Coming Home

Tell us about how your interest in Japan and Japanese design and craft started.

It started from a early childhood, I was fascinated by the cultural aspect. I did martial arts, but was also into meditation.

When I lived at my parents’, I actually decorated my own furniture. I found this little boutique in Copenhagen run by a Japanese lady who had moved to Denmark with small Japanese teapots. I asked her if she could get me washi paper, and she got some from Japan so I could make my own shoji screens.

I was in my grandfather’s workshop who taught me carpentry, and I made shoji screens fitted to my parents’ 1950s villa, which was already Japanese-inspired with clean lines. I cut the legs off my furniture to make them low and made everything very minimal but warm. I practiced bonsai and all things Japanese.

This was before the internet, so I had to go to the library to get literature. I spent all my money on photocopying because I couldn’t get the books. My fascination came partly from books my grandparents gave me, and my grandmother worked at the Design Museum library. She once gave me a book on Japanese art that I still have – really beautiful with Hokusai prints.

My adulthood interest developed later. I always wanted to go to Japan but never got to until 2008 when Anne Marie [Buemann, co-founder of OEO Studio] and I went together. To me, it felt like coming home. I don’t think I slept much those 8 days – I really wanted to take it all in. Then we continued coming regularly, and a few years later we got our first Japanese client.

I actually don’t like to call them clients because they’re our friends. We just happen to work together – like with Masataka Hosoo and Shuji Nagakawa. They started as work relationships that became friendships, which is really how we see it. It’s the same with Ryutaro Yoshida, the founder of Time & Style.

The Geisha Will Let You Know

How was that first experience working with Hosoo, a historic textile craft family from Kyoto?

Japan has changed tremendously since 2008. Kyoto now is completely different – first of all, there were no tourists then. It was much more closed and conservative. When you visit House of Hosoo now with the flagship store and gallery, it looks like they’ve always been innovating, but at that time they were much more conservative, focused on kimonos. The furniture was low, not Westernized at all.

When we first worked with Hosoo, Masao-san, Masataka’s father, was still very involved in the daily business. This was when Masataka was just beginning to become the 12th generation leader.

Hosoo is a very old family and members of the oldest geisha house in Japan. We were there through the night to get to know each other, and Masao-san said at the end of the evening, “The geisha will let you know if we should do business together.” It’s so Japanese and traditional, like something from a movie. Luckily, she said yes.

Challenging Traditions Respectfully

At the time it was unprecedented for a Danish designer being invited to innovate one of Kyoto’s oldest craft businesses. How did that work when you had everything to prove?

First, we challenged the notion of Nishijin weaving itself. From our understanding, it means three-dimensional weaving with depth and layering. If we analyze that in an abstract way, could we work with the density of the textile to create transparency? That became curtains, which was an innovation. It might seem small, but for Nishijin that has existed for 1,200 years, it’s mind-blowing.

We created transparent textiles that challenged the craftsman, who was intrigued and ultimately solved the problem. That came just from asking the right questions and challenging traditions respectfully. Then we created a whole new product line for hotels, with the first order being 400 meters of curtains for the Four Seasons.

Thinking Outside the Box

Was that the same instinct behind the new chair you created with Time & Style for the latest Noma pop-up in Kyoto, where the seat is covered with tatami mat?

