Shinto is Life

What is Shinto and what are some of its essential qualities?

Shinto is life.

It’s the path of human beings existing as a part of great nature. The path of each of us coming into our own, existing harmoniously within the rich, wondrous unfolding of great nature.

It is both an old framework for existing within nature, living within the flow of the natural seasons, as well as a very profound spiritual technology for removing the obstructions between us and the unfolding, pulsing universe. What we might call ‘life force’ or the animating principle of the universe.

Of course, everybody’s experience with Shinto is unique. We all dovetail with it in different ways. Each one of us is different and is a unique expression of great nature. So everyone’s connection with the live, pulsing, evolving cosmos is very personal and intimate.

How do you feel that Shinto has influenced Japanese culture and sensibility?

My opinion is that Shinto is the core essence of Japanese culture. Any place that you look at in Japanese culture, if you dig a little bit, you come to Shinto. Like the way of progressing through the seasons of life as I just mentioned. It’s so deeply woven into the very fabric of the Japanese soul and its different cultural and aesthetic expressions.

There’s the seasonal observances where we harmonize with the ever changing flow of nature through the seasons. Japan does that uniquely well. Like through the 72 microseasons, or all the different seasonal rituals, festivals and ceremonies still observed at the 80.000 Shinto shrines all across Japan. As well as in the few shrines established outside of Japan, like mine here in Florida.

Shinto is intimately connected with the real. With the real, live connection to nature as it constantly changes. Being deeply involved in the gorgeous adventure of just being alive. Shinto does a wonderful job of addressing such things, inviting us to fully inhabit this ever changing moment of aliveness.

During my early days in the 1980s, when I was allowed to look behind the scenes and really become an insider at a shrine in Japan, I remember being fascinated by the fact that everything was very seasonal and always on time.

There would be a seasonal ritual or festival and everyone was fully immersed in it. Then as soon as it was completed they moved into the next thing awaiting them. Everyone at the shrine was totally involved and focused on the current moment.

The Place of Power is the Current Moment

In Shinto you have this concept of ‘naka ima’ or ‘the middle of now’, right?

It sounds like that touches upon what you just referred to.

Could you elaborate on it for us?

Yes, ‘naka ima’ literally means ‘in the middle of now’. That’s such a profound concept, such a profound reality. Being in the present moment, fully alive. Seeing this moment as the pivotal place of vital power. The only moment that really exists.

We receive vibrations from the future world and vibrations from the past world. All those things exist simultaneously in the incredibly potent now, the incredibly potent current moment. The place of power is the current moment.

Only in the everchanging present do we experience our own aliveness and its source, what in Shinto is referred to as musubi; the forces of creation, connection and harmonization.

Whether we call it by this name or use a different word for it, we are all profoundly influenced by the forces of musubi. In the Shinto worldview, these forces are both horizontal and vertical.

We are inextricably linked with our family, friends, colleagues, neighbors and other beings. This is called yoko musubi, the horizontal connections. Then there is tate musubi. The vertical connections, which include both the stream across time from kami, to ancestors , to parents , to us and then to children and future generations. As well as the line that runs through us and this moment from the heaven to the center of the divine Earth.

The miraculous interface of all those forces is the ongoing moment of creation. It’s constantly changing and coming in and out of being. And that incredibly ephemeral instant, that is Naka ima.

And the most magical thing is that we exist and get to live there, at the ever changing interface of all those forces coming together in the moment as we experience it.

How cool is that!

Of course most of us, most of the time, are completely oblivious to just how miraculous and cool that simple fact actually is. Shinto is a path that invites us to wake up to that fact and fully inhabit this Long Now with our whole being. It’s a path of aliveness.

Being True to Our Essence

What initially drew you to Shinto?

As a child, I had the overwhelming feeling that everything that I observed in nature was true to its essence. A true expression of life. Nature was without artifice, whereas people often seemed with artifice. So as a kid, human existence seemed really, really odd to me.

