Naikan: The Japanese Art of Self-Reflection

Would you be willing to provide some background on Naikan and how it emerged from Pure Land Buddhism in the 1940s?

Sure. Naikan was developed by a Pure Land follower called Yoshimoto Ishin, who, along with his wife, ran a small family temple in Koriyama Prefecture, near Kyoto. He had engaged in a practice called Mishirabe, which was a secretive and austere form of self-reflection practiced for centuries but not officially recognized by Jodo Shinshu authorities.

Mishirabe involved going into complete solitude without eating, drinking, or sleeping for an extended period while intensely reflecting on one’s life. Yoshimoto attempted this four times. The first three times, he passed out before reaching any deep realization. However, on the fourth attempt, he experienced something profound—what his realization was I cannot know. Whatever the nature of his realization, it clearly had a lasting impact on him and his wife, who was also a devoted Shin Buddhist.

Yoshimoto realized that such an extreme practice was inaccessible to most people, and he sought to create a more structured and practical approach to self-reflection. In this way, he followed in the footsteps of Shinran, the founder of Jodo Shinshu, who centuries earlier had revolutionized Buddhism by making it accessible to common people—those who were uneducated or illiterate.

Similarly, Yoshimoto wanted to bring self-reflection to everyday people in a way that didn’t require complete isolation or extreme physical endurance. He made Naikan more accessible by allowing participants to sleep, eat, and sit in more comfortable surroundings. He also introduced a structured framework for reflection—three questions that form the foundation of Naikan practice:

- What have I received from others?

- What have I given to others?

- What troubles and difficulties have I caused others?

This revised and structured approach to self-examination was novel and made deep self-reflection possible for anyone.

One of the pivotal moments in Naikan’s evolution came when a senior official in Japan’s correctional system became interested in Naikan. He thought it could be beneficial for incarcerated individuals and contacted Yoshimoto about offering Naikan in prisons.

The official participated in his own Naikan retreat. That experience convinced him of Naikan’s power, and as a result, Naikan was introduced into Japan’s prison system. Research conducted in the 1960s showed striking results: prisoners who practiced Naikan for just one week had dramatically lower recidivism rates compared to those who did not.

I remember attending a conference in the 1990s where an ex-leader of the Yakuza—the Japanese mafia—shared his personal story. He had been involved in organized crime but was eventually arrested and sent to prison. During his time in prison, he participated in a one-week Naikan retreat.

After serving his sentence, instead of returning to crime, he became a gardener. Then, one day, two men in suits approached him while he was working. They were representatives from the Yakuza.

They told him, “The boss heard that you’re out of prison, and he wants you to come back.”

The man, with his hands covered in soil, politely declined. “I appreciate the offer, but that part of my life is over,” he said. “I’m just a gardener now.”

A few days later, the same men returned, saying, “The boss insists. You need to come back.” When the man refused again, they pulled out a gun, put it to his head, and said, “If you don’t return, we have orders to kill you.”

He simply put his hands together and prepared to die.

But after a long pause, they lowered the gun and walked away. They never returned.

Hearing that story, I was deeply moved. It showed me the profound transformation Naikan could bring about—even in someone who had lived a life filled with extreme violence.

Shifting Narratives

In my decades of teaching and practicing Naikan, I’ve seen countless people undergo remarkable transformations. Some experiences are as dramatic as the Yakuza leader’s, while others are quieter but no less significant—people telling me that Naikan saved their marriage, helped them overcome addiction, or changed their perspective on life. Many people were able to reconcile with aging parents towards whom they harbored long-standing resentment

That’s why I’ve continued to teach and practice Naikan for so many years. I don’t know of anything more powerful in softening our hearts and transforming our lives..

One thing I’m curious about—if you’re willing to share—is what your first Naikan retreat was like. How did that experience shift your outlook on life?

My first experience with Naikan was in 1988 at a place called Sen Kobo, a Buddhist temple that also functioned as a Naikan center.