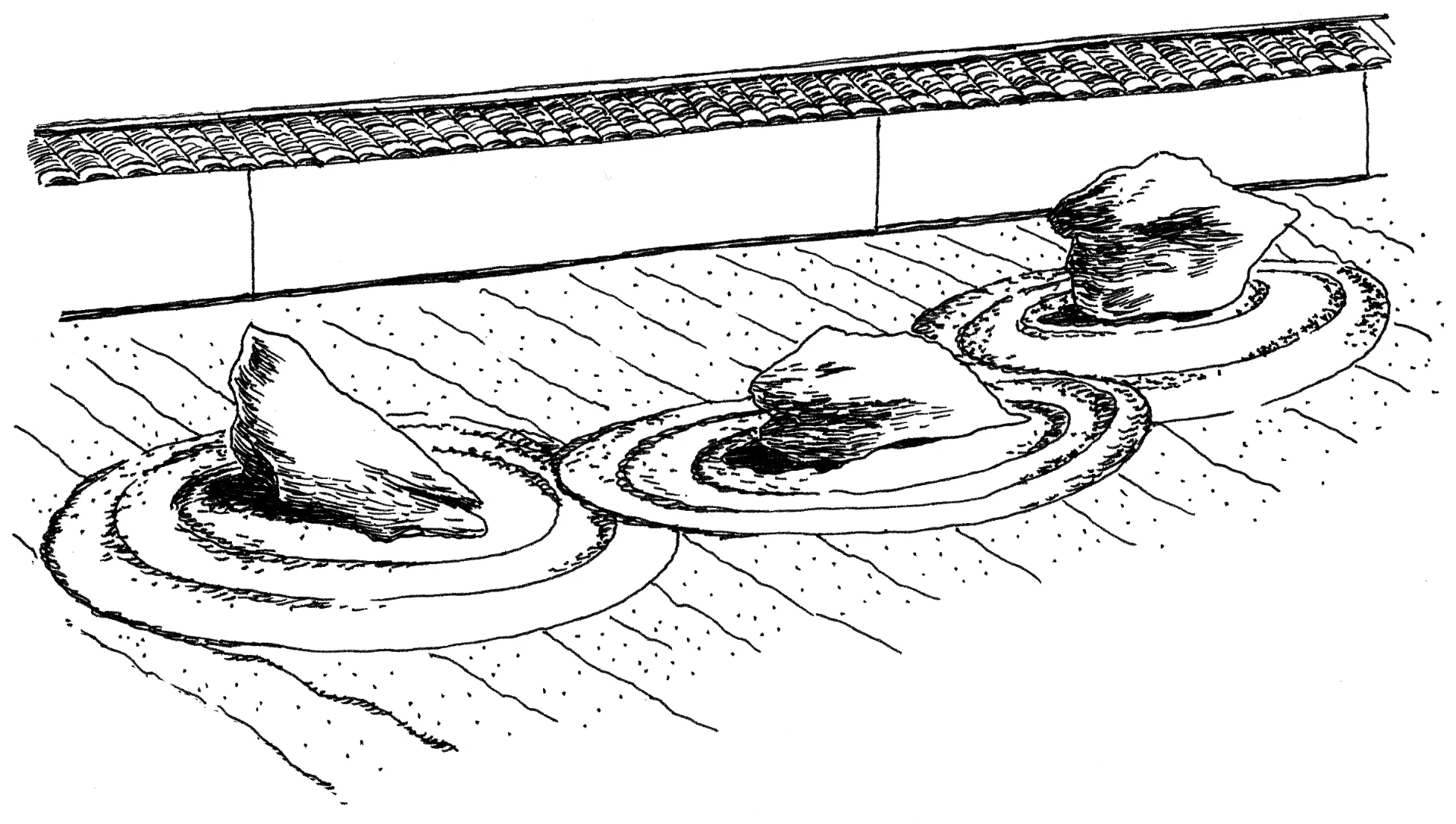

Yes, we had a beautiful conversation with Yoshida-san about this. He said because of being Japanese, there are certain ways of doing things – tatami is always flat and treated in a certain way. We wanted to use tatami three-dimensionally and make it curved.

I think that was an eye-opener for him and probably many Japanese. Mitsuru-san from Yokoyama Tatami said, “Nobody has ever done this with tatami before.” Coming from the Danish tradition of wood-bending, I thought, “If you can bend wood with steam, we must be able to bend grass and force it to shape.”

The result is a subtle innovation, but huge when you think about tatami and how it’s always been treated. It’s always flat, something you sit on or walk on – you would never create an organic shape because “you cannot do that.” But by thinking outside the box, we helped innovate something that has existed for centuries, creating a new product line and potentially saving a traditional craft.