I remember specifically walking to school in the Midwest and looking at tree leaves and blades of grass and thinking that about them. How utterly themselves they were. But I felt really strongly that human beings were awfully goofy. The whole situation of being human seemed really odd to me.

Even as a child, I was losing sleep over this. Of course, I was a really odd kid. I would be walking to school imagining that the atmosphere was very thick and viscous. And so I was kind of doing underwater Tai Chi movements and really thinking about the essence of water. What an odd kid, right? [laughs] Thankfully it all worked out.

So from a young age I was kind of searching for what was up with that. Why was the rest of existence so utterly itself and at peace with its place in the world, while so many humans I saw around me weren’t?

At the time I didn’t know exactly what I was looking for, but I was really searching for something. Being a child, I was optimistic and confident that I would find it.

I continued looking and became involved in athletic activities, but that was mainly a breathing meditation for me. Then as a teenager I became involved in Budo and Aikido training, because I was deeply interested in consciousness and ‘ki’ or vital energy. I became fascinated with being grounded and understanding one’s place in the world.

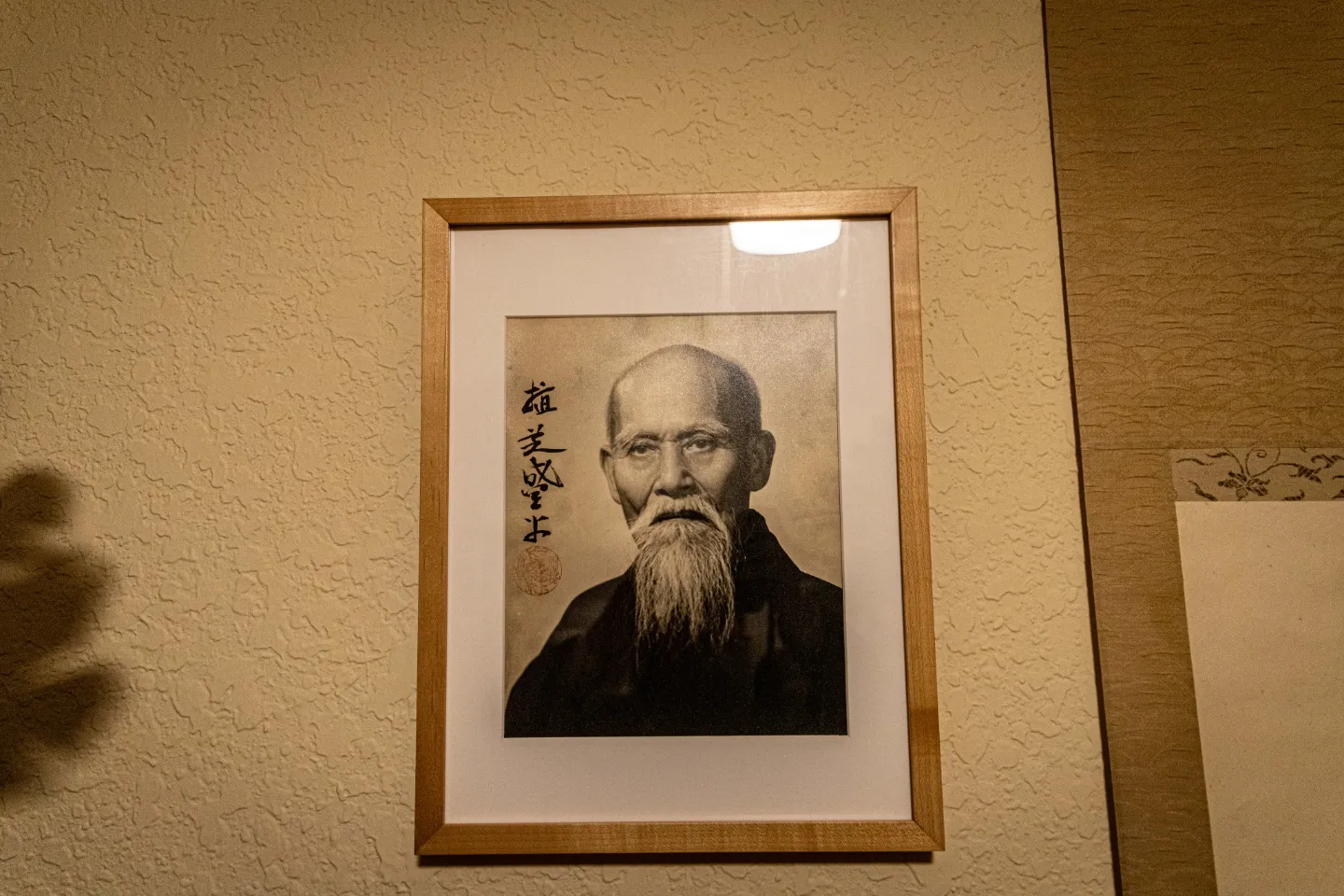

I became fascinated with the Aikido founder, Morihei Ueshiba, also called O’Sensei (Great Teacher). He was really a kind of Shinto mystic. I was drawn to his process and understood he was doing various types of embodied esoteric training every day to get in touch with this vital, live, pulsing cosmos. I wanted to know what he was doing that made him into this incredible being and martial artist.

Discovering Shinto’s Esoteric Practices

I was looking into Shinto as best I could, but it was in the 60s, long before the Internet. So getting information about something obscure like Shinto and its esoteric practices was very different. But I managed to visit Japan a few times and was eventually invited to the Tsubaki Okami Yashiro shrine in Mie Prefecture that O’Sensei had a lot of history with.

When I went there, I had the goal and mission to gain a deep understanding of some of the lesser known, esoteric forms of Shinto meditation, as practiced by Ueshiba O’Sensei.

In Japanese these embodied practices within Shinto are called Shugyo. Shugyo consists of various meditations, breathing technologies, movement and energy cultivation exercises, as well as physical and spiritual purification practices like Misogi Shuho; the practice of purification in moving water like a river, the ocean or under a waterfall.

