Encountering the World of Buddhist Statues

Where did you grow up and what did you study?

I was born and raised in Kyoto’s Fushimi Ward, which is a very traditional place. It was an important port and trade town in the Edo period, with three big rivers that run through it. Those were used to bring in different materials to the old capital.

It’s there that I went to elementary school, junior high and high school. Then I studied for two years at a fashion design college in Kyoto. I also spent three years at another fashion design school in Tokyo. So in total, I studied fashion design for five years.

How did you first encounter the world of crafting Buddhist statues?

After studying fashion design in Tokyo, I decided to move back to Kyoto. At that time, I was actually enjoying drawing more than making clothes. I focused on abstract painting and other forms of art.

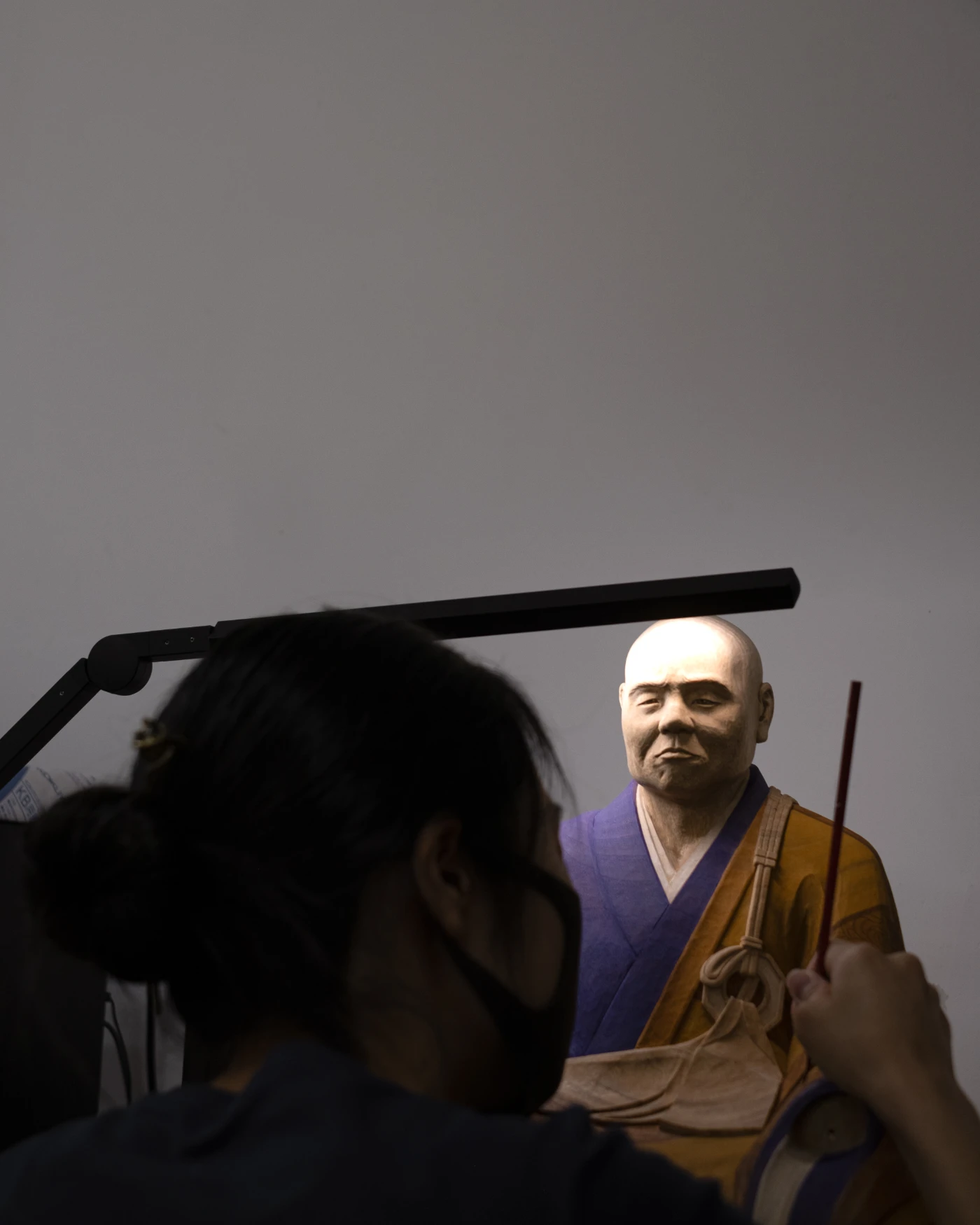

My to-be teachers were working on a large 3-meter-high, 11-faced Kannon statue, and they were looking for someone who could help with the painting of the statue’s clothes. I was introduced to the work by a friend, who knew my skills as a painter. That was my first time encountering the world of Buddhist statues.

Mesmerized by the Vast Scale of Time

What about that encounter made you decide to become a Buddhist sculptor?

Before my encounter, I had already spent five years learning to make clothes. Fashion is such a fast-paced art form. Every year there’s a new trend, and whatever I create for the year will go through tough competition, get selected or be replaced with the new trend.

When I started working with Buddhist statues, I realized that the statues I made would still be around for a hundred, five hundred or even a thousand years. To work with them I need to look into the world where I won’t exist any longer. The long-term thinking behind the creation and the vast scale of time one has to take into account simultaneously overwhelmed me, and mesmerized me.

The worlds of fashion and Buddhist sculptures seem like such opposites.

What was that transition like for you?

There are actually a lot of common factors. For example, I often say that clothing is a device for making the human body look beautiful. The human body is the main subject. So when making clothes, we study the human body; its bone and muscle structure. I also studied how cloth behaves, how it forms crepes, and the texture. I studied this for five years and thought I moved onto a completely different world.

