Maintaining Your Passion

T is Takuma Noda

A is Aiko Noda

Both of you come from craft families.

How did this influence you and what lessons did you learn from them?

Takuma: My father was an independent textile dyer and made beautifully colored and patterned ‘noren’, the textile curtains you often find hanging in front of the entrance to a shop or restaurant in Japan, as well as other dyed textile objects.

Like me, he was someone who worked at home and sold what he made directly. I feel I was influenced unconsciously by his choice of colors and molds from a young age.

My father was utterly devoted to his work, day in and day out. If there’s one thing he told me, it was: ‘be serious about your work’. He told me to find something that I could continue to feel passionate about for a long time. So I believe the fact that I am in a profession where I can make what I want is down to this teaching of his.

Aiko: My father was in the family business and made Kyo-Yuzen kimonos together with my uncle and grandfather. These are the Kyoto style kimonos that are hand painted and dyed with beautiful patterns and illustrations.

I remember going with my grandmother to deliver the finished products of the three of them. It was a bright and colorful atmosphere, with all sorts of people coming and going. I recall being moved by the exhibitions of the gorgeous kimonos that each craftsman made with their own hands.

Learning a New Way of Life

I feel my father was very proud of being a craftsman. However, as I was growing up, the kimono industry began to decline and one of the large kimono organizations collapsed. The craftsmen’s work could no longer go on as before, so they had to close down the family business of making kimonos.

Looking back now, I feel that the closure of the family business is not entirely a negative occurrence. It is also proof that it was able to survive for a long time, but that now there is a chance to transform.

Because of these childhood experiences, what I value the most about how me and Takuma are able to work now is to spend time with each of our clients. The work is created through such time.

Could you say more?

A: I place the utmost importance on dialogue with the client. For example, as we communicate with each other several times before making a fusuma sliding door, we get to know each other and our personalities. It gives me the feeling of being allowed to enter a little into the lives of the people who live there.

When you meet people, you learn that there are a hundred different ways of living and thinking. On each occasion, we have the pleasure of learning a new way of life and through that encounter a new work of art takes shape.

Building Connections

When did you establish Noda Print and how has the journey been that brought you to the present day?

T: In April of 2011 we moved here to Shiga. It was right after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, which was an event that caused us both as spouses to consider a lot of things. We wanted to combine our home and workshop, but it wasn’t like we could sell our product straightaway, and we didn’t have any close friends or acquaintances in the countryside.

So at the beginning we relied on our parents to introduce their friends to us for work, and slowly we built our connections through various means centered around Shiga prefecture. It really was a gradual process, being discovered or recommended by word of mouth, and slowly we began to get known by all sorts of people, including some editors of publications that ran features on us.

From that point, knowledge of us spread through architectural circles and our name spread beyond Shiga to Tokyo and further afield, and we started receiving requests from those places.

A: We began when we were first in Kyoto, and we wanted to produce ‘fusuma’, sliding doors, together. For us it was important to create fusuma that were ones people could live alongside. So when we heard this place was up for sale, we thought having a separate workshop is fine, but that it’d be more persuasive for people to see us living with the fusuma we made.

We also wanted to try a completely different lifestyle to that in Kyoto, and so we really quickly made the decision to move everything out here. In this home we can show people that we don’t just make fusuma, but also incorporate them into our daily lives living as a family with kids.

Making Something Only We Can Make

Takuma, you apprenticed and worked at the traditional Kyoto based karakami company Karacho for five years, before establishing Noda Print together with Aiko.

Do you see your work as karakami or as something else?

T: It’s both karakami and something that incorporates a whole lot of elements from other influences. It’s presumptuous for me to say that we have gone beyond karakami, but we do want to create something beautiful and it is done with traditional karakami techniques.

It’s also easy for us to say we do karakami, when introducing ourselves to new clients, as that helps them grasp the majority of what we do very quickly. However, I do believe that what we make doesn’t begin and end under that label alone. There is a desire to break through that shell, maintaining the beauty of karakami while also creating something new with our essence.