All of those are wonderful and powerful gateways for the body-mind to become a better antenna and conduit for subtle energies, to experience the fullness of life directly. They are the techniques to develop what in Shinto and aikido we call a ‘listening-body’, a body-mind that is deeply attuned.

So I was very lucky to have those experiences at Tsubaki Okami Yashiro shrine and to be patiently mentored by very high level teachers. Of course I was considered really odd to be so passionate about obscure subjects like that, but I stumbled in at the perfect time and place. At that particular shrine there were various shinto priests, called Kannushi, who were willing to introduce me, this strange foreigner, to these profound spiritual technologies. Learning those was the center of my daily activities and life focus.

To be honest that process continues for me til this day. And now, however many decades later, the experience of the practices have deepened naturally , developed and grown real roots and wings —-it’s even more exciting and in my mid seventies I’m still very passionately involved in the same practices every single day.

Whenever I returned to the States from those early visits, I began to teach these practices and share them with my community of aikido and budo practitioners, as well as those in the general public who were interested to live life with a deeper attunement to nature and the life force that pervades all things.

Every Culture had Something Like Shinto

I have always been fascinated by how Shinto simultaneously seems so uniquely Japanese in its beautiful forms and rituals, but underneath it lie such universally relatable insights and experiences.

Whenever I enter a shinto shrine I feel a sense of wonder, as well as a sense of deep settling and coming home to myself in connection to something larger.

What is your perspective on that?

Shinto is interesting because it’s unique and not unique at the same time.

Every culture at one time had something like Shinto.

Shinto is a natural spirituality. Human beings in ancient times all across the world were very, very close to the workings of nature, and so spirituality that was pre religion was in many ways a more true expression of people’s relationship with this kind of divine, pulsing cosmos that we find ourselves inside of.

Every place at one time, before more conventional religion took over, had some kind of natural spirituality. Most of those forms of natural spirituality across the world sadly did not manage to continue to exist, because their meetings with the later dominant religion was not so amicable. Just think of how Native American or Aboriginal spirituality has been marginalized and suppressed. And in most countries in Europe its old forms of natural spirituality have entirely disappeared from the national consciousness as well as daily life.