However, it slowly became clear to me that Buddhist sculpture is the exaggerated form of the human body. So the study of bone and body structure is a prerequisite for sculpting Buddha statues. In addition to that, most Buddhist statues wear clothes. So having an understanding of the cloth’s movement and texture makes such a big difference in the variety of expression it enables the sculptor to draw upon.

I first thought these two worlds were completely different. But then I noticed that they were deeply linked. I’ve found my calling as a person who can express things in a way that only I can. This is exactly because of my life path and background in fashion. This made me even more passionate about the art.

Creating True Presence

What was your apprenticeship like?

I was 25 when I became a disciple. My masters were two brothers: the older brother practiced as a Buddha sculptor, and the younger brother made altars -wooden plaques. The workshop was small at the time, but it was growing, and they needed an apprentice.

For this kind of work, usually you start in your teens, so I could have been too late. They could have rejected me, but I was lucky enough to be accepted.

Traditionally, I would have had to go through a “steal the technique by watching” period, sharpening knives for several years, and spending 10 years before being allowed to touch Buddha statues. But they said they would teach me everything directly, which would be the shortest cut, as long as I made the effort to absorb and catch up with the teachings.

What feelings do you hope your work evokes in those who see them?

What I try to achieve most is a sense of reality. To create the realistic presence of a Buddha.

The most important thing is to let these divine Buddhas, with their beautiful shapes, manifest themselves in front of people, as if they can be reached with our hands.

That realistic presence is the key, and my expression through the drapery of clothing, and the construction of the human body helps achieve that. The sense of reality is what I think is my strength and something I feel I can offer to the people who see my works.

Reflecting on over 1000 years of Buddhist sculpture history, there were many, many sculptors. Each one of them polished their skills daily to create a Buddha statue that looked as real as possible. They all strived for true presence: how to make the shapeless divine stand in front of the worshippers as if it is really there. I’m one of them too.