A: I knew nothing about karakami when I began with my husband. So you could say I had a lot of freedom when I first began to learn about it. That freedom was what allowed me to come to appreciate the beauty of the traditional techniques passed down over time in my own way. And so when we began to work together we decided to combine my sensibilities with my husband’s handed-down technique to make something different to what has been seen before.

So we’re not too concerned about what to call our craft – we just want to respect the original techniques that we employ, while using them to make something that only we can make.

Simplicity & Presence

What have you learned from working with karakami that informs your perspective on life itself?

T: In terms of the work itself, you could say karakami is a relatively simple craft. The tools are very simple, and it involves just transferring a pattern onto a piece of paper. It really is simple, and I would like to keep it that way if possible. I’ve come to think that having a lot of tools or implements won’t really change much. Perhaps I’m just not that materialistic (laughs), but having a lot of expensive tools doesn’t automatically lead to making something good. So I want to keep things simple, including in the flow of my life.

A: So in my case as a relative newcomer, it’s less about making paper than it is about tailoring everything to suit a space. So whenever I enter a space I observe how things are placed and how the light enters the space, and if the floor is tatami or flooring and so on. These things govern how you move around in your house.

And ever since I became involved in this world of paper, it has really turned around my perception of how it can influence your bodily sensations and movement.

For example, you can sense the presence of a person on the other side of a fusuma even though you cannot see them. It can create an enclosed space without completely shutting out everything else. I think it’s a wonderful thing that has sprung from the Japanese mind. From that I can appreciate the beauty of tatami, shoji, engawa, which all feel created along the same lines. All these things change how you live and how you move within your life.

Creating Something Together

You typically create work that is customized and attuned to the site and space it will be in. Could you share a bit about your design process, the steps you take and how you create a work that feels in harmony with the space?

A: Firstly, all of our work is one-off order made, so we tailor everything based on where the client would like to install the fusuma. This is the most important part of our work. So when talking to our clients we always ask why they wanted to change their home or shop, and during those talks we hear a lot about things like their struggles or why they’ve come to make a change in their life. So we want to be able to make a space that can encourage a positive change in their future life. So we really pay attention and strive to create something together with the client.

How do the two of you collaborate on a project?

