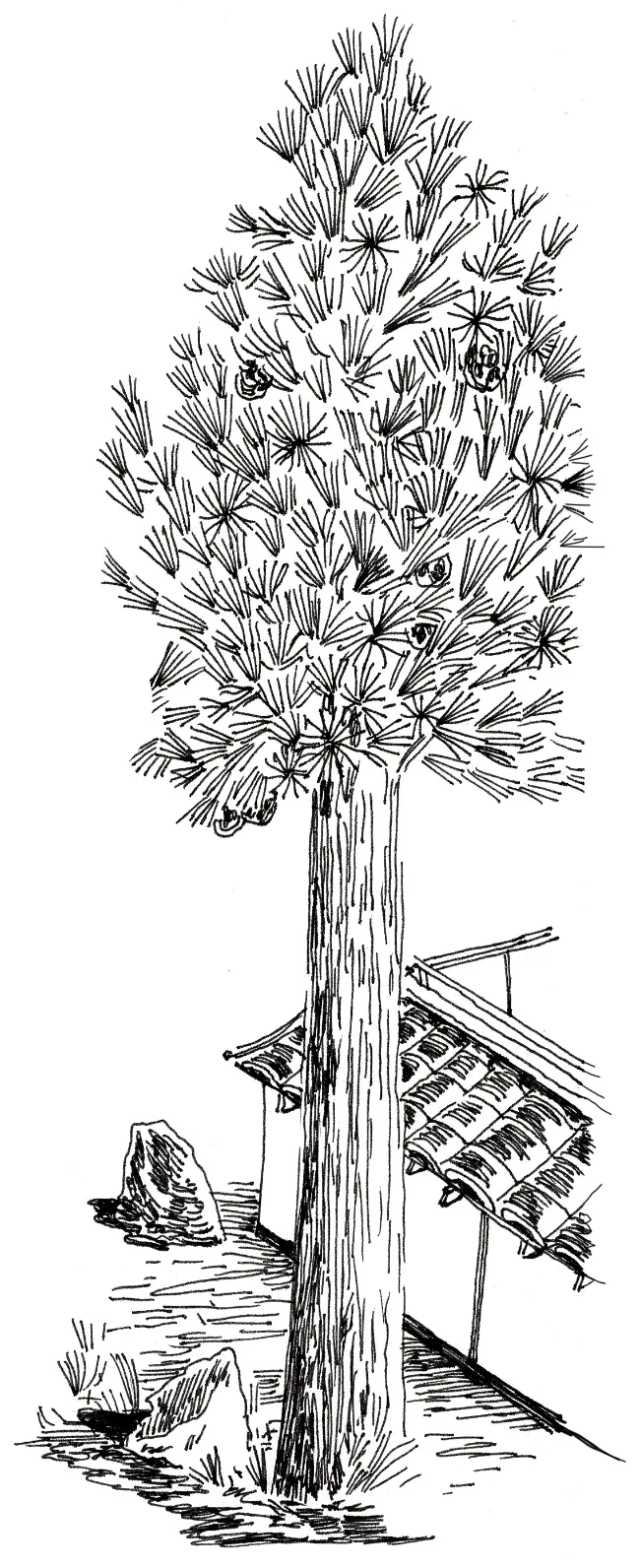

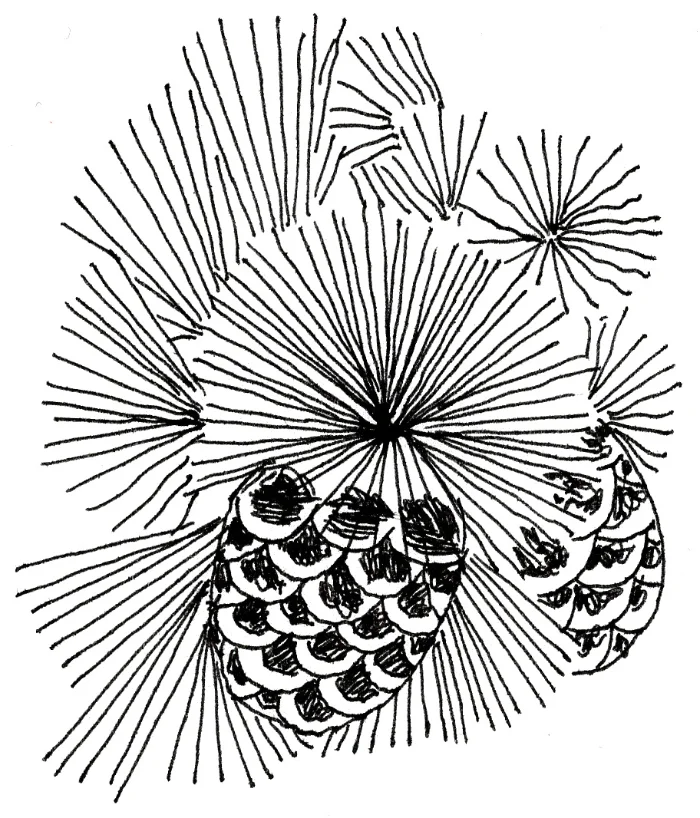

The pine trees here grow tall, in shapes that are almost like long tubes or what a gardener would call columnar. Of course, they do not grow that way naturally, they are shaped with scissors and saws, but it is unlike the way any other pine trees are shaped in the gardens of Japan. And that is because this is not a garden. It is a temple.

The tall and lanky form of the pine trees here is called ‘terasukashi’ or temple pruning. They have taken on that form over the years because traditionally the maintenance of the trees in this temple was not performed by gardeners who were trained in the art of pruning but by young acolytes who were training to become Zen priests. In the past, there were many such young men who came in the hopes of entering the priesthood, and so there were always lots of hands in these temples to help with the care of the grounds. No need to hire a gardener. The young acolytes were simply sent up the tree and told to cut the branches off as far out as they could reach, the result being a naturally columnar shape.

I enjoy coming here just to walk around the sprawling temple grounds and see the many parts and pieces that make it up. Alongside where the pine trees grow is the central core of the temple. It contains several large buildings that are laid out in a formal Chinese style along an axis. From the outside heading in there is first an outer gate, sanmon, then a Buddha hall, butsuden, a prayer hall, hattō, and finally the residence of the head priest, hōjō. Around that central axis are randomly laid out sub-temples, tatchū, which are all but hidden behind their tall clay walls and elegant entry gates.