So Shinto is quite unique in that way.

It’s also unique in how it has an unbroken history. Where in almost every corner of the world native and indigenous forms of spirituality were either suppressed, destroyed or severely marginalized by the introduction of formal religion and colonialism, this did not happen to the same extent to Shinto. It could largely continue to exist, evolve, and refine itself over several thousands of years up to the present day.

Getting Right with Life

If you look at some of the challenges we face as a society, how do you feel a Shinto way of life or worldview could be part of addressing some of those challenges?

Well, obviously, we’re collectively in a pretty funky place.

Human beings are pretty darn goofy.

I believe that all human beings have this calling to get right with life, to come into harmony with their life mission. After 40 years of deep personal exploration, intense daily practice and supporting others on their journey, I can say that if you dig deep enough, Shinto offers answers to all the innate questions and seeking of a human being.

It does this by offering a highly refined model for how to harmonize with seasonal change, manifest gratitude, and clarify elements of your relationship with this life.

As well as by offering profound spiritual practices and technologies that enable you to really change your consciousness. Practices that allow you to increase your perception of the world and your true place inside of it.

We are waki mitama, divided bits of the spirit of great nature itself. We are no less divine than anything else, no less divine than the leaves of a tree or kamisama. We are all created from the same essence. So there’s this calling going on between our humanity and our divinity.

When that calling gets frustrated by not being answered, which I think is true for most people, we individually and collectively find coping mechanisms. And many of those coping mechanisms are pretty darn unhealthy.

So that’s what I think is at the very heart of the difficulty.

Following Nature

Could you share more?

The nature of Shinto thinking is that everything is alive.

When we realize everything is alive, we naturally come to a way of moving through life by following nature. Only if we’re intimately connected with nature, can we follow nature.

Following nature, especially in the times we live in, means more than minimizing our negative impact on nature and the planet. I feel it’s too late to ‘co-exist harmoniously with nature’, we need a much more active and humble approach and attitude.

Following nature means receiving your cues from nature. Actively looking for your information on how to move forward from within nature itself. Allowing nature to show you its ways of moving forward and progressing.

That is what I think the true value of Shinto in today’s world is.

What is beauty for you?

Life. Everything is just so overwhelmingly, stunningly beautiful.

Beauty for me is the experience of being alive. What a gift!

Gochisosama – A Small Experiment

Do you have a small experiment that people could take on to experience a bit of the Shinto worldview in their everyday life?

I would invite people to take a moment before receiving their next meal and preparing to eat it. Really taking a moment to think about the ramifications of that activity.

Allowing yourself to become aware of the life of whatever you’re going to eat to sustain your own life. Becoming conscious of the nature of those things and where they came from.

And depending on what you are eating, how they’ve been raised or harvested, and then prepared by people. Try to bring your awareness to everything that went into it now being on your plate.

Then become aware of how you’re going to chew them up, so that the components of these things will become part of you, offering their energy to you. How did they get their energy?

So as an example, think of rice.

Think of the life essence and the nourishment it received. The way it received vitality from the earth, as well as divine sunshine power. And in the course of their lives they incorporated these elements.

Then through Kami sama’s or great nature’s magical chemistry, these various types of essence of source, were converted into something that could be used as food.

And then your body breaks these things down and receives those. As you chew very well, eventually all that sunshine that the food has received is carried by your body. It is broken down and carried by your body to your cells. So it’s that sunshine that is now powering your cells.

Think about how that simple act of eating ties you to the universe, to the world, and how you are receiving source. And ultimately how you are taking in the source of all sources, the sun.

So ultimately, that power of divine cosmic vitality known as sunshine has been converted into something else, namely the rice you are chewing. And now you’re going to convert it back into a simpler form that will power your cells.

Then you say, I am humbly receiving this sunshine through this act. I’m receiving this vital cosmic vitality and empowering my life so I can come into harmony with and hopefully realize my mission.

Then after eating, you say, gochisosama.

I am so grateful.