Perfect Days

I recently watched the movie Perfect Days by German film director Wim Wenders. It is the story of a happy man named Hirayama who lives a quiet life in Tokyo working as a cleaner of public toilets. In several scenes of the movie, Hirayama rides his bicycle across an old bridge into Asakusa to eat dinner at his favorite little bar in the basement arcade of the subway station.

When I saw this movie, I could feel Wenders’ deep love and understanding of Japan. Hirayama regularly stops for lunch in a park and takes photographs of the dappled sunlight filtering through the leaves of trees with his pocket camera. This play of light that evokes a sense of tranquility and natural beauty is called “komorebi” (木漏れ日 ) and is commonly found in Japanese literature.

I was also surprised that Wenders paid homage to Asakusa – an old part of Tokyo that’s been a center of entertainment and cultural activity for centuries. Before the war, it was like New York’s Times Square or Montmartre in Paris- a place where many interesting and eccentric people gravitated.

Portraits of Kings

Asakusa also inspired many artists and literary giants. There were the novelists Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Yasunari Kawabata, winner of the Nobel Prize, who came to drink in the bars and write about the geisha and variety show performers, the hustlers and wannabes, the country clodhoppers and teenage prostitutes who came to Asakusa in search of a better life.

I had my first encounter with the soulful world of Asakusa back in 1988. I had just moved from Bangkok to start a new life as a photographer in Tokyo. One day, I was walking in the back streets of Ginza when I discovered the Nikon Salon gallery. There was a notice beside the door about an exhibition titled Portraits of Kings. It sounded interesting, so I stepped inside.