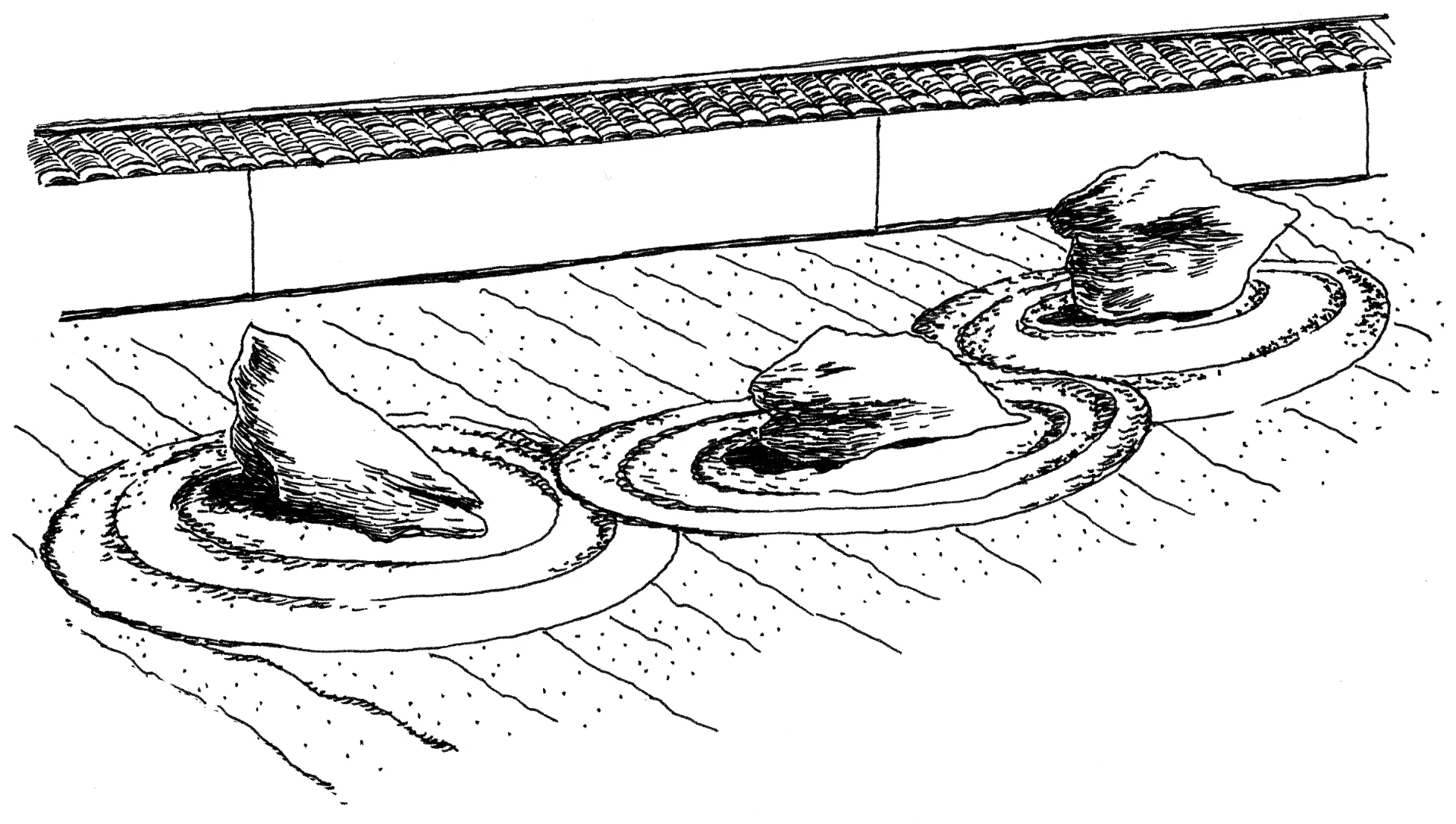

Between the subtemples are narrow roads that have been paved with stone. The work of paving was done over the centuries on an as-needed basis, so that it has both a sense of purpose and an organic randomness to its design. There are the beautiful interiors to the temples themselves, although few are open to visitors. And, of course, there are the enigmatic karesansui gardens that are found within the confines of walled temples, simple arrangements of stones and sand and moss that speak volumes more than their limited palettes would suggest possible. The pines and the architecture and the gardens—I enjoy all those aspects of the physical spaces of the Zen temples, but the most important aspect of Zen is not in the forms but in the practice, and one core of that practice is the concept of emptiness.

The True Meaning of Emptiness

Volumes have been written about emptiness. It sounds almost comical, that so much should be written about a concept called emptiness, and yet there it is. The descriptions of Emptiness present it as an ephemeral, ethereal concept that is impossible to express in mere words, even as oh-so-many words are written about it. But the idea that emptiness is an illusory concept that is difficult to conceive of is not the way I see it. For me, the concept of emptiness is in fact straightforward and easy to understand. It is not the meaning of emptiness but the practice of emptiness that is the real challenge.

A main tenet of Buddhist thought regarding the nature of reality is that all things are in constant flux and that all the things of the world—the people and the plants, the stones and the seas—come into being through a complex web of interactions and causations. At the same time, those same things are also being broken down by another complex web of interactions and causations. Arising into existence and being extinguished from that existence at the same time. Always. Always. Everchanging. This process is called “dependent arising” because no thing comes into existence in and of itself but instead is dependent on those endless webs of interconnections.

The difficulty in understanding the meaning of emptiness came about like this. If you want to explain the nature of reality, why things are the way they are, you could say that all existence is dependent on a web of interconnections. If you were to put things in reverse, and express what the nature of reality is not, you would say that there is no independent existence. However, instead of saying that the world has no independent existence, it was decided in the distant past to say that the world is empty of independent existence. That’s where the word “emptiness” comes in. The world is empty of independent existence.

A Web of Interconnections

It’s a terrible way to express things and the root of endless confusion. This is clear if you look at what’s happening with a different example. Let’s say that I have a bowl of soup and I tell you the soup is piping hot. That is an expression in the affirmative of what the soup is. Piping hot. If instead I express it in the negative, and tell you what the soup is not, I would say the soup is not cold. This is true, but it is not so effective a means of describing things because when you say the soup is not cold, it could be piping hot but it could also be just plain old hot or lukewarm or room temperature or even cool. So, saying that the soup is not cold is not as clear as saying it is piping hot. But if I go one step further and, instead of saying the soup is “not cold,” I simply say the soup is “not,” well of course you have no idea what I mean. If I say the soup is “empty of coldness,” there is some meaning to that description though not as good as saying piping hot, but if I say the soup is “empty,” of course you have no idea what I am talking about.