Everything has Buddha Nature

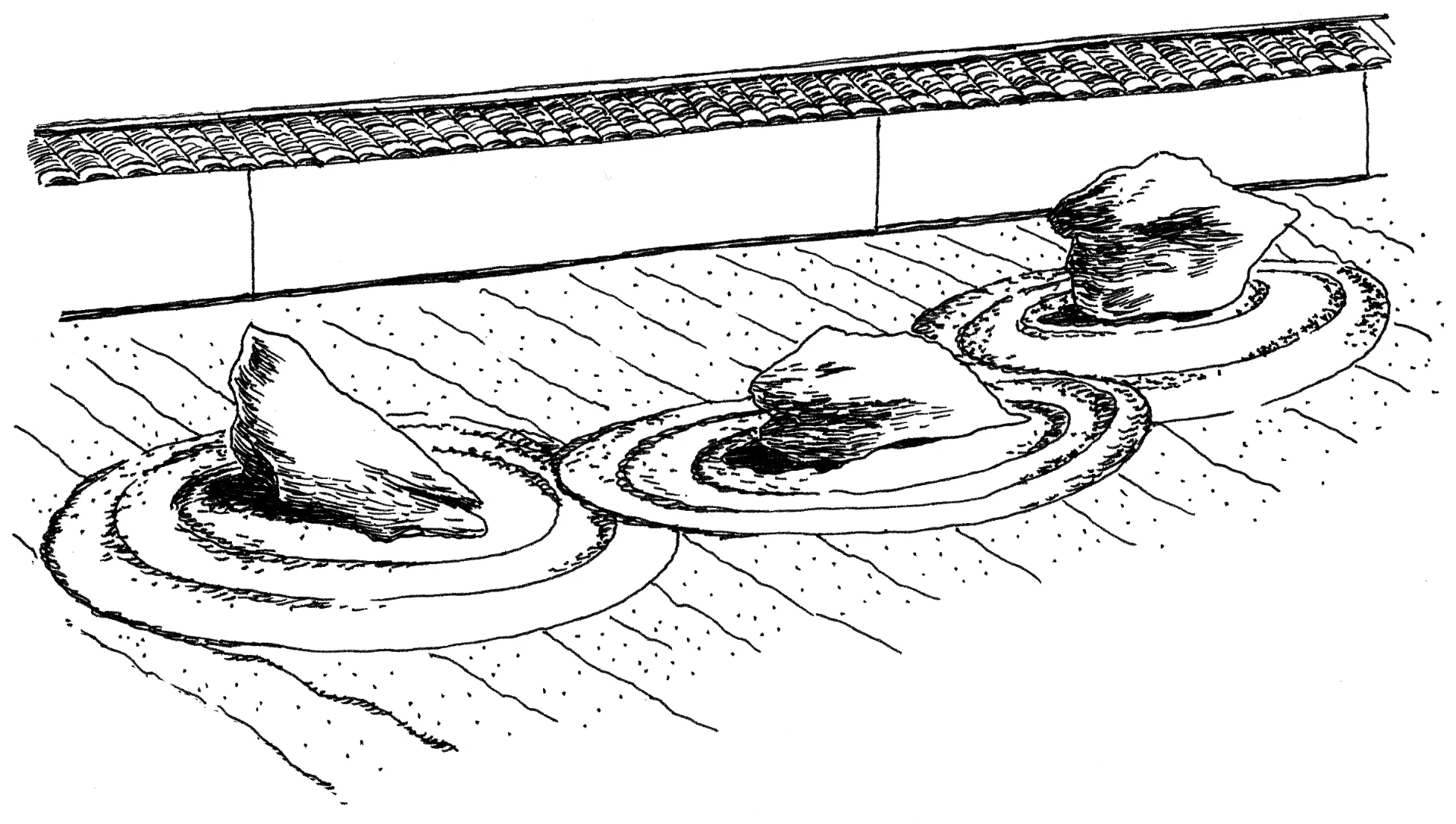

Originally, Buddha or divine statues did not take a realistic form. The oldest, indigenous religion of Japan is Shinto. In that teaching, deities are shapeless. They or their souls reside or manifest in rocks and other objects. This is called “Yorishiro Shinko” (依り代信仰), which can be translated as “receptacle worship”, meaning that objects are imbued with a divine soul.