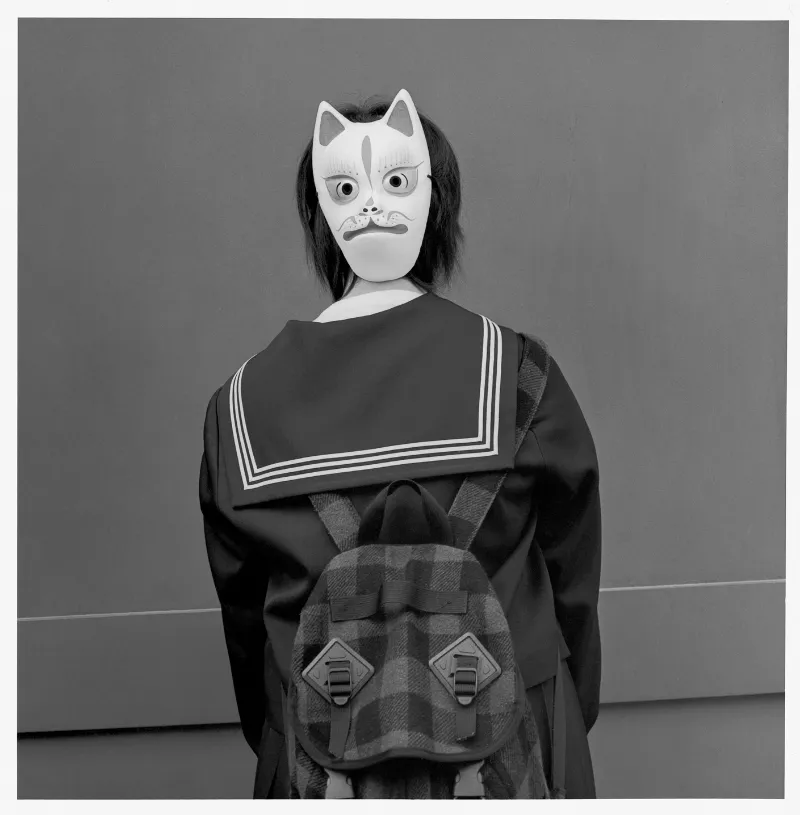

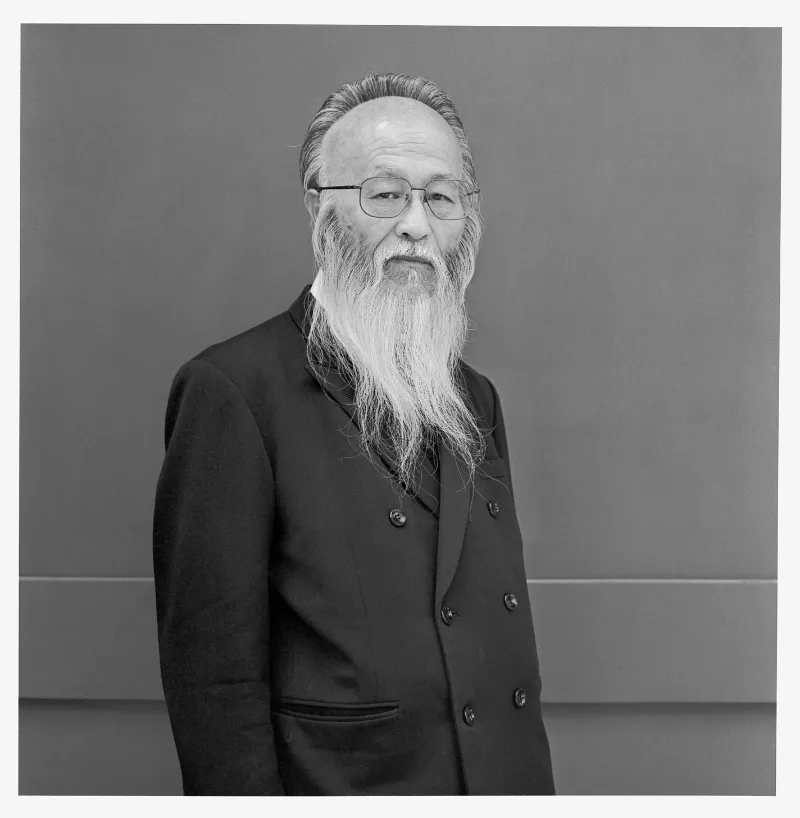

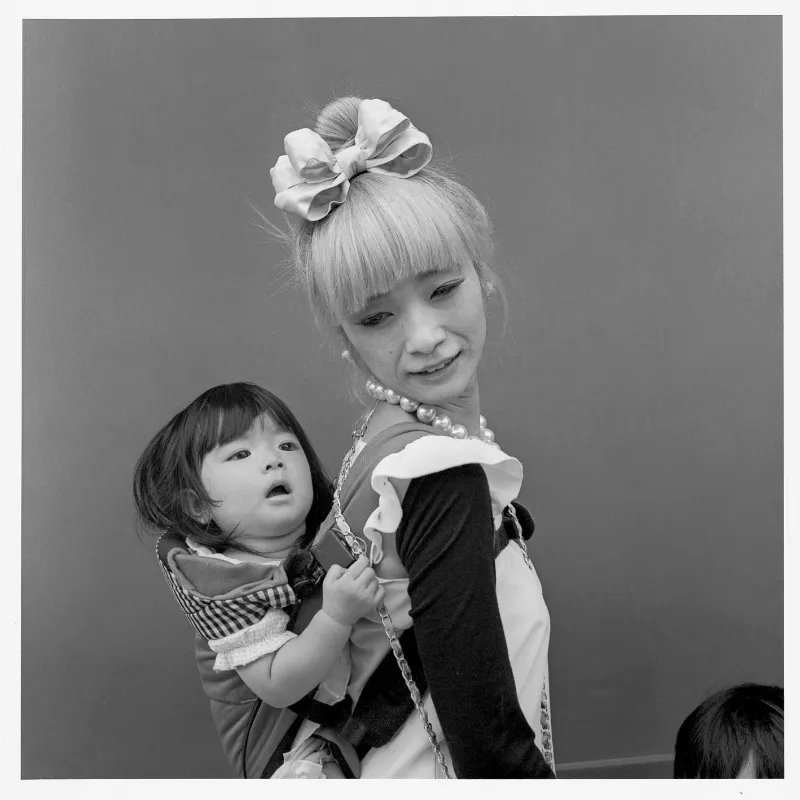

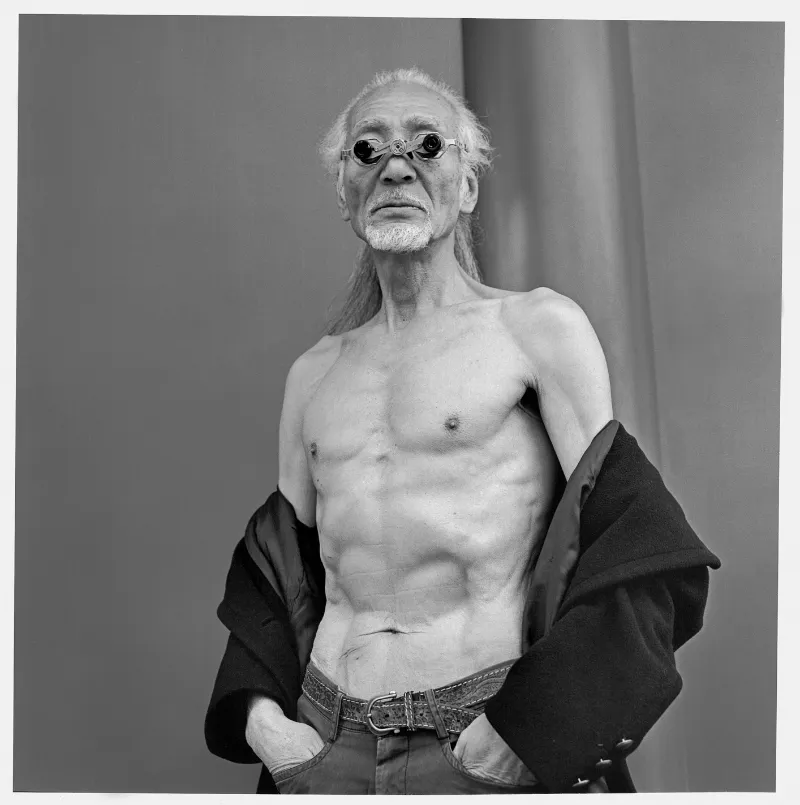

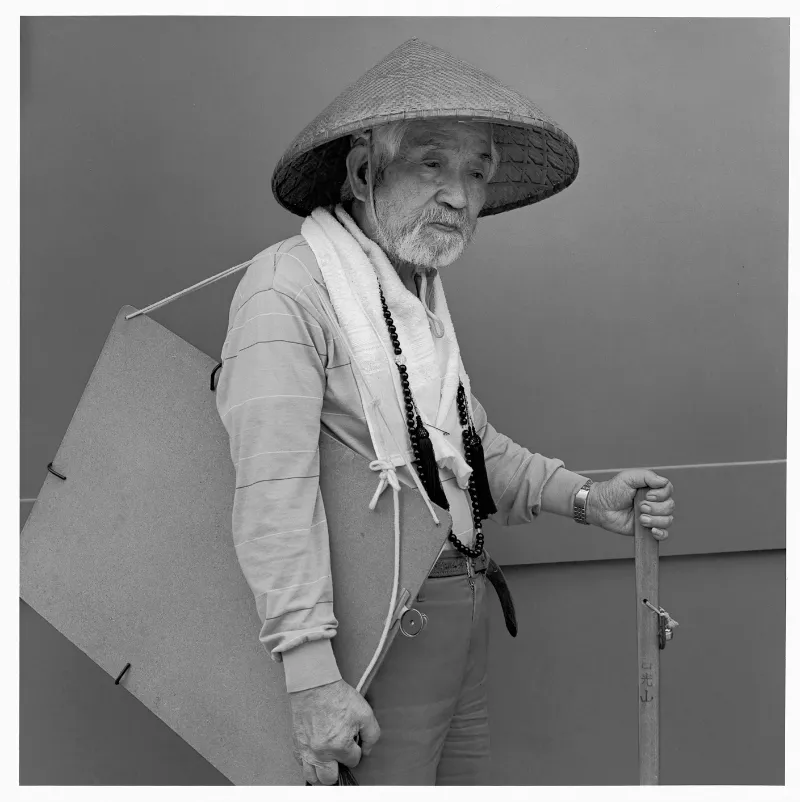

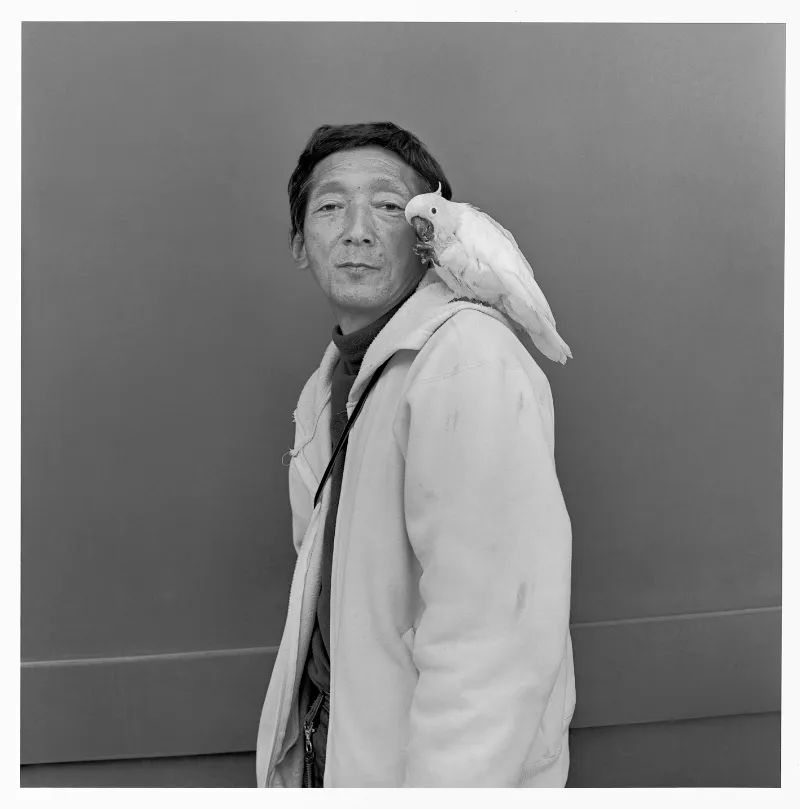

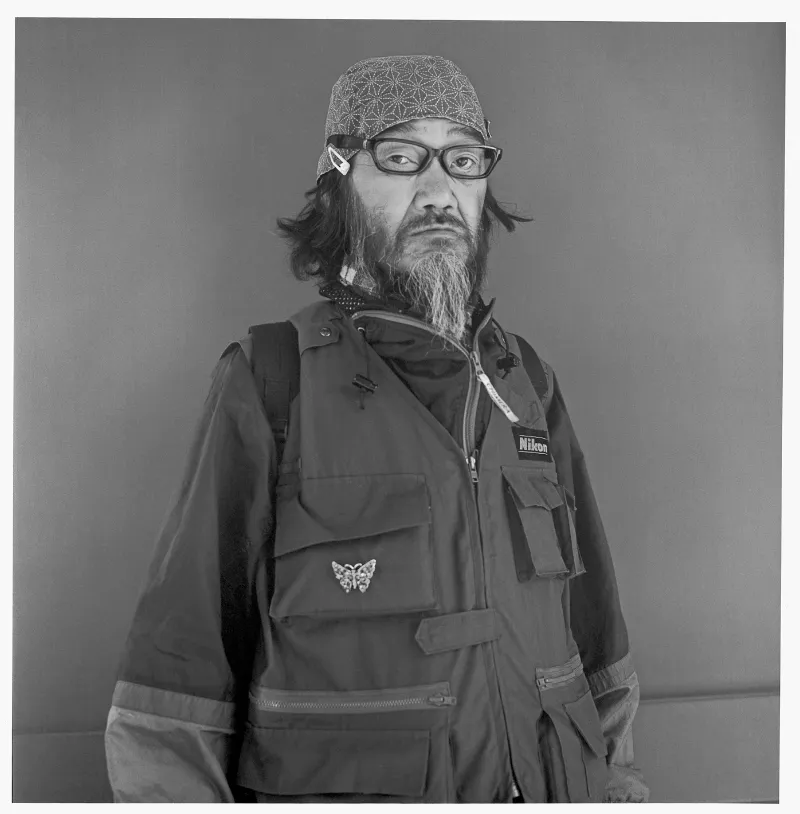

The introductory text on the gallery wall explained about the photographer, Hiroh Kikai, and how he had taken a series of portraits at Sensoji temple in Asakusa. I looked around at the large black-and-white photos on the walls and was startled by the menagerie of eccentric characters. There were portraits of humble people, done in a not vulgar way, and each image evoked the soulful presence of an individual who lived their own authentic life. Portraits of Kings was an excellent title for the exhibition, I thought.

A Philosopher Who Used his Camera to Make Sense of the World

In the center of the gallery, I noticed a small group of businessmen in dark suits standing around a tall man towering above them. I figured that was the artist, and he noticed me. It was Kikai, and he gestured with his eyes for me to wait until he finished talking with the businessmen.

I was content to wait and meditate on his portraits and after a few minutes the crowd thinned out. Kikai came over and spoke to me in English. He was curious about my impression of his pictures.

We talked, and since it was almost closing time, he suggested we go out for coffee. We had just met, but Kikai had a relaxed and open nature that put me at ease. We ordered coffee and he asked me about my life and journeys. He also shared his own life story. We talked about many things, including India, a place that reminded him of his childhood home in the north country of Yamagata.