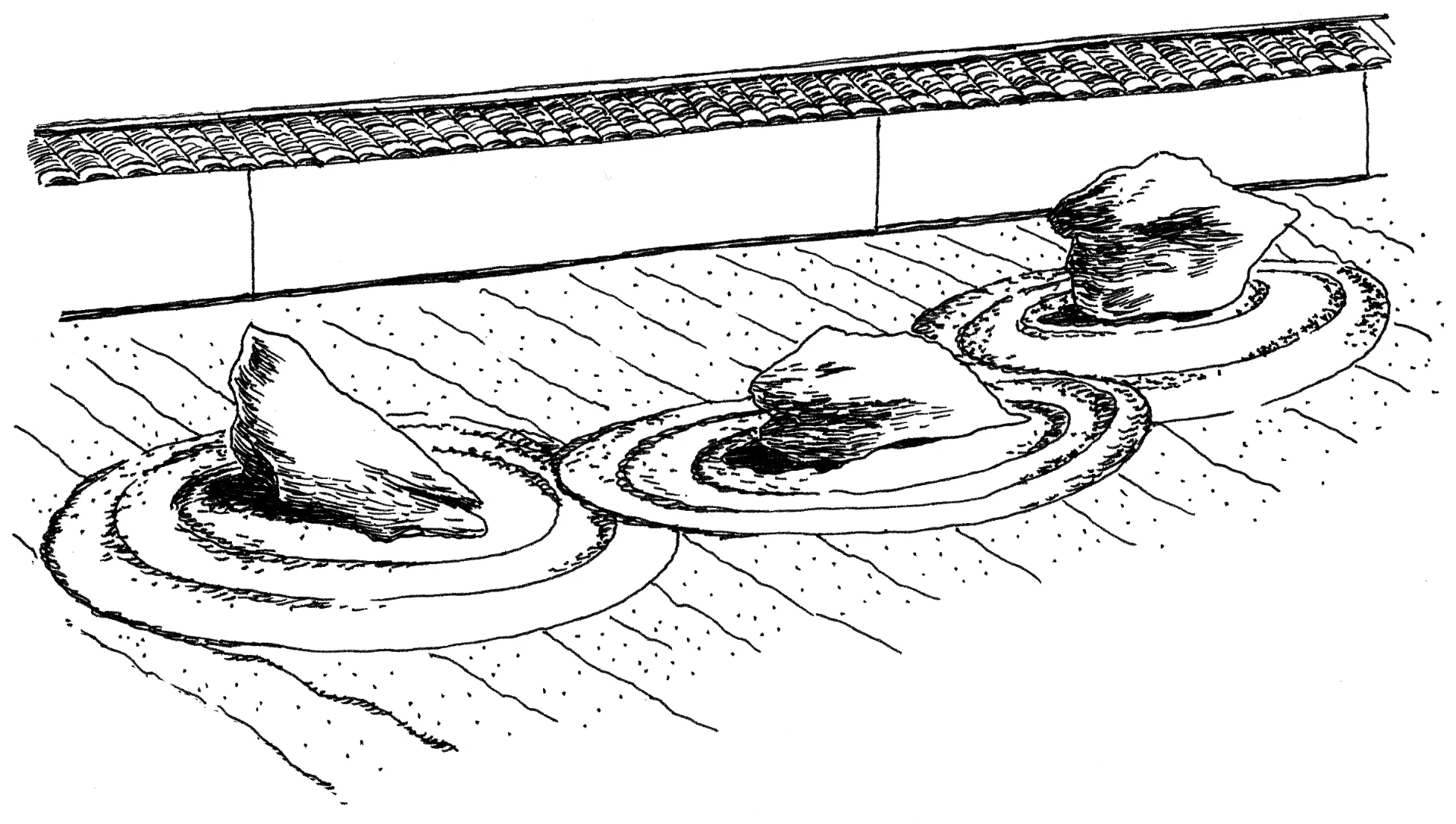

The setup was simple: a large hall, or dojo, with people sitting along the walls, separated by small screens. I sat facing the wall, flanked by screens on either side.

I spent about 15 to 16 hours per day, every day for two weeks, examining my life. I started with my earliest memories, which for most people begin around age five.

As is traditional, I began my reflections with my mother. I examined my relationship with her over set time periods—generally in 3-4 year blocks—and asked myself the three Naikan questions:

- What did I receive from my mother during this time?

- What did I give to her?

- What troubles or difficulties did I cause her?

I would sit with these questions for about 90 minutes to two hours at a time. There was no required posture—just cushions for sitting comfortably. After each session, a staff member would approach, bow, and say, “Please share what you’ve been reflecting on.” I could share as much or as little as I wanted.

After a day or two, my entire narrative about my mother, and then my father, began to shift.

Before Naikan, I viewed my mother through a negative lens. Our family had experienced violence, and I found her impossible to deal with. I couldn’t wait to leave home for college and escape the household dynamics.

But now, reflecting on my past, I saw things I had never acknowledged.

I remembered playing basketball and coming home late to find a plate of food left out for me. I recalled her taking me to swimming lessons, encouraging me to learn the piano, and convincing my father to buy a piano for our home. She arranged for me to have my first job. And she took me to the doctor periodically when I was ill.