Later, Buddhism came along and, in their beliefs, the Buddhas and other deities had forms. This was a completely opposite idea. Until then, Japanese people had always thought of deities as having no shape and had the desire to actually see them. So, the Buddhist idea of gods and Buddhas having tangible forms appealed to Japanese people then.

What makes Japan unique is that we haven’t lost those Shinto beliefs. Buddhism did not end up eliminating Shintoism, but rather, Kami -the Shinto deities- and Buddha, Shintoism and Buddhism, merged together and coexist to this day.

So Buddhism and Shinto have managed to coexist and mutually influence each other.

What is the common core between them that allows for this coexistence?

Buddhism believes that everything has Buddha nature. This is represented in the phrase “San sen sō moku shikkai busshō” (山川草木悉皆仏性), which means that even inanimate objects like mountains, rivers, stones, and trees, even some non-organic objects, all possess Buddha nature.

This is precisely what Shinto is about. These two teachings share the same core underlying philosophy, which made it possible for the two to merge and coexist, in my opinion. It’s easier to believe and sympathize with it when it’s expressed visually. That’s why Buddha statues are made.

Holding the Key to The Future

This core message of all facets of reality possessing Buddha nature, or being an expression of the divine, is important for us today.

It gives rise to a worldview that recognizes our interconnection and interdependence, as well as the inherent sacredness of all life. Something that is at the heart of Musubi Academy as well.

Very much so. We live in a mass-produced-and-consumed society. This goes for both materials and information and we’re deeply buried in it.

It is fine if we humans can adapt to it, but I already see some friction. People can only process and handle so much. We need to step back from this world of mass consumption and production and find ways to cherish what really matters to us. We don’t need so much to live and consume.

We need to find ways to live more simply. Some express it in the word “minimalism”, and this is what Shinto and Buddhism teach us. As the Buddhist phrase “I know to be content” teaches us, we can live abundantly without consuming so much. Shintoism and Buddhism offer many tips for living in that way.

We’re faced with many issues around food, overflood of information, and suicide. It is hard to stay sane when flooded with information, and the minimalistic approach of Buddhism and Shintoism will become ever more important in our current society.

I even believe that these teachings from Japan hold the key to the future of the world.

I believe so too.

A Dot That Will Become Part of the Line of History

You have worked in this field of Buddhist and Shinto sculptures for 18 years now.

How has your own view of life changed because of it?

It’s changed a lot. Before I started working in this field, I wasn’t interested in Buddha statues. I was only interested in Buddha paintings. Until I started working in this field, I had never thought about creating something that would last 1,000 or 2,000 years. I’ve never made anything on such a large scale of time, so that changed my perspective of making things drastically.

A Buddha statue has a history of something like 2-3,000 years. It is not something that I create from scratch in my lifetime. I am following the rules and traditions – the golden ratio constructed by my predecessors in order to attain the true magnificence of the Buddha statue.

At the same time, I also need to consider how to be accepted by contemporary society so the statue can be cherished and passed down to future generations, which will then become the tradition. So I also take the contemporary aesthetic into consideration. My work is but a dot that will become part of the line of history.

Before I started making these statues, I thought that if I made something beautiful, it would be good enough. I made things from my own selfish, self-centered point of view. But making Buddha statues is different. I have to think about all the people who have made them before me, as well as passing down the tradition to future generations. So I have a sense of responsibility on my shoulders.

Supreme Beauty Exudes from Within

What is beauty to you?

It’s a difficult question. I don’t know how many years left for me as a Buddhist sculptor, but my aspiration is to create a Supreme Buddha, a Buddha statue that possesses the ultimate beauty, at least once in my lifetime. But if you ask me what defines beauty in a Buddha statue, honestly I don’t have an answer to that.

To me, the ultimate beauty manifests in something that makes you put your hands together in prayer almost subconsciously. And you feel like you’re surrendering yourself to the statue.