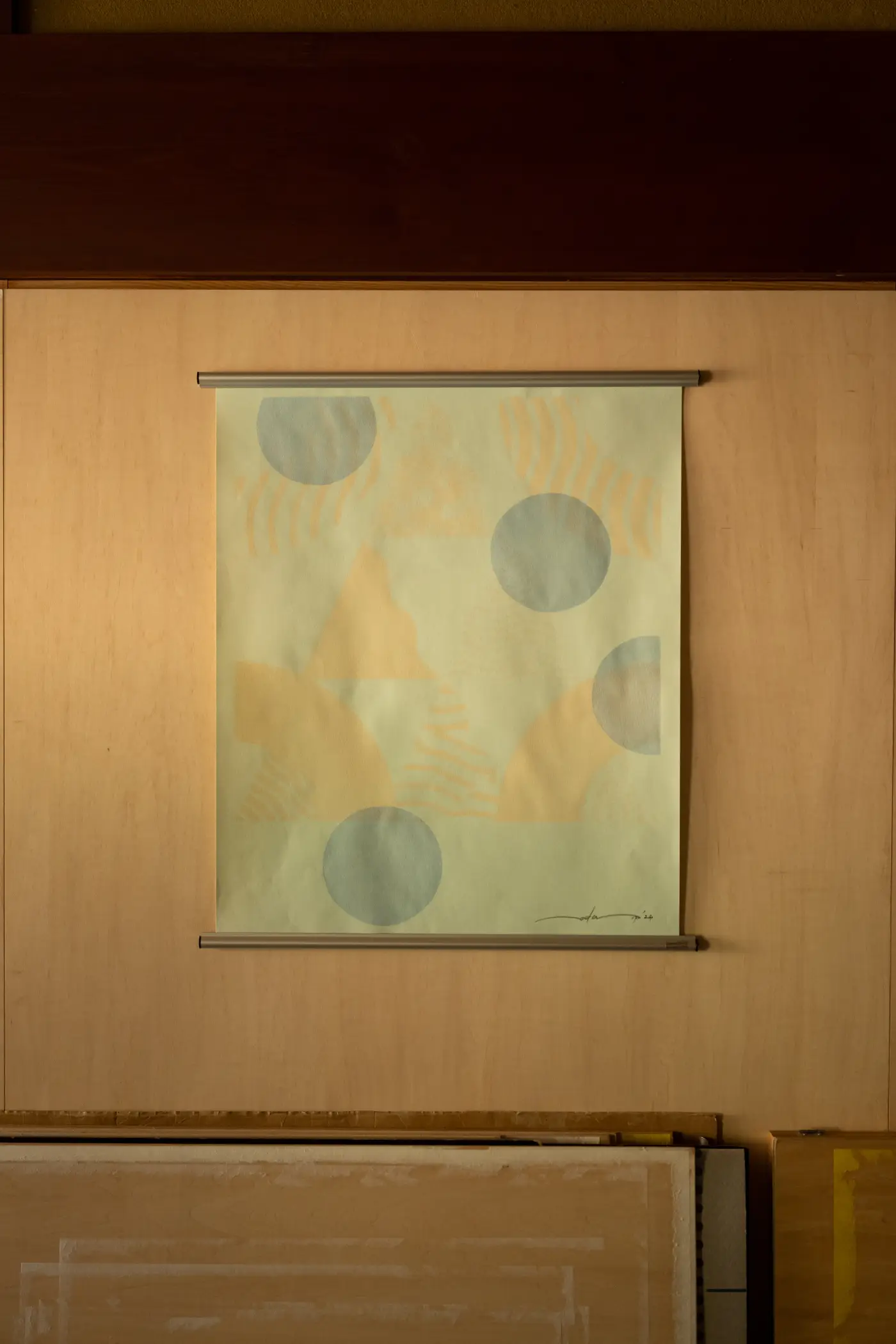

T: Aiko does the pattern design of the wooden printing blocks (hangi) we use and I use those hangi to make the actual paper works. When it comes to deciding the final design per job, sometimes my wife will come up with it by herself, or sometimes it will be me.

A: I’ve really discovered the appeal of working as a unit in the last few years. At first it was difficult working together and things did not progress very fast, but recently I’ve felt now that together we produce things that neither of us could achieve on our own.

For example, we all create based on our sensibilities. So when I create a design for him to print, he’ll find a way to use it that will be completely different to how I envisioned it in the first place. This kind of chemical reaction is always happening, and the end result is something that neither one of us decided independently to make, and is something no one has seen before.

Balancing Nature & Culture

In Japanese there is a thing called ‘A’un no Kokyu’ (阿吽の呼吸). When two people combine to become more than the sum of their parts, and it’s not something that is based in reason. It happens when we both try to exceed each other’s expectations. Having that constant feeling of surprise and freshness between us leads to interesting creations..

What are the sources of inspiration you draw on for your work?

T: We’re always in our home workshop everyday, and work is in very close contact with our everyday lives. Living with our kids, and being out in the mountains with nature, we can sense the transient beauty of the four seasons. Also, our village is very old, and we are blessed with lots of things from them.

I think I am influenced by things that I am in close contact with, whether they be colors or shapes or so on.

A: When I make a design, I take inspiration from almost everything in my life. To be more specific, as my husband mentioned earlier, our relationships with people around us influences us a lot, as well as the ever-present nature in this area, including the cries of animals. On the flipside the patterns of human to human behavior influence me too.

When a person sees a flower falling and says ‘how beautiful’, there is an unspoken sadness at the transience of life, which is something I want to express in a pattern. So I am always searching outside myself for things to inspire me.