Before, I thought of her as nagging me to practice music. After Naikan, I saw it differently—she was encouraging me. Today, my “night job” is that of a professional musician, and almost every time I perform, I think, “I wouldn’t be here if not for my mother.”

I was fortunate that she was still alive when I completed this retreat. The first thing I did upon leaving was write her a three-page letter, thanking her for everything she had done. There was a profound realization: I had never really thanked my mother for anything in my entire life. I was 33 years old at the time.

Everyone’s Journey is Their Own

That’s a profound shift.

It truly was. And I want to be clear—Naikan isn’t about pretending there weren’t difficulties in relationships. We did have family violence. There were times when the police and ambulances came. Those events were real.

But what Naikan showed me was that those difficult moments were only part of the story. My narrative had been selective—I was picking out pages from the book of my life that reinforced a single perspective of victimhood, ignoring the rest of the book’s contents.

Of course, I still got frustrated with her from time to time. But one major shift was that I stopped trying to “fix” my mother.

For years, I had believed that she was broken and unhappy and that I needed to fix her. That approach didn’t go well. During Naikan, a lightbulb went off:

I could stop trying to fix her—and that would allow me to just love her.

That realization extended beyond my mother to other relationships, including my subsequent marriage and my daughters. I have two adult daughters now, and like any parent, I want them to be happy. But their struggles are their karma, not mine.

In Buddhist terms, you cannot fix someone else’s karma. That doesn’t mean you don’t support and love them. But it does mean understanding that their journey is their own.

Naikan helped me to understand this.

Self-Power & Other-Power

Another thing that strikes me is how Naikan makes you more aware of the ways in which others—and perhaps even the world at large—are always supporting you.

I remember reading in your book about the concepts of Jiriki (Self-Power) and Tariki (Other-Power), which come from Pure Land Buddhism. These terms resonated deeply because we often focus so much on our own efforts in the world. We’re quick to notice when others block our progress, but we rarely acknowledge the countless ways in which they support us.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on how recognizing these two forces—self-power (jiriki) and other-power (tariki)—is part of the path.