Let me share an interesting episode that illustrates this…

I went to see an exhibition at the Buddhist sculpture school. There are lots of people learning to sculpt Buddha statues at the moment. There, I saw lots of high-quality work done by the lecturers and teachers.

But among the students’ works, which were not so great in terms of quality as sculptures, I found some that made me put my hands together, and brought tears to my eyes. When I encounter such works, I realize supreme beauty resides beyond surface, or technique. It’s something that exudes from within.

If I could articulate these qualities with my words, then I should be able to recreate it, too. So for now, if I’m asked what the ultimate beauty is, I can only say I don’t know. But I’d like to find out one day.

Precious in Its Own Right

You once said seeing your past works made you feel embarrassed and sometimes you want to destroy them. What are your feelings about this now?

I used to feel that way, as my eye for discernment is improving daily, so any past creations, even from yesterday, are below my standard today. So I work on improving my technique daily to catch up with my eye, and my eye surpasses my technique… I feel I’ll be in this cat-and-mouse chasing game for the rest of my life,

That being said, I really came to see a person’s life goes by in the blink of an eye. We may think 80 years is a long time, but compared to the Buddha statues, sculptures, and history of Japan, which have been around for thousands of years…? 80 years is just a tiny fraction of that time. And how many statues can one make in that fraction of the moment? Probably no more than 100.

So when I look back at my past works within that vast timeframe of history, I realize each one is precious in its own right. Even the ones I made when I was still learning are special. Technically, they need refinement and improvement, but the dedication that went into these works was incredible. I worked hard to make the best of it, and it was the best I could give at that time. I came to cherish that lately.

Either way, ultimately it’s not for me to judge. History will tell.

Purifying the Six Senses

Where do you find beauty in your everyday life?

As for finding beauty in daily life… Everything rotates around my work and I have a very rigid routine. I meditate every morning to gain clarity of mind. And decide which statue to work on for the day.

I reflect on my internal state through a process called Naikan (内観). Then if I discover I’m angry, I work on the statue of the angry Buddha Fudo san, the fire deity. When I’m calm, I carve a gentle Kannon Bodhisattva. I do this so there are no discrepancies between my emotion and the creation.

I also exercise and eat well. I eat almost the same thing everyday. I adjust everything to create the most suitable environment to carve Buddhas. Everything. Then what happens is that life gets simplified and sophisticated. For me, that is beauty in life.

Finally, I like climbing mountains. I’ve been to Mount Fuji and several other 3,000-meter peaks in Japan. I’d like to introduce the phrase “Rokkon Shōjō (六根清浄)”, which means purification of the six root senses. In Buddhism, those six senses are: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch and awareness. We repeat this phrase while climbing mountains so that the impurities that naturally accumulate within us will be cleansed by the power of the mountain.

In Japan, we climb mountains to purify ourselves, not to conquer them. I wouldn’t say Japan is the best or anything like that, but I’ve lived here for 43 years and so there are many things about it that I think are wonderful. And it makes me happy to be able to talk about it. So I am very delighted to be sharing my view with you in this way.

Having Faith

Do you have a final message for the Musubi Academy community?

I want to tell Musubi Academy readers about my dreams. One dream I have that I think is attainable is to create a Supreme Buddha. I want to create a great work that will last forever at least once in my lifetime. I’m working hard everyday to make this dream come true.

But there is another dream that may not be possible in reality. That is to create an object of faith for everyone regardless of the religion. Whether you’re Christian, Muslim, Hindu, or any other religion in this world, I want to carve a sacred statue that everyone in this world can worship and surrender themselves to.

Faith is very important, but it can also be dangerous. Many wars have been caused by faith. This is reality. But many people have also been saved by faith. There are many challenges in life, but having faith helps us cope with them. There are many different aspects of faith: it could work as a remedy but also as poison.

It doesn’t have to be Buddhism or Shintoism, but to believe and have faith in something other than yourself is crucial in leading a fulfilling life today. Our current society tends to focus on something tangible and realistic, but my message is to have faith to live a better life.