A Sense of Purpose and Meaning

What wisdom do you feel is embodied in the craftspeople you collaborate with that we could all benefit from remembering?

I believe they all possess an innate respect and humility toward their legacy and their crafts. They carry their work with pride and honor while remaining grounded and approachable. The greatest wisdom they embody, in my view, is their profound respect for nature and the interconnectedness of all things. Key aspects to highlight include respect for others, reverence for nature, humility, pride in one’s path and craft, and the pursuit of one’s purpose in life.

Is there a Japanese concept or principle that you find particularly relevant or helpful to remember in today’s world?

There are many, but one that stands out to me is Ikigai, which translates to “reason for being.” This concept resonates deeply with me and with OEO Studio. We have always been driven by a sense of purpose and meaning. If something lacks purpose, we believe it is not worth investing our energy in. We are strong believers in this philosophy; it is part of our mantra and daily lives. Ikigai drives us, motivates us, fuels our passion, stimulates our curiosity, and gives us direction in life and in our endeavors.

Driven by Intuition

You refer often to tension but also perfect collaboration between intuition and logic in your work. How does that relate to your approach?

We’re very driven by intuition – taking the temperature, asking questions, being curious. It’s about tapping into the essence of what you’re creating. You need to know the essence to create a solution.

I think the difference between Danish and Japanese approaches is that we’re not afraid of challenging ideas, not in an offensive way, but out of curiosity: “How can we improve this?” Sometimes saying “no” is important so you don’t just follow what feels wrong.

We don’t mind being the small guys going against the big guys when we truly believe in something. It’s not about our egos; it’s because we believe it’s the right way forward. Sometimes you see something others don’t, and it’s really hard – like torture – when you do it because you don’t get immediate reward. People think you’re crazy, but you do it out of love and passion, and maybe ten years later, they realize it was amazing.

What is beauty for you?

When you frame it this way, it becomes a truly profound and complex question that is difficult to answer. Beauty encompasses many things, and it is also deeply individual and cultural. What is beautiful to one person may not be to another. I find beauty in contrasts, which can highlight one aspect over another.

Context plays a significant role—sometimes, even death can be beautiful. Ultimately, beauty is what you make of it; it is something deeper that evokes emotions. I find beauty in simple things, like a stone, and I believe that beauty can be found everywhere, even amidst ugliness. To me, life itself is beautiful.

Better than the Original

In your book you share one of many conversations with Rev. Takafumi Zenryu Kawakami, the head priest of the Shunkoin Temple established in the 16th century.

Did you gain any insights about Zen or Japanese culture from him?

There were actually many learnings. First of all, Shunkoin has the most insane, beautiful garden and the temple is beautiful. Everything is perfect. It’s like something taken out from a movie.

And Kawakami-san is so international, he knows everything about literature, poetry. He’s into all kinds of movements. And also, of course, he’s educated in neuroscience, and I find that combination of Zen and neuroscience intriguing.

One thing I found interesting was Kawakami-san’s perspective on what is Japanese. He said everything Japanese is imported at some point – sitting low, the painting techniques, the tea ceremony from China. But what’s fascinating about the Japanese is their pride in making something better than the original.

I have been reading a little bit about Zen Buddhism and it can sound really, really hard to become a Zen Buddhist or practicing Zen Buddhism. But when you have a conversation with him, he makes it sound more accessible – something you can practice in your daily life. We discussed how when I do woodwork, I forget about time and space – I’m just present. He said that’s a Zen state – being fully present with whatever you’re doing. That’s meditation too.

Creating Beauty & Fostering Connection

That makes sense. Real Zen is about practice, not theory. Whether you’re doing woodworking, painting, or formal meditation – being fully present is the essence of Zen.

Exactly. It’s when it becomes as natural as breathing – when the movement feels natural and you don’t think about it, you just do it.

What do you feel is the role and value of good design in today’s world?

I believe that design is as important as art, music, and literature. Design serves as a means of communication, education, enlightenment, and innovation, while also creating beauty and fostering connection.