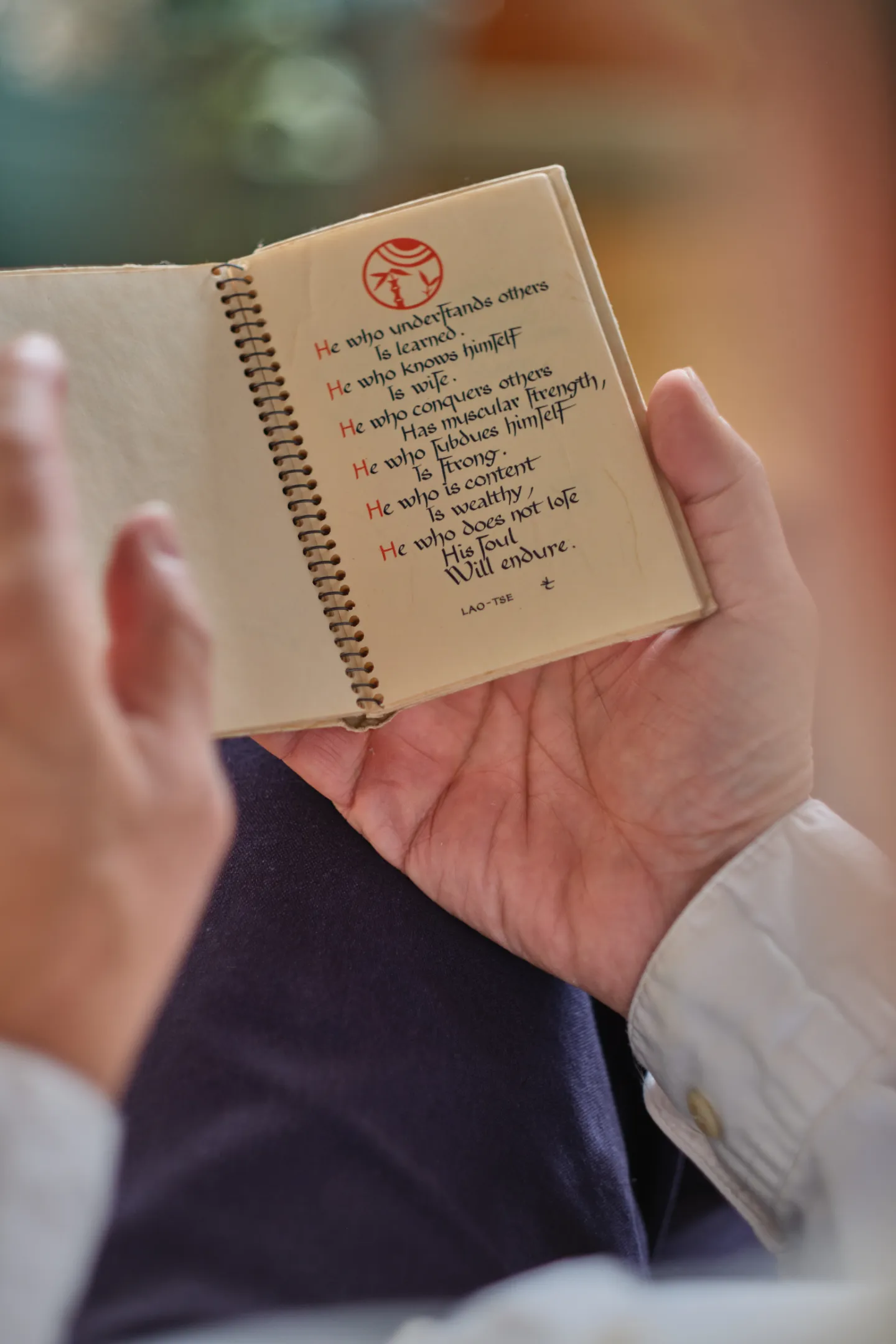

If we look at each of the three Naikan questions, these concepts naturally emerge.

Let’s start with the first question:

What have I received from others?

If I’m doing what we call daily Naikan, I can expand the scope. I can ask: What have I received from the world in the last 24 hours?

When I first started practicing Naikan, I was struck by the endless ways in which I was supported. I often ask people to list everything they’ve received in the last 24 hours. Number them. One, two, three, four. When you write it out, the sheer length of the list can be astonishing.

if I pause right now to reflect on the last few hours of my life, I see that I’ve received:

- Natural light from the sun

- Your attention and preparation as the interviewer

- Wi-Fi to facilitate our conversation

- Technology that makes this call possible between Vermont and the Netherlands

- My eyesight, which I especially appreciate after struggling with a serious eye condition

- A comfortable chair, with a contoured cushion supporting my back

- Oxygen, which I don’t even notice unless I consciously focus on my breath

And I could go on and on. This is tariki—Other Power. It’s the recognition that I cannot do anything without the support of others.

In the Heart Sutra, it’s said that nothing has any true form. When we look closely, we see that everything is made up of other things. This applies to us as well. I am not a singular entity—I’m made up of mitochondria, blood cells, bacteria and neurons. On a deeper level, I’m composed of atoms and subatomic particles.

So, what can I actually accomplish on my own?

Nothing.

I can speak only because someone taught me a language. I can teach Naikan only because the teachers before me—going all the way back to Yoshimoto and the practice of Mishirabe—laid the groundwork. I can play piano thanks to music teachers, the people who built the piano at my home and, of course, my mother.

Even creativity is not truly “mine.” If I write a poem, the words may be unique, but I did not create the language. And when creative inspiration strikes, I don’t control it. It flows through me, as though I am merely a vessel.

This, to me, is Tariki in real life—not just a conceptual idea, but a practical truth. Naikan opens our eyes to the countless ways we are supported and loved by the world, whether we notice it or not.

Seeing Ourselves Through the Eyes of Others

It reminds me of how much we focus on our own efforts and often overlook the generosity of the world around us.

Exactly. And this brings us to the second question:

What have I given to others?

This is where Jiriki—Self-Power—comes in. At first, we might think, Okay, here’s what I contributed. Maybe I cooked dinner, or maybe I helped jump-start my wife’s car when the battery died. Maybe I held the door for someone at the supermarket. These are things I “gave.”

But here’s where Naikan forces us to dig deeper. Once you make your list of things you’ve given, I encourage people to ask: “Which of these things didn’t benefit me in some way?”

And suddenly, the perspective shifts.

Take the dinner I made. I might have cooked for my wife, but I ate most of it myself.

Also, we may realize that the things we were able to give were because of the existence of other people, objects or forms of energy. For example, after washing the dishes. I could say, I washed the dishes, but I only did so because I had:

- A sponge

- Dish soap

- A sink with hot water

- Hands that function properly, thanks to my genes and doctors who helped me stay healthy

So even the things I “gave” were only possible because of countless forms of external support. I saw that my actual role was tiny. Even when we start with Jiriki (self-power), we inevitably end up back at Tariki (other power).

That’s a big shift in perspective. How about the third Naikan question?