As already mentioned, the nature of reality is that all existence is dependent on a web of interconnections. That could be described, in reverse, in the negative, as being empty of independent existence. Taking that a step further, if I just say that the nature of reality is that things are empty, of course you have no idea what that is supposed to mean. How could you? However, when you realize that the word “emptiness” is just a symbol, a stand-in expression for a larger concept, which is that all existence is dependent on a web of interconnections, then everything starts to make sense. If every time you come across the word “emptiness” in a Buddhist text, you substitute in your mind the phrase “all existence is dependent on a web of interconnections,” everything becomes clear.

Form is Emptiness & Emptiness is Form

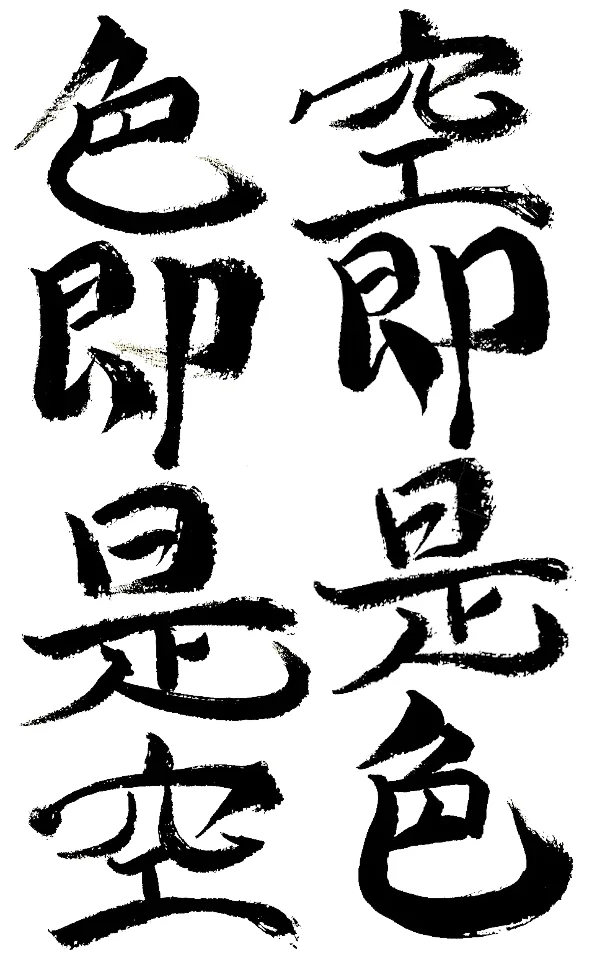

Take for instance a core line of the Heart Sutra:

shiki soku ze ku, ku soku ze shiki

Form is Emptiness and Emptiness is Form.

The word “form” refers to all of the things of the world—the aforementioned people, plants, stones, and seas. If you make the substitution I suggested, then that phrase from the Heart Sutra reads, “form is dependent on a web of interconnections, and the web of interconnections causes all forms.”

This idea of seeing the world, not as being made up of independent objects but as a system of holistically interconnected, mutually dependent entities, is so important because from that particular point of view flow all manner of enlightened understandings. To begin with it jibes perfectly with a contemporary scientific understanding of the world, whether you are looking from an ecological standpoint at the massively complex relationships between organisms and their environments, or looking at the carbon cycle that traces the flow of carbon through the air, earth, water, and life forms, or looking at the kind of fundamental interconnectivity that is expressed by quantum entanglement. I don’t think there is any scientific field that doesn’t agree that the world is massively interconnected.

A Truly Contemporary Mindset

Although many of the world’s religions find themselves at odds with scientific thought because it challenges some of their basic tenets such as the way they describe the creation of the planet Earth and the development of life on it, the concept of emptiness is totally in sync with scientific thought and, in that way, is a truly contemporary mindset.

Also from the concept of emptiness naturally flows ideas of environmental awareness and social justice, because the selfishness that lies at the root of environmental degradation and social injustice is not supported by a mindset that is based on the inherent interconnectivity of all things.

The hard part, as I mentioned at the outset, lies not in understanding what emptiness is—that is pretty straightforward, I think you would agree—but in attempting to embody that mindset in our daily lives. To foster what might be called an empty heart or an empty mind. To truly see the world as it exists with its infinitely layered connections.

Seeing with an Empty Mind

A temple cat appears from under the veranda. It leaps up, lands on the wooden floorboards, realizes I am there and freezes, all in one fluid motion. When the cat sees that I am no threat, it plunks itself down on the veranda, lifts a leg, and proceeds to lick its crotch in a display I can only imagine is intentionally meant for my viewing.