I believe there’s a need to strike a balance between nature and culture for inspiration. For example when we went camping, we absorbed a great deal of nature, but afterwards I really needed to see something man made, like architecture or a painting.

Running Towards the Same Point

What is one of your most memorable projects to date? Why is it so memorable?

T: In all honesty, we put all our effort into every piece so it’s really hard to say which is the most memorable…

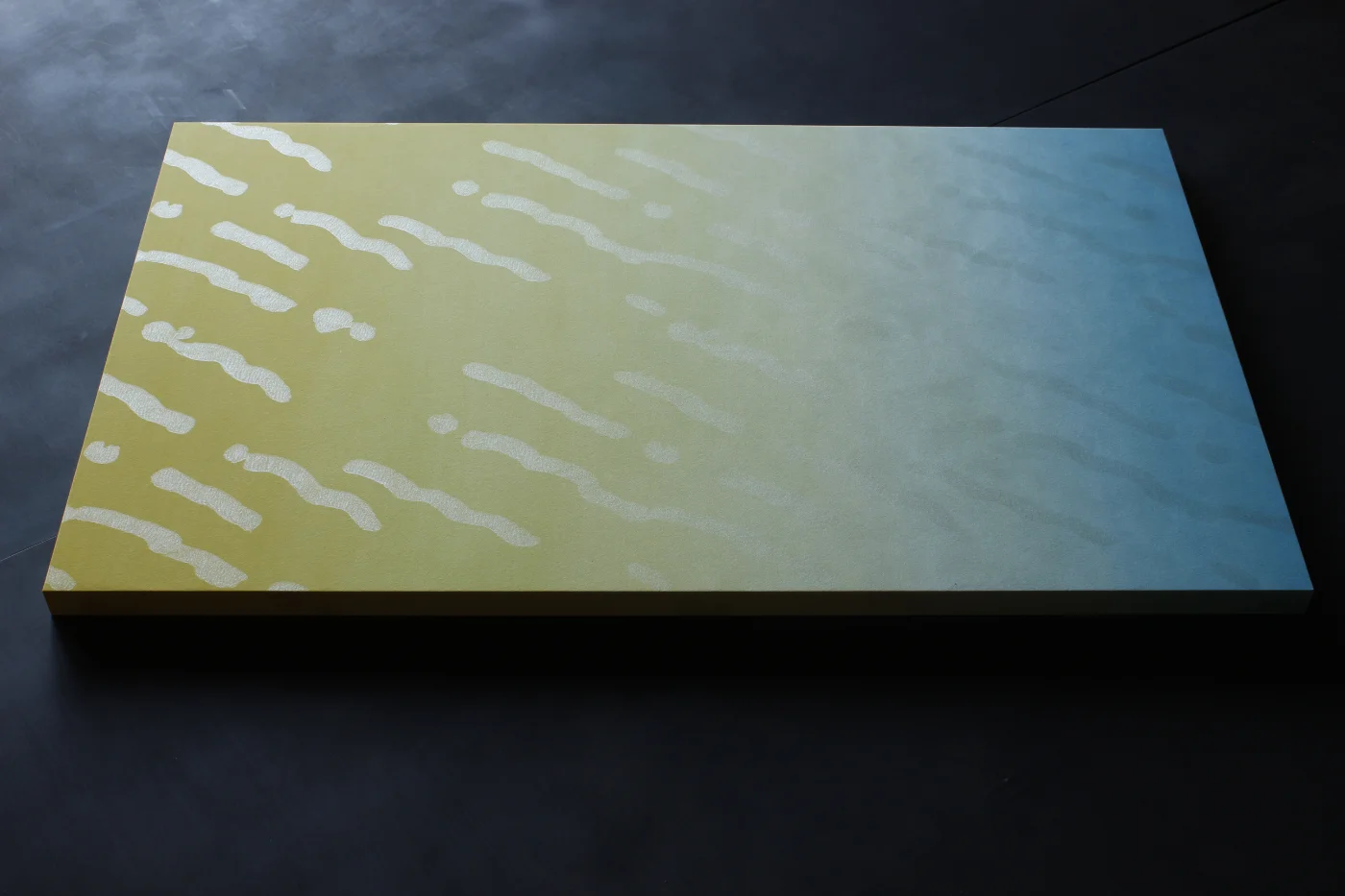

A: For me, it was the very very first fusuma we made. It reminds me of a time we cannot return to. We worked really hard on it with such pure feelings. It was the first pattern I’d made and I asked my husband to print it, and he originally said ‘this is too much’, because he was looking at it as someone who’d been trained as a traditional artisan. However I convinced him to try it – it was a yellow, blue and white print that now hangs in his family home. At that time his father was diagnosed with illness so we made it with the intention of encouraging him to fight.

Looking back on it now there are some areas that are very rough-looking but we can see our progress from that moment, including the evolution of how we work better together now. That very first fusuma was the point in which we both began to run towards the same point. We always remind each other not to forget how making that first fusuma felt.

Your atelier and home is located in a small town in Shiga, about one hour outside of Kyoto in the proximity of nature.

What made you decide to establish your atelier and raise your family here?

A: We moved here originally when we discovered his father was ill, but also we wanted a large atelier since we were going independent.

I came to look at this house by myself, and I reported on it and the scenery to my husband who wasn’t able to go, and he said ‘OK, let’s move.’ straight away.

T: I hadn’t even seen the inside of the house.

A: Just the outside. But I told him there was a road behind the house that looked straight out of a Ghibli film and a nice gelateria nearby, and he said ‘OK.’

The Importance of Craft in Today’s World

What do you enjoy or value most about it?

A: Every morning I take a walk to the nearby village (about an hour and a half) and I always enjoy running into our neighbors and the people of the nearby villages, as well as seeing the seasonal flowers, hearing the sound of running water, and it’s a great routine for starting the day’s work refreshed.