Meeting Hiroh Kikai was a rare experience for me. After arriving in Tokyo, I was meeting other famous Japanese photographers. Most tried to assert their vision and ego on me, but Kikai was different. He was quiet, curious, and deeply respectful of other people. I didn’t see him as a professional photographer; he was a philosopher who used his camera to make sense of our convoluted world.

A Deeper Dialogue with the World

I learned that Kikai preferred to work alone. He stayed away from the Japanese photography world, especially the cult of “me” artists, who hung out in the coffee shops and sexy bars of Shinjuku. We both recognized their raw, provocative, and sexy style as an easy formula for success, especially for a contemporary art world hungry for new exotic fetishes coming out of Asia.

The crazy course of the 20th century was something Kikai was keenly aware of. He saw how people’s eyes were becoming atrophied by the deluge of shallow and fleeting images that bombard us daily. Kikai was seeking a deeper dialogue with the world. And he found it, not in the trendy chaos of Shinjuku, but in the timeless world downtown in Asakusa.

Kikai told me that he didn’t see photography as a fine art. For him, it was a means for shedding light on hidden truths. In an interview in his book Asakusa Portraits, published by Steidl in 2008, he said: “When I photograph things or people, I want to capture not the surface qualities, but the subject’s essence. What keeps me creative is returning to the simple question, “What does it mean to be human?”

That question led him to avoid working as a professional photographer. Instead, he chose to work as a manual laborer. He drove trucks, worked at dockyards, and spent months at sea laboring on tuna fishing boats. Such experiences gave him time to think about life and develop humility and empathy for people that his insightful portrait photographs reveal.

A Celebration of Humanity

Kikai told me he chose Asakusa because it was close to where he lived. “I could easily walk over to the temple in my free time and wait for interesting characters to wander by.” When someone caught his eye, he’d engage them in conversation, and when he took their portrait, he looked to reveal their backstory.

As we drank coffee, Kikai also told me he had never studied photography formally. His philosophy teacher in college, Sadayoshi Fukuda, got him started. Fukuda encouraged him to buy a Hasselblad camera, even lent Kikai the money, and introduced him to people like Shoji Yamagishi, an influential editor. That is how he learned about the work of the American portrait photographer Diane Arbus.

While Kikai’s portraits can be compared to the darkly soulful portraits of Diane Arbus, his images were neither derivative nor sentimental. They show a positive celebration of humanity that reflects the purity of his vision. “A human being is a mysterious and strange organism,” he said.

Revealing Something Universal

When I was asked to write this article on Hiroh Kikai, I reached out to a mutual friend, Tsuyoshi Saeki. He was the publisher and editor of a profoundly beautiful magazine published between 2003 and 2015 called Kaze no Tabibito. Saeki was a dear friend of Kikai’s and cared for him until his death.

Saeki summarized Kikai’s legacy in a few words: “His mission was to reveal something universal in the soul of his subjects. We find it in his photographs, and it touches and enriches our lives in ways that inspire a deeper and more expansive dialogue with the world.”

In these times, when we no longer know what is fake or what is real, Kikai’s legacy is a reminder of what it means to be human. That is why I never tire of his images and continually return to them, just as I return to Wim Wenders’ movies. As artists, both of them are calling us to discover beauty and (deeper) meaning in our daily lives. It is a message of true abundance.

Hiroh Kikai (鬼海 弘雄, 1945-2020) is best known for four series of monochrome photographs: portraits of people in Asakusa, scenes of buildings in and around Tokyo, and rural and town life in India and Turkey. Kikai was not widely known until 2004, when the first edition of his book Persona, a collection of Asakusa portraits, won the prestigious Domon Ken award. In 2009, his book Asakusa Portraits was published by Steidl and ICP, and his work came to the attention of an international audience. In 2019, his final book Persona: the Final Chapter 2005-2018 was published by Chikumashobo.

Everett Kennedy Brown is a multi-talented American artist based in Tokyo. He writes books in Japanese, performs ancient wind music and uses an 8×10 camera and hand-made glass negatives to explore Japan’s deep culture. His innovative images are in the permanent collections of museums in Japan, Europe and the United States. In 2013 he was awarded the Japanese Government’s Cultural Affairs Agency Commissioner’s Award in recognition for his creative activities.

*All of the photographs in this article are the copyright of Hiroh Kikai and used with the permission of Kikai’s family. Reuse of the images is strictly prohibited.

Image files were kindly provided by Chikuma Shobo, and come from the book Persona: The Final Chapter 2005-2018.