I try to see the cat with an empty mind, to truly see it not as simply a cat, but as the sum total of the array of interconnections it embodies. You are what you eat goes for cats too, I think, and as I can see by the little bowl in the corner of the engawa, this cat eats wet food, food that was brought by a truck from a distant factory where bits and pieces of leftover fish were processed along with god knows what into a semblance of a meaty meal, fish parts that came from a small coastal village where old wooden boats crowd the harbor at night and cast off into the unknown each morning before sunrise, including among them the fisherman who caught those very fish, who guides his boat across the cold northern waters crossing over shoals filled with kelp and clams and clots of shipwrecks out to deeper waters where the curved backs of whales trace graceful arcs through the moonlight and…

Wait. Stop! I’ve just begun to look at the cat, for cryin’ out loud, and have only begun to follow one stream of connections and already I’m lost down a rabbit hole. I haven’t even started to try to calculate the number of oxygen atoms in the air that the cat breathes in, or the number of CO2 molecules that it exhales, or the impact that the carbon will have on global warming, or the more immediate impact the nimble feline will have on the local songbird populations or … wait, wait, wait. There I go again, tumbling into the maelstrom. The human mind is not built for this. Can’t do it, it’s impossible. We cannot intellectually understand the web of interconnections related to a single temple cat let alone everything else we might cross paths with on a given day. That level of interconnection is simply too massive for anyone to grasp with their mind.

Knowing the World in Its True Form

I can’t understand it with my mind but perhaps I can understand it without my mind. The kind of perception I need is the kind that allows me to walk without calculating the individual firing of every neuron and contraction of every muscle cell that is required for my legs to move under me without falling flat on my face. A bodily understanding.

Being able to see the world with an empty mind is akin to looking at an infrared photo of a familiar scene and realizing that there is a whole new layer of information that you hadn’t been aware of. In the case of infrared, it is a flow of heat to and from the things that are there right in front of you yet unseen for lack of the right sensors. Having an empty mind or empty heart would mean being able to see the web of interconnections that underlies all existence as a real and tangible thing. To know the world in its true, essential form. To be enlightened.

Finding Yourself on the Cusp of Emptiness

I was asked once at a lecture where I had talked about this idea if I thought that I was an enlightened being. The question, of course, was tongue in cheek. I answered it in kind by paraphrasing Mark Twain. “Attaining enlightenment is easy,” I said, chuckling. “I’ve done it a thousand times.” Twain was talking about quitting cigarettes but the underlying joke is the same. Quitting cigarettes, as with attaining enlightenment, is only meaningful if it sticks, right? But let me ask, of the smokers among us, who doesn’t know what it feels like to quit cigarettes again and again? And of those among us who are seeking a true understanding of reality, who hasn’t found themselves on the inside edge of awakening more than once?

On an autumn evening, perhaps you are at a gathering of family and friends with all their individual histories and quirks and arcane relationships, and for a moment, for just a moment, you see it all, the love and loathing, care and neglect, all those streams that intertwine and electrify the room.

On a sunny Sunday, you are at work on your little farm, your veggie patch, and in turning the soil you cut an earthworm in two and realize, too late, that the very soil is alive, and alive in ways you can’t even imagine and that what you are eating when you eat those carrots and lettuces is in part the castoff casings of their lives mixed with rain and sunlight and air, and for a moment you sense that you and the worm and the sky and the earth and everything in between are simply extensions of one another.

On a blistering summer day, you dive into an ocean and as the cool water shocks you into alertness, out of nowhere you realize that someone else, at that same instant, has just dived into that same body of water half a world away, or not one but a hundred people, at the very same moment, and they, and you, and all the fish and whales and plankton in the vastness between you are there, in it all together. You sense this, that moment of true awareness, and perhaps for the thousandth time, you find yourself on the cusp of emptiness.

An exquisitely small insect flies over and hovers in front of me, close enough to reveal the fragile details of its little body. A perfect form that appears out of nowhere as if born of the air. I reach out as if to touch it and, in some way, know that I already have.

Marc Peter Keane

Kyoto, Japan

Marc Peter Keane is an American landscape architect, artist and writer living in Kyoto, Japan. He specializes in Japanese garden design, where he artfully blends Eastern and Western aesthetics and philosophies. He has designed and built numerous gardens for private residences, businesses and temples both in Japan and abroad.

He is the author of several non-fiction and fiction books including Japanese Garden Design, The Art of Setting Stones, Dear Cloud, and Of Arcs and Circles.

Text of Everything is Connected was originally published in Of Arcs and Circles by Marc Peter Keane, © 2022 Marc Peter Keane, used by permission of Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, California.