T: We live in a Japanese house, which changes a lot over the years, so we had to repair it a lot to make a life here, which has been very meaningful in terms of work and life. If we didn’t know anything we’d ask the neighbors. There are also fishermen in the village who’d just drop by with extra catch, and sometimes fresh vegetables would be left at our door by random, anonymous people. It felt like, more than when we were living in Kyoto, that people would reach out to us and care about how we were doing.

What do you feel is the importance or value of craft in today’s world?

T: In this digitalized world, with all these AI creations, I believe that the things that humans design and create have extra special significance and meaning. This digital world is convenient and extremely logical to use, if you consider it from a modern standpoint. But taking time and effort to make something has the result of being made with care and thought, and that is something I would like to preserve going forward.

A: In Japan there are a lot of amazing craftspeople who make amazing things, but their livelihoods are determined by larger forces they cannot control. For example, in Kyoto many kimono textile producers went out of business because it was supplanted by western style clothing.

So it’s really important to disseminate information about talented craftspeople, to draw attention to their work. As makers ourselves, we are very thankful for people who share this kind of information, especially since many craftspeople are not skilled at marketing themselves.

Things That Reverberate in Your Soul

What is beauty for you?

T: Well, it’s difficult to put into words, but things that reverberate in your heart or soul are beautiful. Whether it be music or art, if there’s something about it that makes you appreciate it, whether you can identify the reason or not, I think that touches on beauty.

A: It might seem corny, but accepting your present self for all it is is beauty to me. In life people face many adversities and emotions, ups and downs, and in those times you might doubt and worry, you might be helped by some people and help others in return…I think being able to forge ahead while connected to others is beautiful.

What do you cherish most in life?

A: In my case it’s my connections, not only with my family but with the wider community around us.

T: I also second that. People cannot thrive alone. We are able to get by because of the support and patronage of so many people, and for all of those connections we are extremely thankful.