Ah, yes. The hardest one:

What troubles or difficulties have I caused others?

This is where self-reflection becomes truly humbling. Most of us naturally ask a fourth question—one that doesn’t exist in Naikan:

“What troubles and difficulties have others caused me?”

That’s where we tend to focus. But when we flip that around we examine our impact on those around us. We ask, What is it like for my wife to be married to me?— that’s a very different perspective.

The third question allows me to see myself from her perspective. Naikan forces us to confront our own flaws, our self-centeredness, and the pain we’ve caused others. In Shin Buddhism, there’s a concept called bonno—which refers to all of our ego-driven desires, selfishness, anger, and judgments. Naikan reveals our bonno to us.

And some might wonder: Why would we want to look at this? Wouldn’t it just make us feel guilty or depressed? But Naikan isn’t about guilt—it’s about truth. I tell people before a retreat: “Your commitment to truth must be greater than your commitment to comfort or feeling good.”

If someone caused a car accident because they were drinking, and it left someone in a wheelchair for life— that’s a fact, that’s the truth. It may not feel good to look at, but truth matters more than how I feel. Once a recovering alcoholic who had completed a Naikan retreat said to me, “It’s painful to remember how I treated people when I was drinking. But what would be worse is to forget.”

In the West, many mental health approaches allow people to endlessly discuss how others have hurt them. Naikan, instead, asks: How have I impacted others? And that shift is profoundly life-changing, if we are courageous to see this.

From Separation to Interconnection

One of the key insights of this practice is how it shifts our perception from separation to interconnection. Many people live from a place of disconnection—from others, from the world, even from themselves. But Naikan seems to break down that illusion and reveal how deeply we are all interwoven.

When the world feels like it’s filled with resentment, selfishness, and division—not just at the national level, but even among friends, family, and communities—how do we find clarity?

For me, Naikan is a counterforce to judgment. Because when I engage in self-reflection, I come face-to-face with all the selfish, mean-spirited, and ego-driven actions I’ve done in my own life. And that makes it much harder to sit back and judge others.

There’s a maxim I often refer to: “Find compassion for others in your own transgressions.”

If I’m deeply aware of my own flaws, it becomes much harder to condemn someone else for theirs. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t oppose harmful actions—we should. But we can do it without hatred or self-righteousness.

In Buddhism, as you know, there’s the idea that everyone possesses Buddha-nature—even those who are causing tremendous suffering. So while it’s important to respond to harmful behavior, it’s also important to avoid dehumanizing the people responsible.

If we see suffering and injustice in the world, we have a responsibility to speak up. But we also have a responsibility not to let that turn into hatred. Martin Luther King Jr. embodied this beautifully. His philosophy was about fierce opposition to injustice—without hatred toward those committing it.

Growing up, my parents came from two different religious backgrounds. My father was Catholic, my mother was Jewish. And of course, I became a Buddhist. But I always think about Catholic confession. In Catholicism, when you go to confession, you receive absolution—you’re forgiven, and the slate is wiped clean.

Naikan doesn’t work that way. There is no absolution. The things we’ve done—our selfishness, our mistakes, our moments of being mean or losing our temper — they don’t disappear. They are part of our karma.

Think of your life as a book. Every day, you write a new karmic page. Whether you choose to read those pages or not, they still exist. And if we spend all our time focused on the mistakes of others while ignoring our own, we are in serious trouble – we remain ignorant of how we are living our life.

Starting Where We Are

That’s really powerful.

And I think it applies to the world right now. A lot of people feel powerless.

So what can we do?

We can start where we are. We can make our homes, our relationships, and our communities into small seeds of the kind of world we want to live in. I started the ToDo Institute in 1990, and for over 30 years, I’ve felt like the world has been moving in the wrong direction. But does that mean we stop trying?

No.

We try to steer the world in a healthy direction, even if only in small ways. And I think that’s what you’re doing with the Musubi Academy. Will Naikan change the world overnight? No.

Will the Musubi Academy? I hope so.

But even if it doesn’t, we do this work because it’s the right thing to do. And it starts with self-reflection. We can’t demand world peace if we’re estranged from our own families.

We can’t expect global unity if we harbor resentment toward our parents or siblings. We can’t expect others to show compassion if we are acting in response to our selfish impulses.

So we begin at home. We begin with our own relationships.

If you have hostility to someone in your life, start there. Reflect on your own role in the relationship. Ask: How have I contributed to this?

From there, we may gradually soften the hostility in our own lives—and that, in turn, softens the world..

I couldn’t agree more. Thank you so much for this conversation.